Appropriating Activity Theory #5: Kids are Our Teachers (2018)

Learning Theory from Life’s Earliest Explorers

This post is part of the "Appropriating Activity Theory" series, which reflects my creative journey of engaging with Activity Theory from 2015 to 2025.

by Oliver Ding

November 14, 2025

1

In 2017 and 2018, I worked on designing an iPhone app that supports one-on-one video talks. This experience inspired me to reflect on the social design of digital platforms in general. At that time, I was learning Activity Theory by reading Bonnie Nardi’s books about Activity Theory and HCI. In fact, the focus of her books is mainly on two accounts of Activity Theory: A. N. Leontiev’s Activity Theory and Yrjö Engeström’s Activity System model. I tried to apply these accounts to explain digital one-on-one interpersonal social practice; however, I found the results were not as ideal as I had expected.

I then realized I needed an approach that takes intersubjectivity as its level of analysis. I started reading more papers about Activity Theory and CHAT in general, and finally, I found a level of analysis called Joint artifact-mediated activity. According to Andy Blunden (2009), “Michael Cole (2000) reads Vygotsky’s unit of analysis for psychology as ‘joint artifact mediated activity.’ Following Vygotsky, Cole does not make a distinction between ‘action’ and ‘activity’. Absent the specialized meaning given to ‘activity’ as opposed to ‘action’ by Leontyev, this is not an issue of principle. For his own work, Cole extends this unit of analysis to ‘joint, mediated, activity in context’.”(2009)

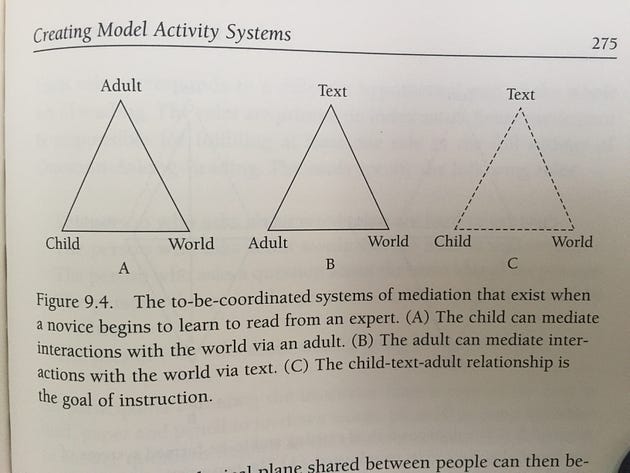

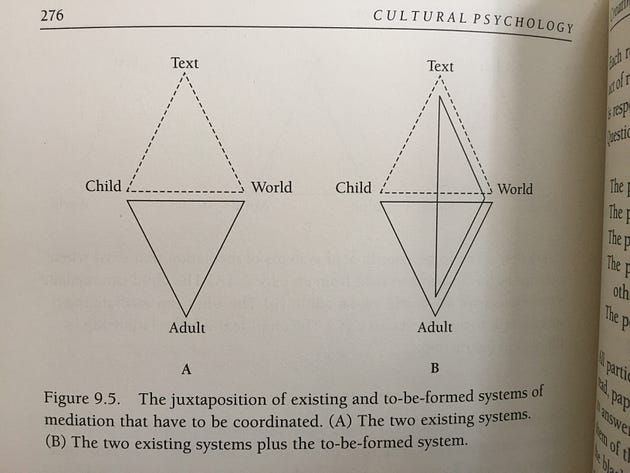

I also found an exemplar of empirical research in Michael Cole’s book Cultural Psychology. The study focused on the diagnosis and remediation of children’s reading difficulties as part of a single system of activity. Cole and his colleagues believed that reading is a developmental process and that the goal of reading instruction is to provide children with the means to reorganize their interpretive activity using print. They developed a model to represent their conception. One of their diagrams is shown below (Source: Michael Cole, 1996, p.275).

According to Cole, “… the given and to-be-developed systems of child mediation are juxtaposed and the given adult system is then superimposed, to reveal the skeletal structure of an ‘interpsychological’ system of mediation that, indirectly, establishes a duel system for the child, which permits the coordination of text-based and prior-world-knowledge-based information of the kind involved in the whole act of reading.” (1996, p.275) The following diagram is the final model.

At that moment, I realized it was possible to design new models using theoretical concepts drawn from the Vygotskian tradition. That marked a dramatic turning point in my process of appropriating Activity Theory, CHAT, and Vygotsky’s ideas.

Moreover, the emotional encouragement I received from reading Michael Cole’s work accelerated the development of many activity-centered knowledge frameworks I created later.

2

In 2018, another significant theoretical source was Roger Barker’s Behavior Settings Theory, which Cole also mentions. Discovering this inspired me to explore the direct connection between Vygotsky and Barker in the development of Activity Theory and CHAT.

Cole aimed to bridge Cultural-Historical Psychology and American Anthropology. As a student of Alexander R. Luria, one of the founders of Cultural-Historical Psychology and a leader of the Vygotsky Circle, Cole focused on studying the role of culture in the mental life of human beings and developed Cultural Psychology. He did not simply adopt all ideas from Vygotsky and others; as he wrote, “I could not simply embrace the form of cultural psychology that the Russians offered. On the basis of my own research. I rejected their inferences about cultural differences and was skeptical of their broad conclusions concerning the cognitive impact of writing and schooling. Over time, however, I began to see ways to combine key insights and methods of the cultural-historical approach with equally important insights and methods from American approaches.” (p.107)

Cole echoes Barker’s ideas in his 1996 book Cultural Psychology, particularly regarding “Context/Practice/Activity and Ecological World Views,” encouraging readers to consider ecological psychologists’ perspectives. He notes the affinities between these views:

There are important affinities between the various views about a supra-individual unit of analysis associated with the notions of context, practice, activity, and so on, and the views of those who identify themselves as ecological psychologists (Altman and Rogoff, 1987). These affinities grow out of a common starting point, the ecology of everyday human activities, and are evident in the proclivity of researchers of both views to conduct their research in naturally occurring social settings rather than experimental laboratories. These affinities can also be seen in the appearance of the metaphor of weaving in the writings of both groups. The following example is taken from the work of the pioneer ecological-developmental psychologists Roger Barker and Herbert Wright, who were attempting to characterize the relation of ecological setting to psychological processes.” (1996, pp. 141–142)

There is also an indirect connection between Cultural-Historical psychologist Lev Vygotsky and Ecological Psychologist Roger G. Barker via Kurt Lewin, Barker’s teacher. According to Yasnitsky (2019), “…the notion of ‘zone’ migrated into Vygotsky’s work from his contemporary German American scholar Kurt Lewin (1890–1947)… Lewin’s considerable influence on Vygotsky in the last two or three years of the latter’s life is well documented.”

Bark Rogers’ work is supported by the legacy of his teacher Kurt Lewin. According to Heft, “Lewin (1946/1951c) conceptualized behavior as being a function of the constellation of factors present in the phenomenal field (i.e., the life space) at a particular time. It is this multifactor psychological environment as experienced by the person that is critical, according to Lewin, for an analysis of behavior. Lewin also recognized that environmental features outside of the individual’s life space at a particular time, comprising what he called the ‘ecological environment,’ have significant, if indirect, effects on behavior. In his view, these so-called ‘nonpsychological’ factors residing beyond the life space have their origins in physical environmental conditions and sociocultural processes. ”(2001, pp.247–248)

Lewin also used the term “psychological ecology” to describe these “nonpsychological” factors. Unfortunately, he didn’t complete this project. Roger Barker and his colleague Herbert Wright, also a Lewin postdoctoral fellow, continued the work and eventually developed Behavior Settings Theory.

In Behavior Settings (1968, 1989), Barker defined behavior settings as including physical environment and standing patterns of behavior, in which interdependence among elements is stronger than with elements outside the setting. His early fieldwork with Herbert Wright, including One Boy’s Day (1951) and Midwest and Its Children (1955), documented these principles, which were later systematized in his books.

So, what is the core of the Behavior Settings theory?

According to Barker, “A behavior setting is defined in terms of two kinds of properties: structural and dynamic. On the structural side, a behavior setting consists of one or more standing patterns of behavior-and-milieu, with the milieu circumjacent and synomorphic to the behavior. On the dynamic side, the behavior-milieu parts of a behavior setting — that is, the synomorphs that comprise the setting — have a specified degree of interdependence among themselves that is greater than their interdependence with parts of other behavior settings. These are the essential properties of a behavior setting.” (1989, p.30)

In 2018, I was very excited to discover a connection between Activity Theory and Ecological Psychology. At that time, I engaged deeply with both theoretical approaches. Later, running a creative dialogue between these two lines became an obvious pattern in my creative journey.

3

In April 2018, I completed my first well-developed theoretical model of intersubjective interaction from an ecological perspective: the Ecological Zone Framework. Later, in 2020, while drafting my book After Affordance: The Ecological Approach to Human Action, I incorporated this framework into the Infoniche Framework as a unit of analysis.

Gibson’s Affordance Theory operates at the animal-environment analytical level, while Barker’s Behavior Settings Theory addresses higher-order, extra-individual social activity. However, the concept of Behavior Settings is defined as a combination of a social program and a physical place. This leaves space for developing a new analytical level—one that is not restricted by physical location.

The term Ecological Zone refers to an interactive space between two subjects engaged in a shared activity of short or long duration.

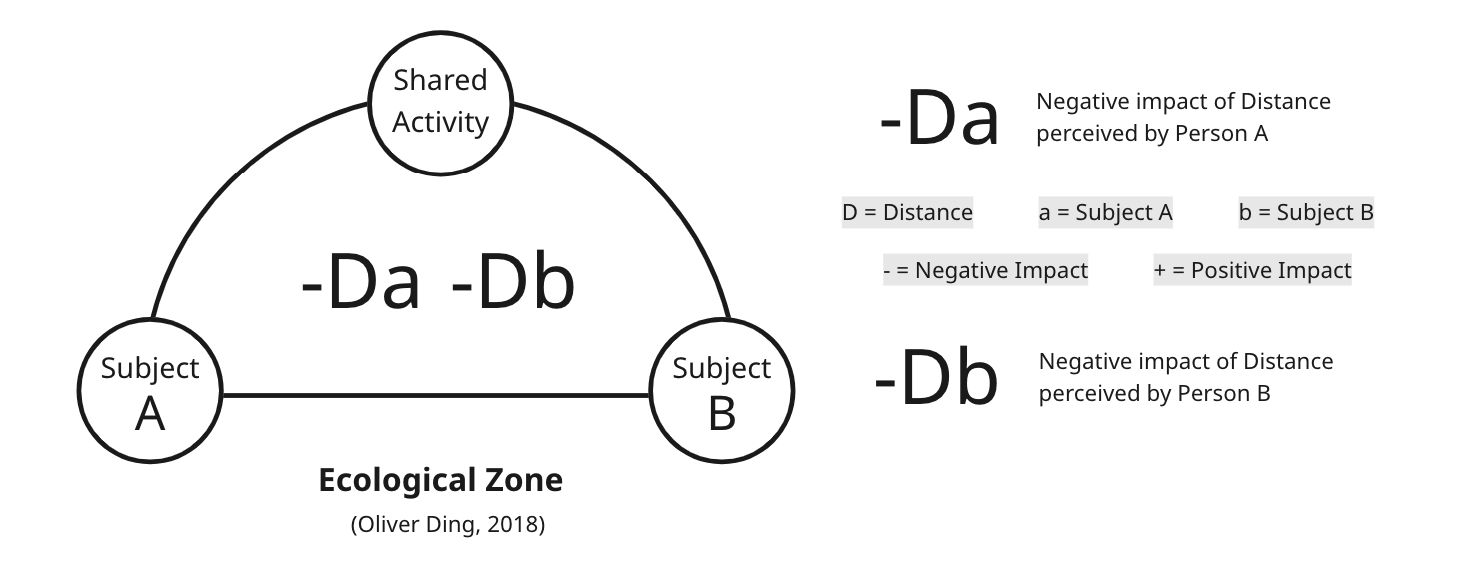

The basic model of the Ecological Zone Framework represents a dyadic structure.

This model does not provide a conventional account of intersubjectivity, as my focus is on ecological aspects. My goal is to introduce a layer bridging Gibson's Affordance Theory and Barker's Behavior Settings Theory, drawing also on Gibson's idea of the Ecological Self.

The Ecological Zone framework is also inspired by Michael Cole’s level of analysis: Joint artifact-mediated activity. The Shared Activity in the Ecological Zone framework can be understood as a form of Joint Activity. While the Ecological Zone diagram does not prominently emphasize artifacts, the framework’s Settings encompass artifacts, the environment, and the social context of shared activity, reflecting Cole’s emphasis on artifacts as well as ecological and cultural contexts.

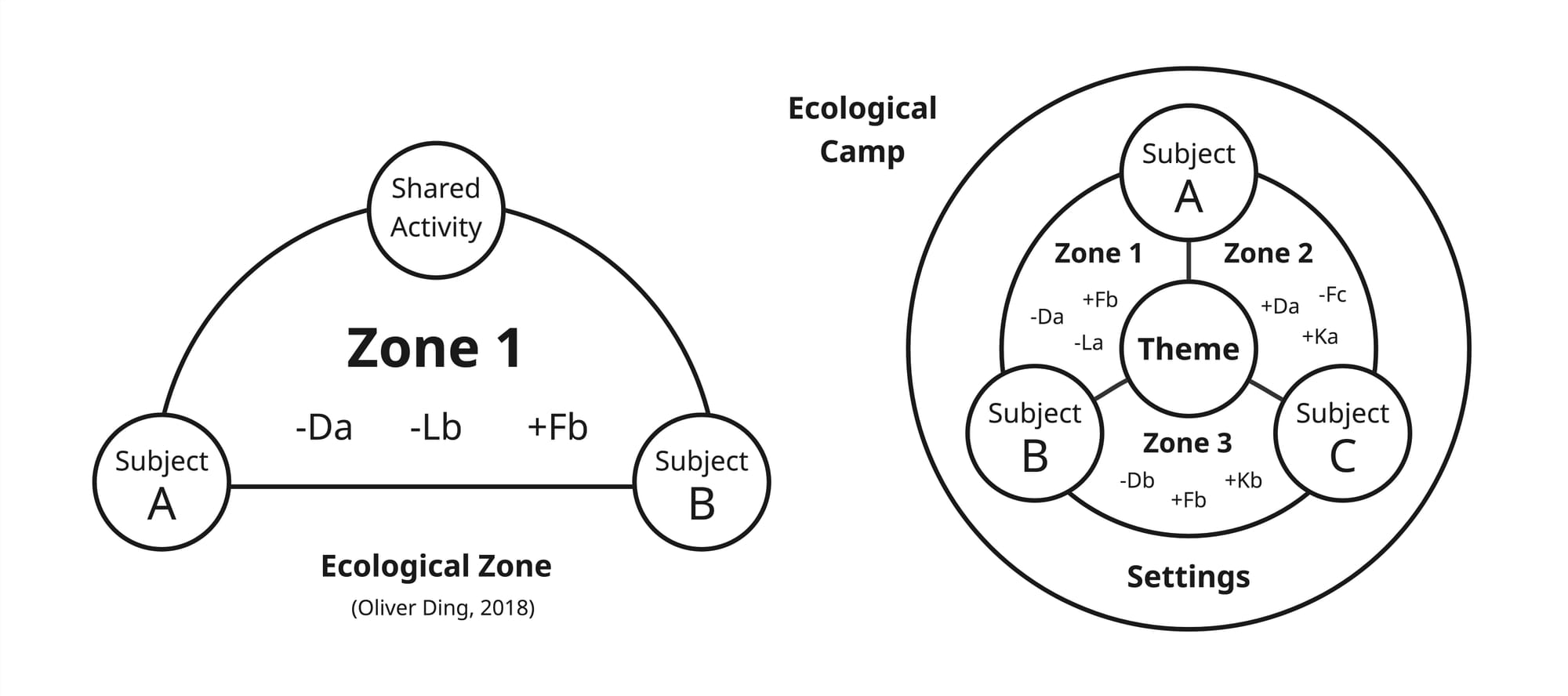

Although a ZONE is the basic unit, I typically use at least three ZONEs together for concrete analysis, because one ZONE often serves as the environment for another. Therefore, the standard model of the Ecological Zone framework is the “Tripartness” version, also referred to as the Ecological Camp. See the right diagram in the figure below.

One key ecological aspect of the framework is Ecological Force. The term "Force" is inspired by Lewin's topological psychology; however, my use of Ecological Force emphasizes the source of the force itself. I focus on the ecological origin rather than individual perception. For example, consider Distance as an ecological force:

- -Da: Negative impact of Distance perceived by Person A

- -Db: Negative impact of Distance perceived by Person B

Here, D refers to Distance, which is considered an ecological force in the context of the Ecological Zone. Distance exists as a fact between two people; if only one person is present, there is no Distance. The existence of Distance depends not on either person individually, but on their relative positions.

Suppose the shared activity is a remote work project in which Distance is a significant ecological force. Person A perceives a negative impact from this Distance, represented by the sign "-Da." Similarly, "-Db" represents a negative impact perceived by Person B.

Individual differences may result in Person B perceiving a positive impact from the same Distance. Moreover, Distance is only one type of ecological force; different activities involve various ecological forces.

While I have employed the Zone-level analysis in various other projects, the Camp-level analysis method more profoundly demonstrates what distinguishes the ecological perspective from other intersubjective analytical frameworks. The Camp level reveals how multiple dyadic relationships interact within a shared context, allowing us to examine not just isolated pairs but the dynamic interplay among three or more subjects.

There are four key concepts for understanding a Camp:

- Structural Distinctions: Since the three subjects each have their own identities, positions, and motivations, structural distinctions exist between the three Zones.

- Situational Dynamics: Individual differences among members of each Zone shape interactions. Real interactions occur between real people, giving rise to situational dynamics within each Zone.

- Themes of Practice: To curate diverse experiences of daily interactions, I adopt this concept from Curativity Theory. A Theme of Practice refers to a set of interactions sharing a common issue, agenda, or theme.

- Boundaryless Echoes: Each subject experiences each Zone differently, with experiences that may be positive or negative. To cope with negative experiences in one Zone, a subject can draw on positive experiences from other Zones or curate interactions from different Zones with similar Themes of Practice.

Originally, I named my framework the Social Zone. Later, to emphasize its ecological perspective, I renamed it the Ecological Zone.

4

In a recently published article, The Ecological Camp Framework (2018), I present three case studies that demonstrate the framework's analytical power across different contexts: family interactions during travel, digital platform dynamics, and educational settings during crisis.

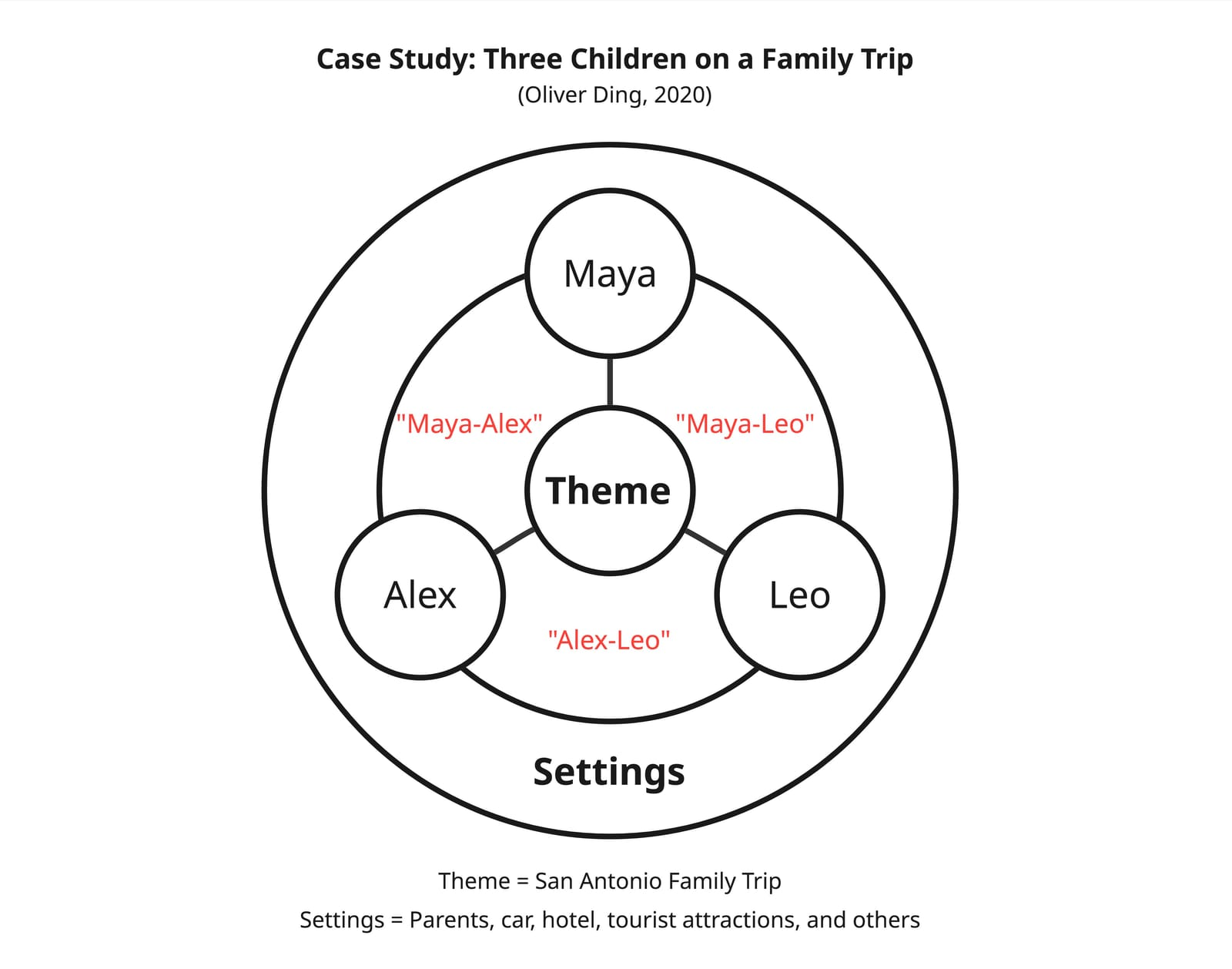

Let’s take a closer look at the first case study, centered on three children on a family trip.

In summer 2019, my young nephew and mother-in-law came to the United States for a visit. In early July, we left Houston for a trip to San Antonio. We rented a car for six people: my wife and I, our two children, plus two guests—the nephew and mother-in-law.

Note: To protect the children's privacy, I use pseudonyms throughout this case study. Our two children are six-year-old Leo and eight-year-old Alex. The nephew from mainland China is nine-year-old Maya.

In the diagram, the three subjects are Maya, Alex, and Leo. The Theme of Practice is "San Antonio Family Trip." The background Settings include parents, car, hotel, tourist attractions, and others.

In this diagram, there are three Zones: "Maya-Alex," "Maya-Leo," and "Alex-Leo." Everything that happened among these three Zones during the entire "San Antonio Family Trip" can be represented in the diagram.

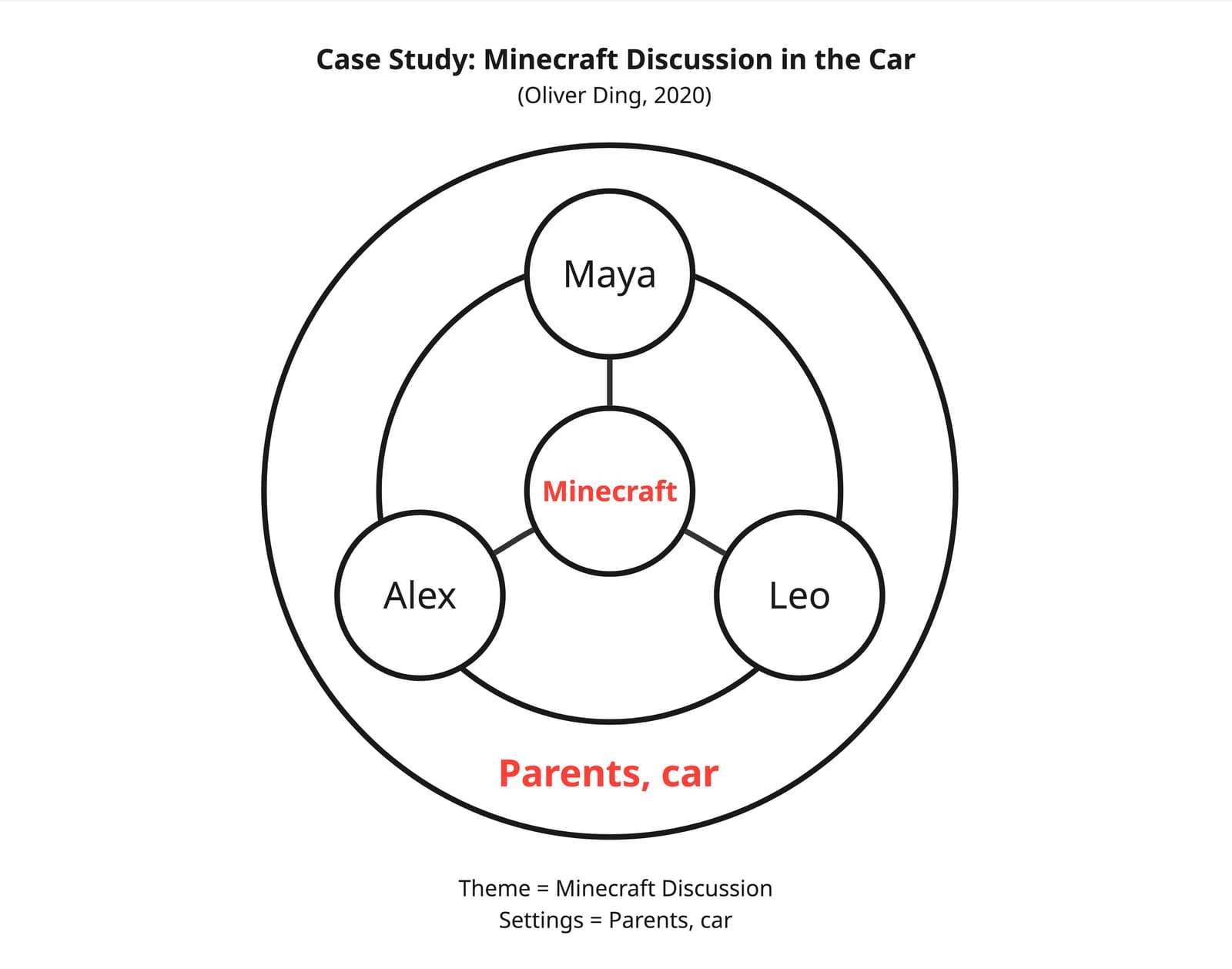

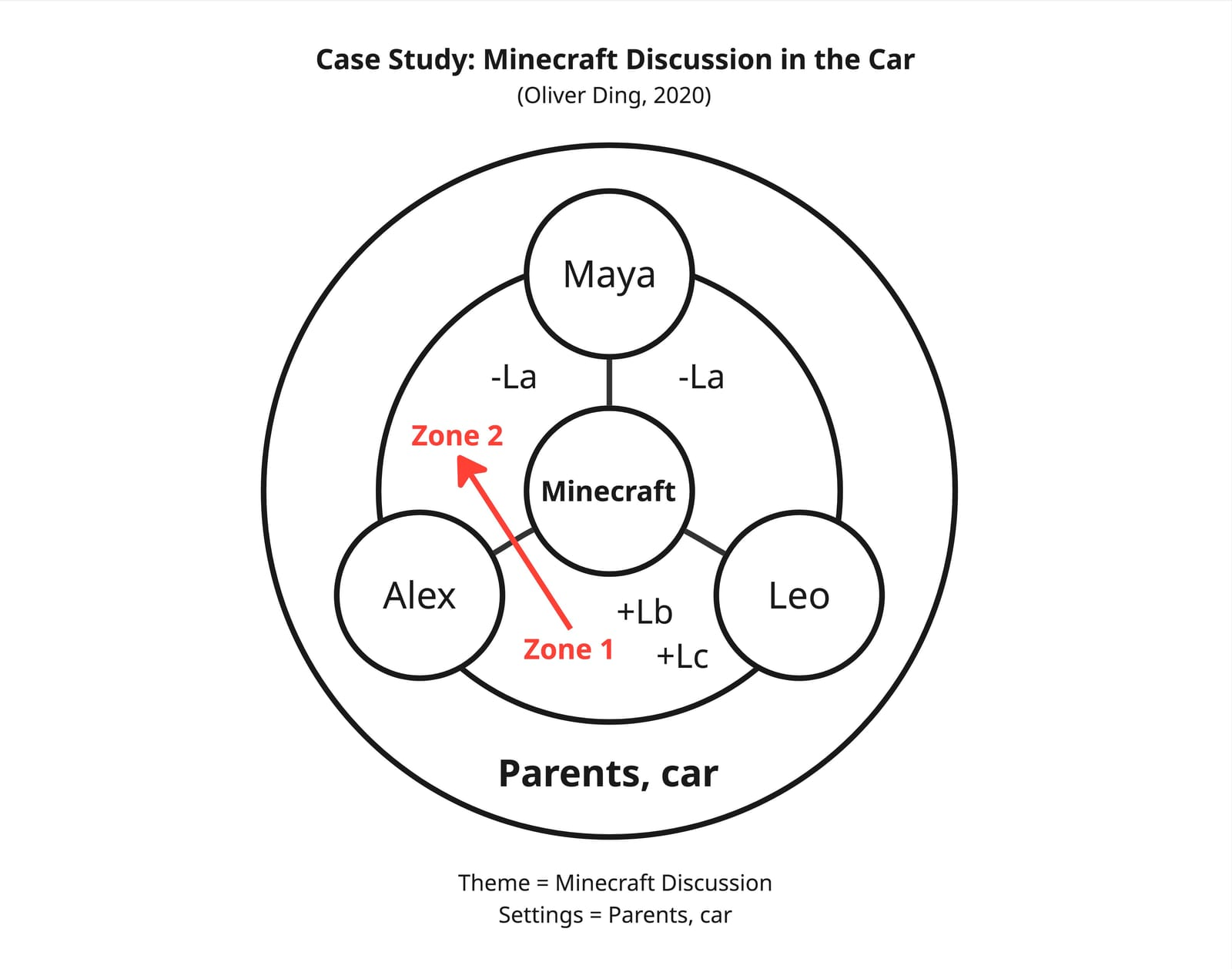

For specific single events, this diagram can also be used for in-depth analysis. For example, during the entire "San Antonio Family Trip," these three children did one thing: they discussed the Minecraft game while riding in the car. I drew a new Camp diagram specifically for this event.

The drive between Houston and San Antonio takes three and a half hours. On the way from Houston to San Antonio, Alex and Leo conversed in English about Minecraft the entire time. Maya couldn't understand what they were saying and felt anxious on the sidelines. On the return trip from San Antonio to Houston, Maya requested to join the discussion, so Alex switched to Chinese to communicate with him. The conversational subjects became Maya and Alex.

In this discussion case, the background Settings are simplified to "parents, car."

The diagram above adds some symbols to the previous one: Zone 1, Zone 2, -La, +Lb, +Lc. What do these symbols mean?

According to previous symbol explanations:

- Zone 1 represents the Zone between "Alex-Leo"

- Zone 2 represents the Zone between "Maya-Alex"

The three subjects are coded as a, b, and c, which in this case are: a=Maya, b=Alex, c=Leo

- L represents Language as a "Force"

- -La represents the negative experience that the Force of language brings to Maya

- +Lb represents the positive experience that the Force of language brings to Alex

- +Lc represents the positive experience that the Force of language brings to Leo

The diagram marks with red arrows the direction of movement from Zone 1 to Zone 2. In this case, the focus on the outbound journey was on Zone 1, with most conversations occurring in the "Alex-Leo" Zone, where they discussed Minecraft in English. Maya, due to insufficient English proficiency, was affected by the Force of language, resulting in a negative experience (-La). In fact, Maya was quite familiar with and knowledgeable about Minecraft, possessing the knowledge foundation to participate in the discussion.

On the return trip, Maya requested to discuss Minecraft in Chinese. Alex accepted this proposal and switched to discussing Minecraft with Maya in Chinese. At this point, the focus of the return trip shifted to Zone 2, the "Maya-Alex" Zone. By requesting a language change, Maya eliminated the negative impact of the language Force. His knowledge and skills about Minecraft as a Force brought him positive influence. Meanwhile, as Alex's attention shifted to Zone 2, his investment in Zone 1 was no longer as high, and Leo consequently faded from the entire conversation, turning instead to reading books and doing other things on his own.

Interestingly, this story resonates with the research of Cole and Barker on children conducted many years ago.

v1 - November 14, 2025 - 2,680 words