Alien Land: Geographical Expansion

An excerpt of Homecoming: A Thematic Trip and the World of Activity Approach.

by Oliver Ding

My first Kindle book was released on September 7, 2025. My recent trip to Fuzhou, China, inspired it.

From late June to July 2025, I traveled to China, spending most of my time in Fuzhou, also known as Foochow. Before moving to the U.S., I had lived in Fuzhou for nearly 20 years. This journey became a deeply meaningful re-engagement with familiar places, old friends, and the memories that had shaped my earlier life.

At the beginning of the trip, I revisited Wuyi Mountain, searching for a symbolic object that had inspired my son Peiphen’s name. This moment led me to re-read my 2015 autobiography, A Freesoul.

Immersed in this rich experiential context, I began connecting the World of Activity approach with my situational experiences.

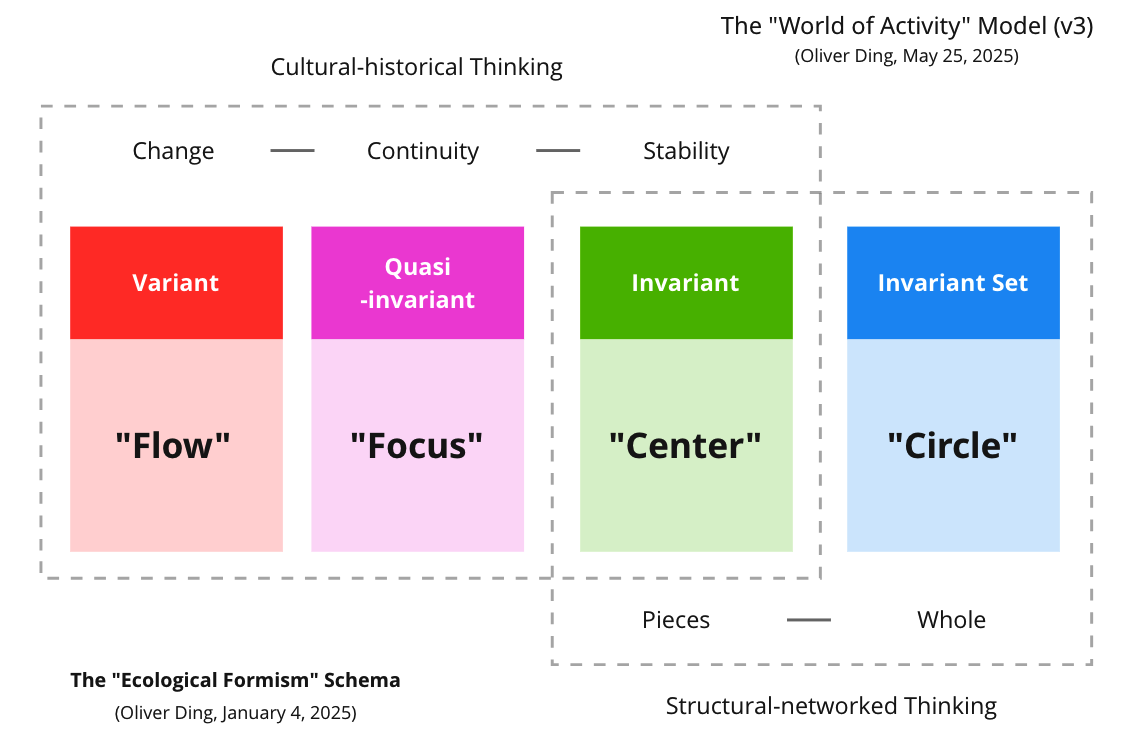

While in Fuzhou, I mainly used the World of Activity model, also known as the “Flow — Focus — Center — Circle” schema, to reflect on my 2015 autobiography.

I discovered several distinct forms of “World of Activity,” corresponding to different developmental stages of life.

- Hometown: Primordial Situatedness @ World of Activity

- Alien Land: Geographical Expansion @ World of Activity

- Domain: Professional Development @ World of Activity

- Internet: Digital Engagement @ World of Activity

- Foreign Land: Cultural Reconstruction @ World of Activity

Later, I detached my mental focus from the past and attached it to the present. When staying at Fuzhou, I had opportunities to meet with old classmates and friends. We had wonderful conversations and exciting tours around the city.

Paying attention to the present brought new insights to me. Eventually, I discovered two more forms of the World of Activity.

- Inheritance: Generative Anticipation @ World of Activity

- Homecoming: Spatio-temporal Emergence of the World of Activity

Each form represents not merely a change of location or circumstance, but a fundamental reorganization of how the World of Activity structures itself — its boundaries, centers, and internal dynamics.

I continued writing daily notes to deepen the theory-practice connection. By the end of the trip, I had written 138,352 words in Chinese. Combined with the original 2015 autobiography, the total came to nearly 211,145 words. The newest version, v2.1, is about 217,665 words.

I edited it as a new Chinese book draft titled Freesous in Fuzhou: Theme, Enterprise, and World of Activity.

Unfortunately, the original was written in Chinese. After returning to the U.S., I started rewriting it in English. The result is this English book: Homecoming: A Thematic Trip and the World of Activity Approach.

While most materials are based on my Chinese notes, the English book is not a translation of the Chinese book draft. For example, in the Chinese one, it has six parts, and I wrote notes on the World of Activity approach, and relevant ideas such as the Social Form framework, the Thematic Enterprise framework, and the Strategic Agency framework. In the English one, I focus on the trip itself and the World of Activity approach. Other topics will be explored in other future books.

Homecoming is more than a memoir. It is both a personal narrative and a theoretical contribution, showing how everyday experience can become a source of cultural insight, creative frameworks, and intergenerational connection.

Chapter 4: Alien Land: Geographical Expansion

My adolescence and the early dual-center pattern

- The Cape of Good Hope Poetry Society

- Academic Classes vs. Interest Clubs

- Surviving Center vs. Thriving Center

- Mountains, Rivers, and Flow

- Creative Engagement with Givenness

After elementary school, I moved from Pengdun to Jianyang, a small town near my childhood home. Since Jianyang is part of my early life, I will skip a detailed analysis of this period.

Later, I moved to Fuzhou to continue my higher education. I lived in Fuzhou for almost 20 years before moving to the U.S. While I used to call Fuzhou my second hometown, to highlight the geographical expansion of my World of Activity during adolescence — and the sense of entering a place both unfamiliar and larger than my previous environments — I labeled this stage as “Alien Land.”

From a small village in Pengdun to Fuzhou, the capital of Fujian Province, these moves illustrate the natural process of geographical expansion experienced by many during adolescence in a rapidly urbanizing world. Fuzhou represented a new scale, new opportunities, and a broader social landscape, marking a clear contrast with the familiarity of my earlier hometown.

The Cape of Good Hope Poetry Society

During a recent trip to Fuzhou, I went to my house, where my older sister lives, and organized old books and objects in my study. I unexpectedly came across a cassette, a poetry recital collection I had created between 1993 and 1994, featuring sixteen of my own poems. I had released nine copies in two versions. The collection was titled Crossing the River of Dream, a name inspired by the pen name I used at the time, Dream Dawn (note 1).

Alongside the cassette, I found a photograph showing the cassette and its visual design elements. The table of contents included an illustration of a person raising a sail on the sea, originally designed by a classmate as the logo of the Cape of Good Hope Poetry Society (note 2). In the photograph, there was also a finely crafted black-and-white print of a sailor sitting by a moored boat, perhaps reflecting on the tumultuous journey just completed, or imagining the voyage yet to come.

This cassette and photograph not only revived memories of my poetry from that period, but also pointed me toward an important part of my adolescent World of Activity — the Cape of Good Hope Poetry Society. In the World of Activity model, this society represents a Center, a focal point around which a set of creative activities, social interactions, and personal growth were organized.

Academic Classes vs. Interest Clubs

As life progresses, a person’s World of Activity evolves both temporally and spatially. In childhood, the World of Activity is centered around the hometown. During adolescence, particularly in the student years, this world expands geographically, creating an Alien Land that becomes the site of new centers of the World of Activity.

Two distinct centers emerge when we compare my childhood hometown and adolescent student years:

- Hometown: Pengdun (my Home + Peifeng Academy)

- Alien Land: Fuzhou (Academic Classes + the Cape of Good Hope Poetry Society)

In both periods, Focus points arise that anchor the World of Activity and later develop into explicit or implicit Centers. Peifeng Academy was an implicit center, experienced personally and through writing, not readily perceived by others. In contrast, the Cape of Good Hope Poetry Society was an explicit center, a social entity and interest club observable by peers.

The movement from Pengdun (a small village) to Jianyang (a county town), and finally to Fuzhou (the provincial capital), represents a three-stage expansion of my World of Activity. This expansion corresponds with the development of adolescence and the growth of new social and academic networks.

A typical adolescent structure in an alien land can thus be abstracted as:

Alien Land (Academic Classes + Interest Clubs)

This mirrors common experiences for many adolescents: leaving home for education, engaging in academic learning, and participating in social or interest-based clubs, which serve as critical hubs for self-exploration, peer interaction, and skill development.

Comparing childhood and adolescent periods, the basic ecological forms of the World of Activity differ slightly.

Childhood:

- Before — After: elders vs. younger generations

- Slow — Fast: the unstructured pre-school time vs. the structured demands of schooling

- Up — Down: parents vs. children

- Left — Right: siblings and playmates of the same age

- Inside — Outside: oneself vs. strangers

- Center — Periphery: home vs. the wider world

Adolescence:

- Before — After: senior students vs. junior students

- Slow — Fast: interest exploration vs. academic activities

- Up — Down: instructors vs. learners

- Left — Right: classmates and collaborators

- Inside — Outside: club members vs. wider campus peers

- Center — Periphery: interest club vs. the alien city

Through this dual-center analysis, we see that each life stage develops its own ecological forms, with overlapping but distinct structures, reflecting both continuity and expansion of the World of Activity. We should notice that the description of ecological forms is mediated by developmental stages and the local cultural background.

Surviving Center vs. Thriving Center

As mentioned in the previous discussion of my childhood, the double-center structure first appeared as Surviving and Thriving Centers in early life. We see this pattern emerge again during adolescence.

In Fuzhou, academic classes served as the Surviving Center. They provided structure, routine, and essential skills for future development. Attendance, coursework, and examinations ensured continuity in learning and met the fundamental requirements of higher education.

Meanwhile, the Cape of Good Hope Poetry Society functioned as the Thriving Center. This interest club offered a space for creativity, self-expression, and social engagement. Within the society, I explored poetry, collaborated with peers, experimented with visual design, and cultivated talents that extended beyond the formal curriculum. Its influence, while subtler than that of the Surviving Center, was profound in shaping my personal growth, social connections, and creative identity.

Together, these centers illustrate the complementary roles of Surviving and Thriving Centers within an alien land: one sustaining necessary life and academic routines, the other fostering exploration, development, and engagement. During adolescence, this dual-center pattern captures the balance between stability and opportunity, between necessity and aspiration, in an expanded World of Activity.

Mountains, Rivers, and Flow

The geographical expansion from hometown to alien land in my adolescence followed a unique pattern that would later influence my understanding of knowledge flow and creative development. Rather than a simple point-to-point movement, my journey from Pengdun to Fuzhou traced the natural course of the Min River system.

From my childhood village, I first moved to Jianyang, a county town where the Chongyang Creek (note 3) flows down from the Wuyi Mountains. This creek, carrying what I poetically described as “the lingering fragrance of rock tea and the scholarly tradition of Zhu Xi,” became my first encounter with the metaphor of flowing knowledge (note 4).

When I moved to Fuzhou for higher education, I discovered that my geographical journey followed the river’s natural course. The Chongyang Creek becomes the Jian River (note 5) as it flows through Jianyang and meets the Mayang Creek. From Nanping, it transforms into the Min River (note 6), broadening as it approaches the provincial capital, finally reaching the sea at Fuzhou.

The Rhythm of Return

During my four years of professional school, this river system became more than geography — it became the rhythm of my World of Activity expansion. Each semester, I traveled downstream from my hometown to school, following the current toward broader horizons. Each vacation, I traveled upstream, against the flow, returning to my roots.

This back-and-forth movement created what I now recognize as a foundational pattern in my understanding of knowledge flow. It was in Fuzhou that I first encountered the famous words of Lin Zexu, the renowned Qing Dynasty official and Fuzhou native: “The sea embraces all rivers; its vastness comes from its openness.” (note 7) This phrase immediately resonated with my lived experience of following the river from mountain source to ocean destination, and I adopted it as my personal motto.

Lin Zexu’s words captured something essential about my geographical and intellectual journey. Just as the Min River grows by accepting tributaries from countless mountain streams, my own World of Activity was expanding by embracing diverse influences — from the scholarly traditions of my mountain hometown to the cosmopolitan energy of the provincial capital, from the disciplined structure of academic classes to the creative freedom of the poetry society.

Min River as a Mentor

The geographic expansion from mountains to sea demonstrated how creative individuals can engage with the Environment. Rather than simply accepting geographical constraints as limitations, I found myself in creative resonance with the landscape itself.

The Min River system became more than a transportation route — it became a teacher. The concepts of upstream and downstream, knowledge inheritance and knowledge sharing, the convergence of many streams into one great flow — these ideas that would later become central to my theoretical work were first discovered through creative dialogue with the river’s natural patterns.

Creative Engagement with Givenness

As established in Chapter 2, every person’s World of Activity is fundamentally bounded by four types of givenness: Birth (the temporal beginning we find ourselves thrown into), Death (the finite temporal horizon), Language (the symbolic inheritance we discover ourselves already within), and Environment (the material conditions that confront us as facticity). These givens are not chosen but present themselves to consciousness as already-there, before our willing or choosing.

Looking back through the lens of the World of Activity model, my adolescent experience demonstrates how creative individuals can simultaneously engage with these givenness, transforming inherited constraints into creative resources:

Language Givenness through Poetry

The Chinese language and its poetic traditions presented themselves as both an inheritance and a creative medium. The Misty Poetry movement had already challenged conventional Chinese poetic expression, creating space for personal voice and experimental form. The Cape of Good Hope Poetry Society and my cassette Crossing the River of Dream represent active creative engagement with this Language givenness. Rather than passively accepting established literary conventions, we participated in transforming inherited poetic possibilities into personal artistic statements through situated learning in our community of practice.

Environment Givenness through Geographic Flow

The Min River watershed, the cultural geography of Fujian, and the urban environment of Fuzhou confronted me as material facticity. Yet this Environment givenness became a source of creative resonance rather than mere constraint. The rhythmic movement between mountain source and ocean destination, embodied in my adoption of Lin Zexu’s motto, transformed geographical boundaries into metaphorical resources for understanding knowledge flow and creative development.

This experience illustrates a crucial aspect of World of Activity development: while Environment represents one of the four givens that bind every individual’s world, creative engagement with environment can transform constraint into inspiration. The same geographical features that might limit one person’s horizons became, for me, a source of enduring metaphors and organizing principles.

My adolescent journeys along the Min River system established a pattern of seeking creative resonance with natural and cultural environments — what I now understand as an active, dialogical relationship with the Environment's givenness rather than passive acceptance of geographical boundaries.

The dual-center pattern of Academic Classes and Poetry Society in Fuzhou thus took shape within this larger flow dynamic, where mountains provided the source, rivers provided the pathway, and flow provided the unifying principle for understanding how individual development participates in larger creative currents.

Notes

- The collection was titled Crossing the River of Dream (渡梦河), a name inspired by the pen name I used at the time, Dream Dawn (梦晓).

- … the Cape of Good Hope Poetry Society (好望角诗社).

- … the Chongyang Creek (崇阳溪).

- … what I poetically described as “the lingering fragrance of rock tea and the scholarly tradition of Zhu Xi,” 从美丽的武夷山上流下的崇阳溪水,它带着岩茶的余香和朱子遗风流经我的家门。

- … the Jian River (建溪)

- … From Nanping (南平), it transforms into the Min River (闽江).

- … the famous words of Lin Zexu (林则徐), the renowned Qing Dynasty official and Fuzhou native: “The sea embraces all rivers, greatness lies in tolerance” (海纳百川,有容乃大).

v1 - 2,600 words