Cultural Frameworks: A Canvas for Reflection and Innovation

Introducing the Frame-for-Work Canvas

by Oliver Ding

From late June to July 2025, I traveled to China, spending most of my time in Fuzhou, also known as Foochow. Before moving to the U.S., I had lived in Fuzhou for nearly 20 years. This journey became a deeply meaningful re-engagement with familiar places, old friends, and the memories that had shaped my earlier life.

At the beginning of the trip, I revisited Wuyi Mountain, searching for a symbolic object that had inspired my son Peiphen’s name. This moment led me to re-read my 2015 autobiography, A Freesoul.

More specifically, I reunited with an old friend from Beijing, and together we explored the city. One of my classmates served as our guide. In this process, I rediscovered his deep knowledge of local culture and his refined character.

Immersed in this rich experiential context, I began connecting the World of Activity approach with my situational experiences. While in Fuzhou, I mainly used the World of Activity model, also known as the “Flow — Focus — Center — Circle” schema, to reflect on my 2015 autobiography. I discovered several distinct forms of “World of Activity,” corresponding to different developmental stages of life.

I began writing notes on the first day of my trip. On July 12, I curated these early notes and wrote a long post outlining a new book. The project was planned in six parts, as follows:

- Part 1: The World of Activity Approach

- Part 2: The World of Activity Analysis Method

- Part 3: Evolving Worlds of Activity

- Part 4: Evolving Social Forms

- Part 5: Evolving Thematic Enterprises

- Part 6: Strategic Agency and the Flower of Heart-Mind

The second half of the book focuses not directly on the World of Activity itself, but on phenomena occurring within or related to it. Part 4 (Evolving Social Forms) was inspired by three social forms I discovered in my biography. Part 5 (Evolving Thematic Enterprises) emerged from encounters with thematic objects during the trip and conversations with friends. Part 6 covers nine aspects of strategic agency, essential for mastering the complexity of the World of Activity.

Later, I wrote a book in English titled Homecoming: A Thematic Trip and the World of Activity Approach. By weaving life narrative, theoretical exploration, and cultural reflection, the book offers readers a unique lens to explore their own life trajectories and recognize patterns of personal and social development.

This article continues my exploration of cultural reflection and the Thematic Enterprise framework, particularly introducing a tool called the Frame-for-Work Canvas.

Contents

Cultural Reflection

The Frame-for-Work Canvas

The “Ideation — Validation — Application — Reflection” Schema

The "Milieu — Mediator — Method — Mastery" Schema

Theory, Practice, and Perspectives

The IDEATION Thematic Area

The VALIDATION Thematic Area

The APPLICATION Thematic Area

The REFLECTION Thematic Area

Cultural Frameworks as Concept Systems

Cultural Reflection

One day, while I was staying in Fuzhou, I went to a hair salon for a haircut. I was surprised that the owner used old American license plates as decoration. More interestingly, these plates featured cultural themes such as "LV 1854,""Che 726," and "BUS 1956."

The "LV 1854" theme refers to the historical development of Las Vegas. According to Google's AI Overview, "In 1854, a fort was constructed in the Las Vegas Valley by thirty Mormon settlers led by President William Bringhurst. This fort was a significant early settlement, with the settlers arriving the following year (1855) to establish the community with the help of the local Paiute population."

However, according to the website of the Nevada State Park, "In June of 1855, thirty Mormon settlers led by President William Bringhurst arrived at the meadows and with the assistance of the local Paiute population began construction of a fort structure along the creek. "

One source dates the fort to 1854, while the Nevada State Park website dates it to June 1855. It seems that the number should be 1855, not 1854. Maybe the maker of the plate did not know this historical detail.

The "Che 726" refers to the 26th of July Movement, which was a Cuban vanguard revolutionary organization. Che Guevara was one of the leaders of the organization. However, the "Che 726" is not the official logo of the movement. The official logo, which is officially written as M-26-7, is shown below.

According to Google's AI Overview, the "CHE 726" theme refers to various novelty items, most commonly a vintage-style metal tin sign or license plate featuring an image or text related to Che Guevara, designed for home, bar, or restaurant decor. It also appears as a product identifier (internal number) for a leopard jasper cheetah figurine on eBay.

The "BUS 1956" theme refers to London's iconic big red bus. According to Google's AI Overview, "In 1956, London saw the AEC Routemaster bus enter public service for the first time, with the first bus going into service on February 8. The Routemaster, a highly recognizable red double-decker bus, was designed in the late 1940s and became a beloved symbol of London until its retirement in 2005."

What really strikes me is how the shop owner put these license plates right on his drawers - drawers he opens many times every day. I can't help but wonder how that daily contact affects him over time.

When I was traveling in Fuzhou, I was sorting through old stuff back home and came up with this idea of "thematic objects." I expanded it to include "thematic places" and "thematic social networks," eventually building what I call the Thematic Enterprise Framework. I use it to make sense of how culture develops. For this barber, these license plates aren't just decorations - they're thematic objects that show how these different themes connect to his own life course.

In Chapter 7 of Homecoming: A Thematic Trip and the World of Activity Approach, I introduced three ways of cultural reconstruction.

Drawing inspiration from Hegel’s concept theory — which interprets concepts through three aspects: universal, particular, and individual — I approach the notion of Culture at three levels to understand Cultural Reconstruction:

- Universal: Broad cultural traditions, such as Confucian relational culture in China or the individualistic culture of the United States.

- Particular: Group-level cultures, exemplified by movements like free culture, which originated from open-source programming communities.

- Individual: Personal beliefs, values, and character as expressed through one’s life trajectory. For instance, during this period, the theme of Curation Commons became a defining theme of my individual cultural engagement.

If we apply this approach to the owner's life course, then these license plates represent universal themes —these three themes are popular cultural icons – concept objects in his daily life.

Each time he opens those drawers, he's not just accessing tools - he's engaging with these universal cultural meanings at the most personal, individual level. It's like a daily ritual of cultural aspiration or identity reinforcement. He has essentially created his own thematic place where these diverse cultural currents converge in his everyday work life. It's "Tiny Culture" in action - showing how global themes get localized and personalized through the simple act of choosing what objects to live with daily.

The Frame-for-Work Canvas

After returning to the U.S., I continued developing the Thematic Enterprise Framework and related models on Cultural Frameworks. In the following sections, I'd like to introduce one of these creations.

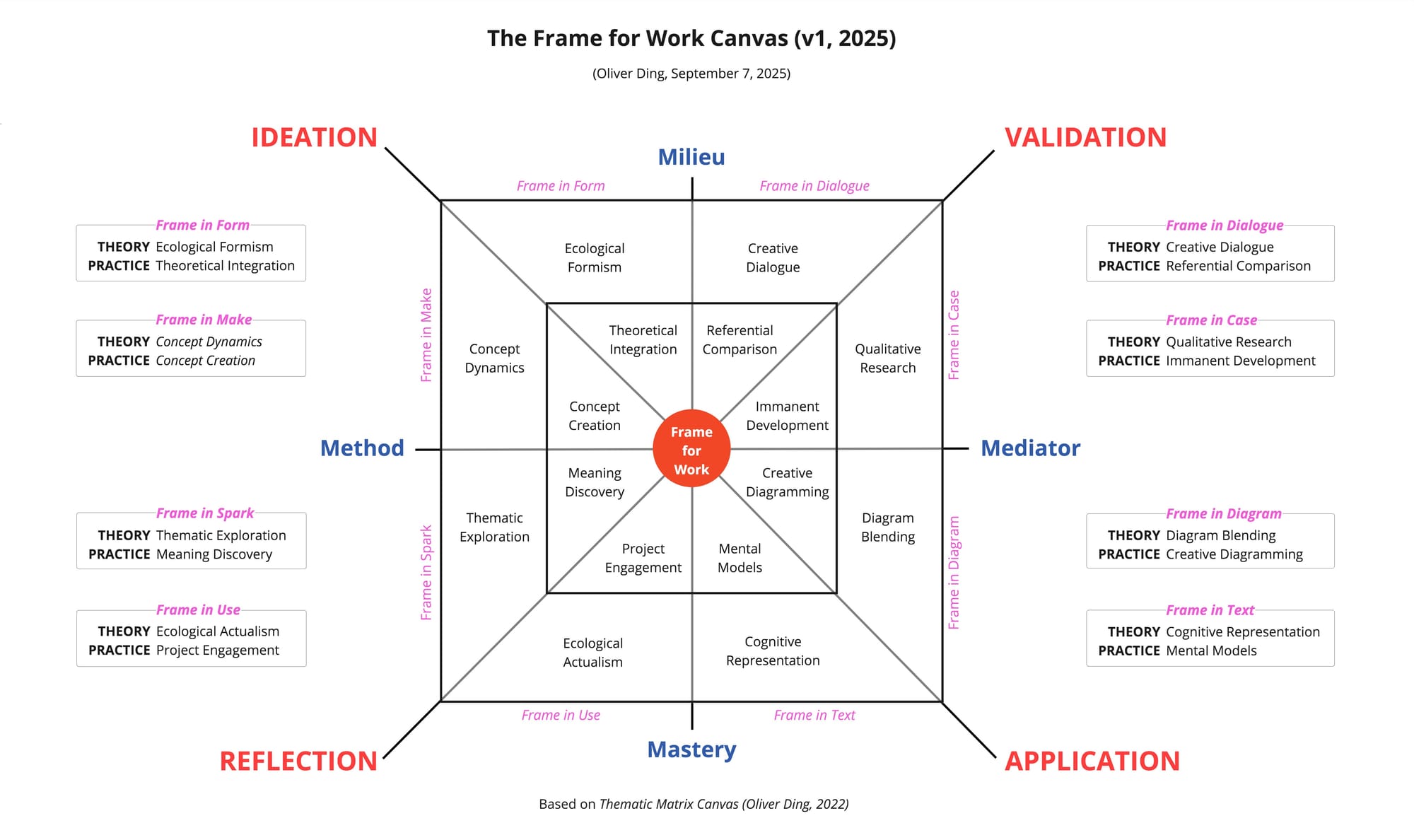

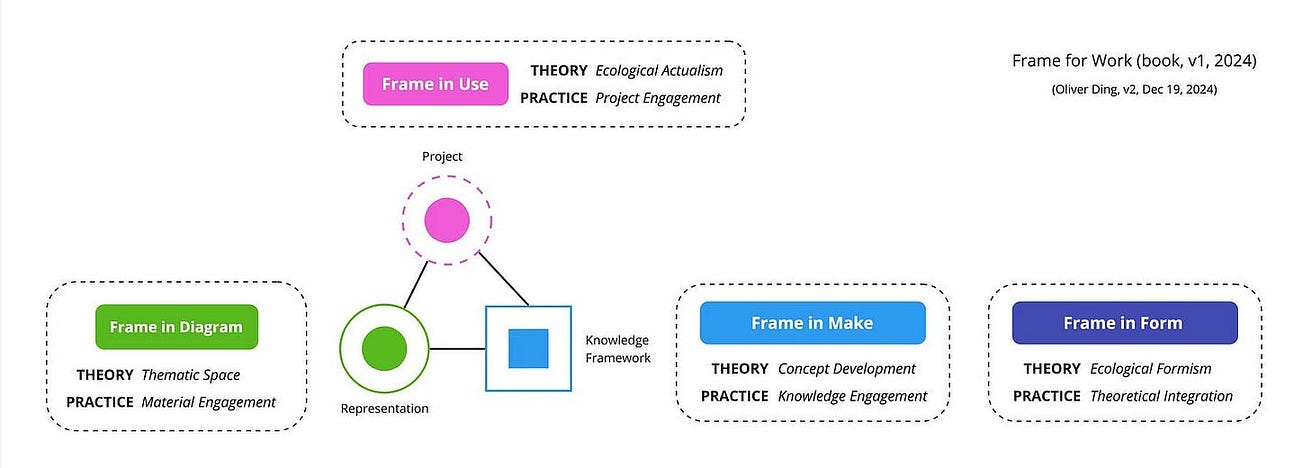

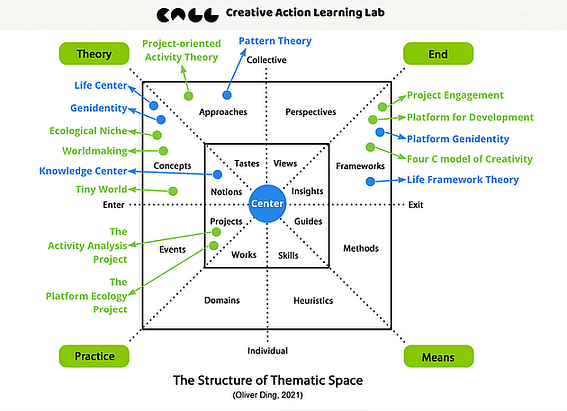

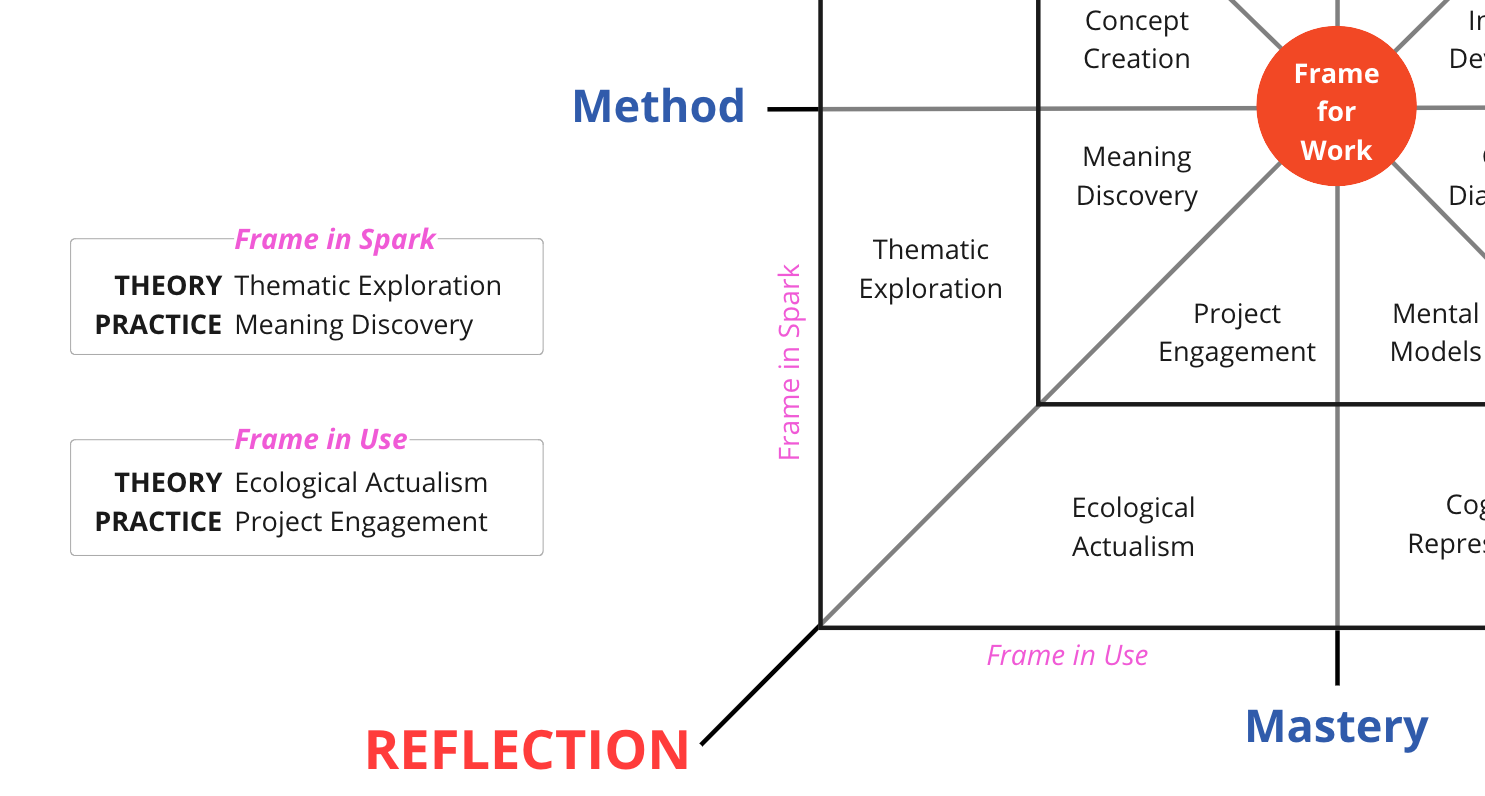

The diagram above is the outcome of a tiny knowledge curation project. Based on the Thematic Matrix Canvas I created in 2022, I reflected on four perspectives presented in my 2024 book draft, Frame for Work: Knowledge Frameworks, Predictive Models, and World of Activity, and connected these perspectives with my newest ideas.

The new canvas goes beyond the original focus of the 2024 book — Knowledge Frameworks — and extends the metaphor of the “Frame” to a broader object: Cultural Frameworks. This expansion aligns with my shift from Knowledge Engagement to Cultural Innovation, a key transition I made in late 2024 and early 2025.

The canvas curates the following knowledge elements:

- The Ideation — Validation — Application — Reflection Schema

- The Milieu — Mediator — Method — Mastery Schema

- The eight perspectives of the Frame for Work

- A set of THEORY (located in the Outer Space)

- A set of PRACTICE (located in the Inner Space)

The Thematic Matrix Canvas was originally developed as a meta-canvas in early 2022. Over the past few years, I have used it to generate a series of canvases and applied them in numerous knowledge projects.

The content of THEORY and PRACTICE refers to my own creations, with details available in the book drafts I have written and edited over the past several years.

The “Ideation — Validation — Application — Reflection” schema was born when I stayed in Fuzhou.

The “Ideation — Validation — Application — Reflection” schema

In Homecoming: A Thematic Trip and the World of Activity, I introduced a special form of World of Activity: Internet: Digital Engagement @ World of Activity.

Through this case study, I identified a deep structure underlying the dynamic development of Worlds of Activity. This higher-order structure, which I call Significant Social Forms, represents social forms that organize and contain diverse types of behavior. One such social form relates to sociotech development, which I call the Sociotech Landscape.

The Sociotech Landscape encompasses four layers:

Technology — Application — Behavior — Culture

- Underlying Technology — the underlying technical infrastructure

- Application tools — platforms, software, and utilities that leverage the technology

- Behavioral patterns — the ways individuals and groups interact with and through these tools

- Sociotech culture — the norms, values, and collaborative practices emerging around these technologies

The rise, development, and diffusion of emerging technology-driven sociotech infrastructures require a period of exploration, trial-and-error, and normalization across these four layers.

The “Technology — Application — Behavior — Culture” schema inspired me to think about other Significant Social Forms.

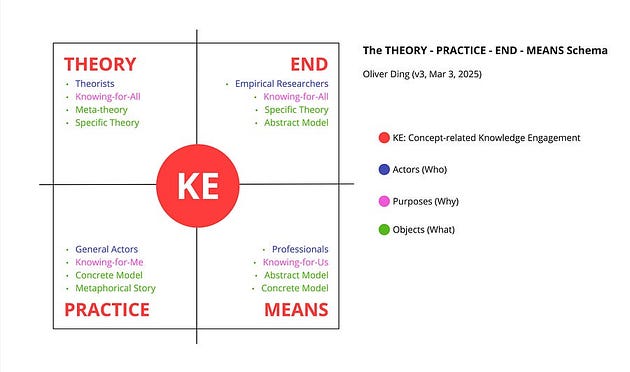

After reflecting on my work on the Knowledge Discovery Canvas, which is guided by the “Theory-Practice-End-Means” schema, I proposed a new schema for a Significant Social Form of Cultural Development: the “Ideation — Validation — Application — Reflection” schema.

There is a deep mapping between the “Theory-Practice-End-Means” schema and the “Ideation — Validation — Application — Reflection” schema:

- THEORY ↔ IDENTION

- END ↔ VALIDATION

- MEANS ↔ APPLICATION

- PRACTICE ↔ REFLECTION

Since the Knowledge Discovery Canvas was guided by the “Theory-Practice-End-Means” schema, it became possible to develop a similar canvas based on the “Ideation — Validation — Application — Reflection” schema.

However, I didn’t focus on creating a canvas around the “Ideation–Validation–Application–Reflection” schema during my stay in Fuzhou, as it was not my primary task at the time.

The "Milieu — Mediator — Method — Mastery" Schema

At the end of July, I returned to the U.S. and began writing an English book about my trip to Fuzhou and the World of Activity approach.

At the same time, I started reading Clay Spinuzzi’s new book on making the CHAT (Cultural-Historical Activity Theory): Triangles and Tribulations.

From July 31 to the present, we have had a wonderful private email conversation discussing topics relevant to the book.

Spinuzzi employs a method based on the sociology of translation, also known as actor-network theory (ANT), to examine the historical evolution of CHAT as a theoretical framework and its practical applications across various domains. While reading, I realized that this method could go beyond the CHAT case, offering potential for studying other knowledge enterprises.

In his detailed translation analysis, Spinuzzi uses the following categories of translations:

- Empirical Focus: In its studies, what scope of human interaction did CHAT investigate? What methods did researchers draw upon to adequately examine that scope of interaction?

- Mastery: What were human beings portrayed as mastering within that scope? How was human agency portrayed?

- Mediators: What means were human beings portrayed as using in their attempts at mastery? What means were theorized and investigated?

In our conversation, Spinuzzi explained that these three categories are not original to the sociology of translation but were developed by him to address aspects specific to the CHAT case.

These categories inspired me to develop the “Milieu–Mediator–Method–Mastery” schema for the Frame for Work project. I chose the term Milieu to replace the original term Empirical Focus, in order to cover a broader range of applications beyond empirical research. I also added Method to create a conceptual link between Mastery and Mediators.

So far, the “Milieu–Mediator–Method–Mastery” schema has proven to be an effective framework for discussing the issues that the Frame for Work project focuses on.

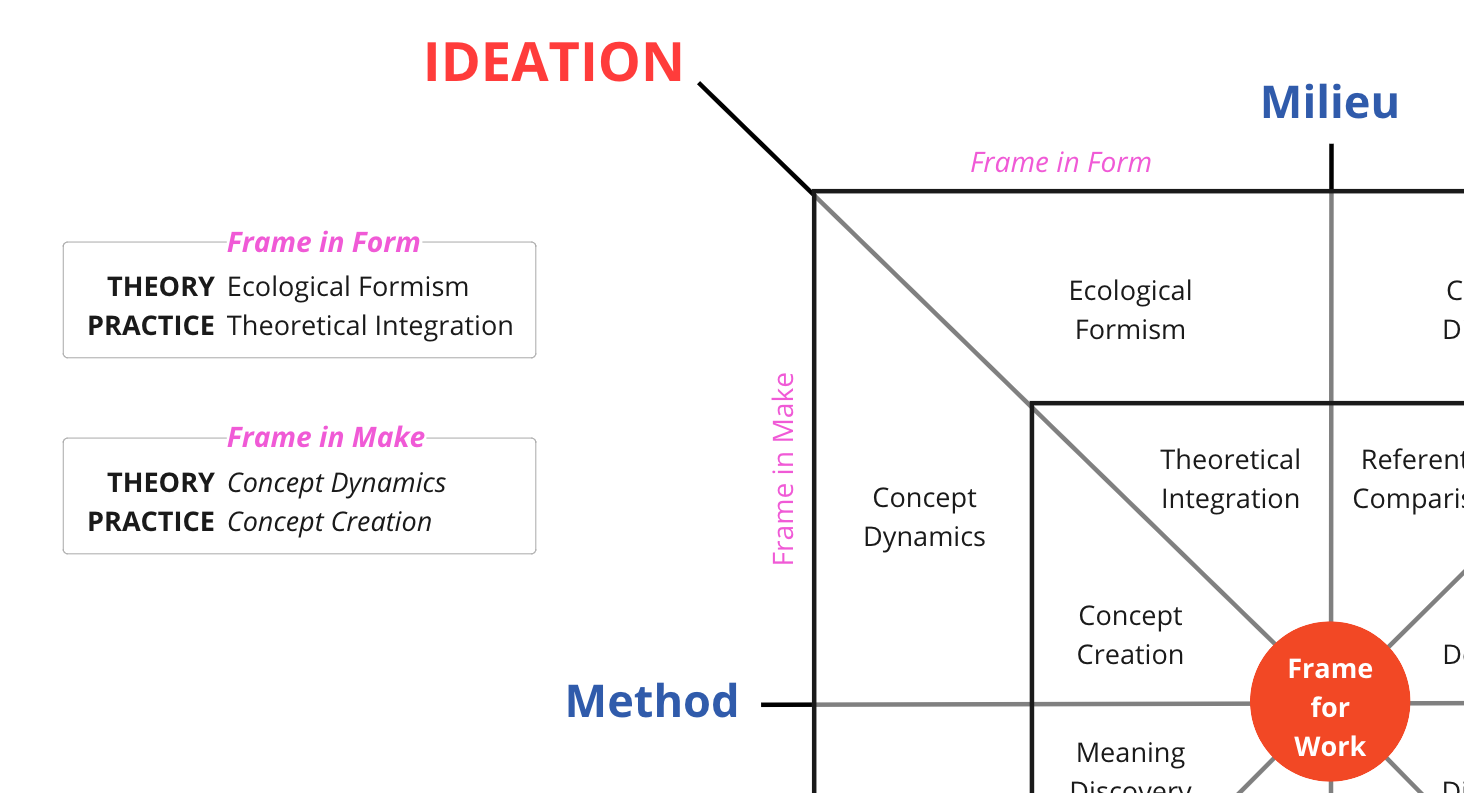

However, in my 2024 book draft, Frame for Work, I introduced four perspectives. See the diagram below.

The Frame-in-Make perspective focuses on building brand-new knowledge frameworks. This process involves Knowledge Engagement, particularly in the transformation from “Theme” to “Concept” to “Framework.” A corresponding theoretical resource is the Concept Development framework.

The Frame-in-Use perspective addresses real-life activities that utilize knowledge frameworks as predictive models for Project Engagement. A corresponding theoretical resource is the Ecological Actualism framework.

The Frame-in-Diagram perspective emphasizes creating diagrams as representations of knowledge frameworks and predictive models. This perspective centers on Material Engagement. A corresponding theoretical resource is the Thematic Space Theory framework.

The Frame-in-Form perspective involves curating various knowledge frameworks into a meaningful whole, bridging THEORY and PRACTICE. This perspective focuses on Knowledge Curation and Theoretical Integration. A corresponding theoretical resource is the Ecological Formism framework.

Moreover, I introduced a fifth perspective, the Frame-in-Growth perspective, in a recent article: See the Move: Four Looks at the World of Activity Approach.

How can the “Milieu — Mediator — Method — Mastery” schema work with these perspectives?

I wrote a private note about the “Milieu — Mediator — Method — Mastery” schema on September 4, 2025.

On Sept 7, 2025, I revisited the “Ideation — Validation — Application — Reflection” schema and returned to the Knowledge Discovery canvas. Suddenly, I found that I could use the meta-canvas behind the Knowledge Discovery Canvas to curate these ideas together.

Theory, Practice, and Perspectives

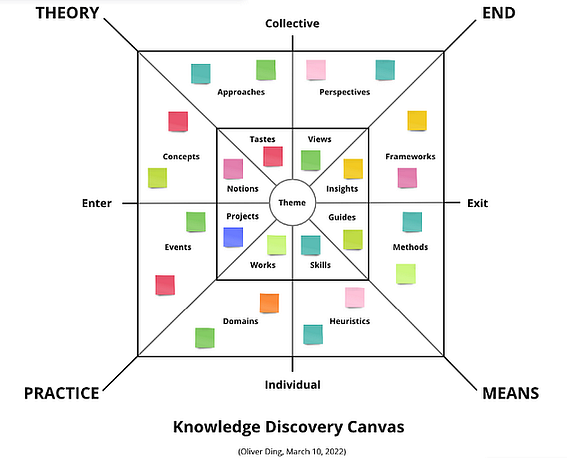

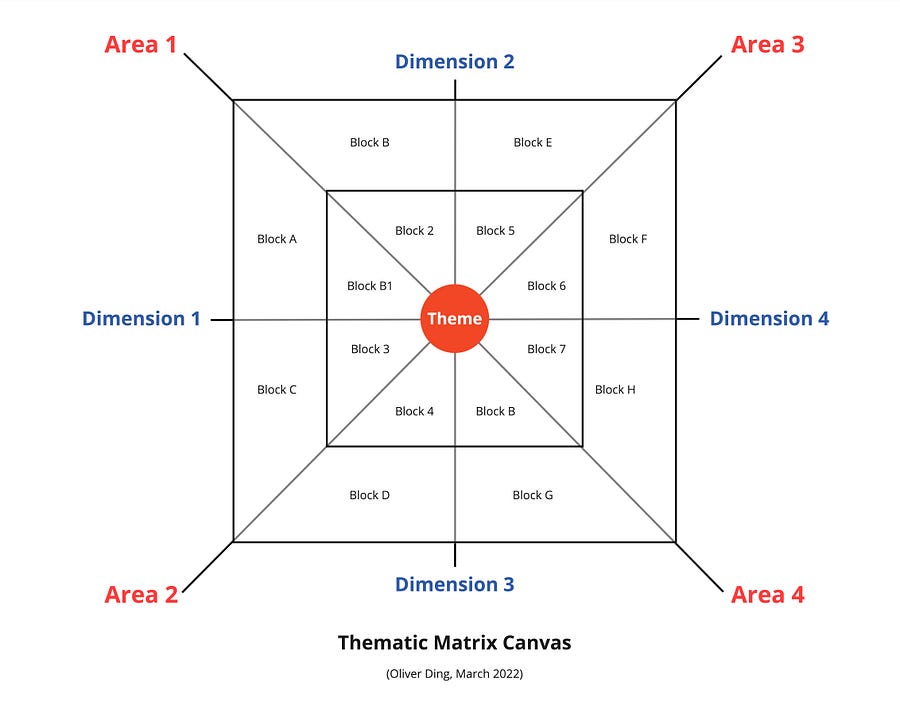

The Thematic Matrix Canvas (originally called Thematic Space Canvas) was developed as a meta-canvas to support the creation of canvases for developing theme-centered tacit knowledge.

A meta-canvas is an abstract canvas not tied to any specific domain. Its purpose is to highlight a unique spatial structure that can guide the design of domain-specific canvases.

In the meta-canvas, I use abstract terms such as area, dimension, block, and theme. See the diagram below.

The Thematic Matrix Canvas is not a simple 2x2 matrix for building a typology, but a multiple-dimension model designed to visualize a holistic view and make sense of a dynamic, meaningful whole. More details can be found here: The Notion of Thematic Spaces.

The spatial structure of the Thematic Matrix Canvas is organized around the following aspects:

- Four Significant Areas

- Four Dimensions

- Two Subspaces: Inner Space and Outer Space

- Eight Pairs of Blocks

- A Primary Theme

What makes the Thematic Matrix Canvas unique is its adoption of the Activity Theory perspective, treating the entire process of using the canvas as an activity. Moreover, it employs Inner Space and Outer Space to represent the internalization–externalization principle of Activity Theory.

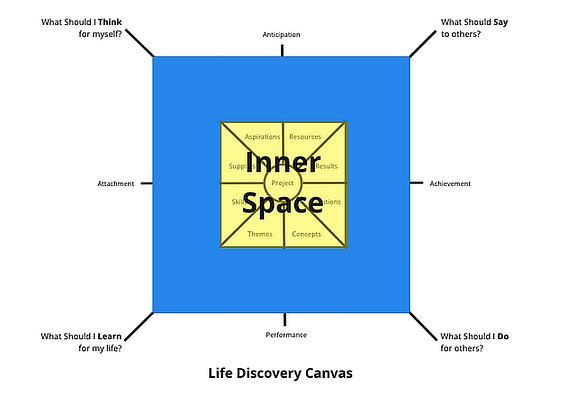

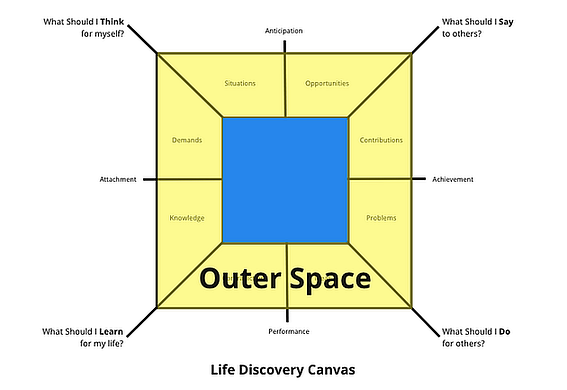

For example, the diagrams below are drawn from the Life Discovery Canvas.

The Thematic Matrix Canvas consists of 16 blocks, each providing space for adding notes. For example, the picture below illustrates a thematic space mapping called Center. When using a large-size canvas, you can place notes directly inside the blocks.

More details about the spatial structure can be found here.

For the Frame for Work canvas, the Inner Space is defined for “PRACTICE,” while the Outer Space is defined for “THEORY.”

The “PRACTICE — THEORY” Mapping is framed by eight perspectives.

- Frame in Form

- Frame in Make

- Frame in Spark

- Frame in Use

- Frame in Dialogue

- Frame in Case

- Frame in Diagram

- Frame in Text

These eight perspectives are based on four perspectives I used for the 2024 book draft, while also incorporating my more recent ideas.

The IDEATION Thematic Area

In the IDEATION thematic area, the Frame-in-Make perspective refers to developing a cultural concept as the core of a cultural framework. I refer to this type of practice as Concept Creation, while a corresponding theoretical resource is the Concept Dynamics Theory.

The Frame-in-Form perspective involves curating various cultural frameworks into a meaningful whole, serving as a bridge between THEORY and PRACTICE. This perspective focuses on Enterprise Curation and Theoretical Integration. A corresponding theoretical resource is the Ecological Formism framework.

The VALIDATION Thematic Area

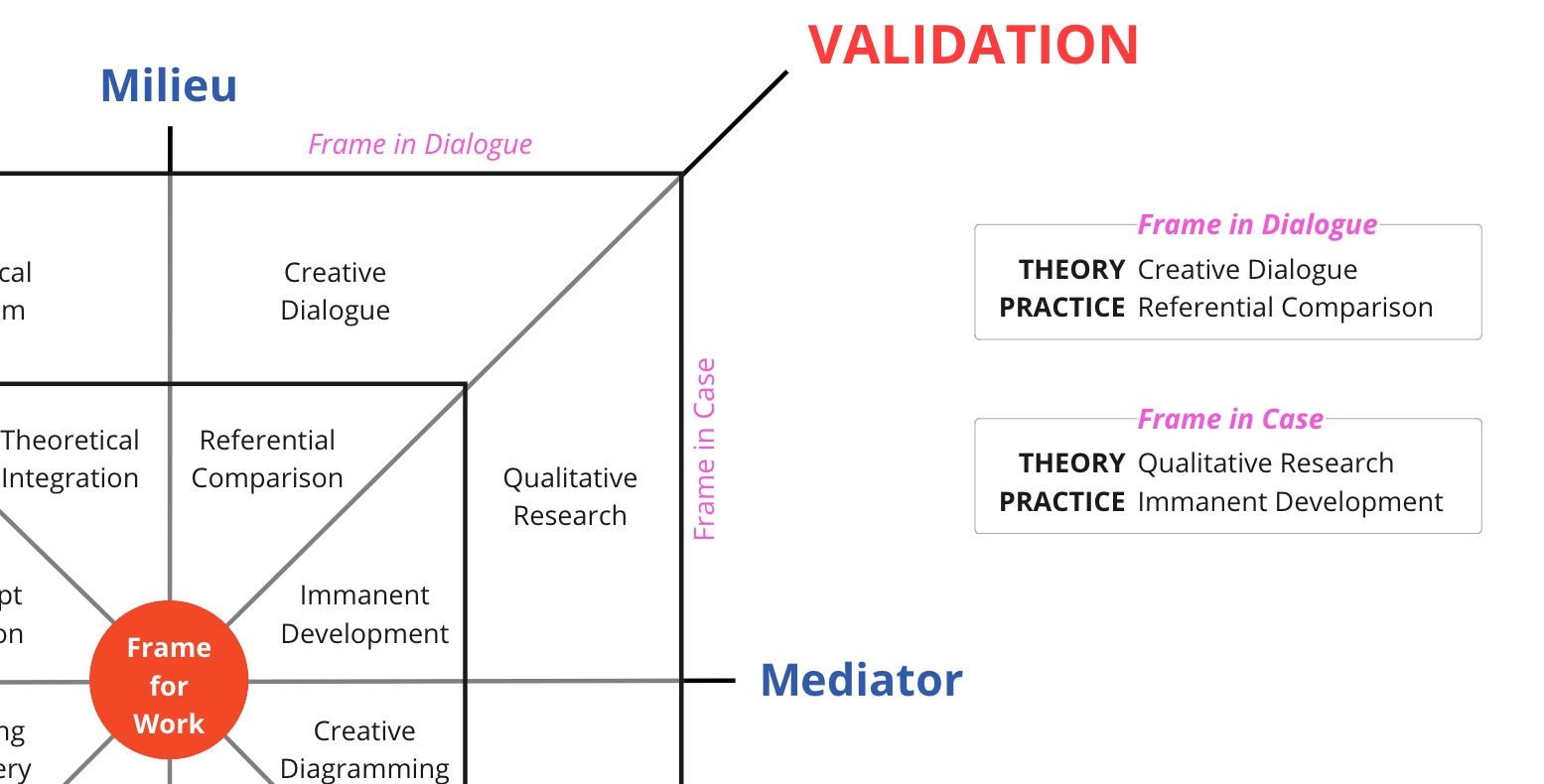

In the VALIDATION thematic area, I propose two ways of validation. The Referential Comparison practice refers to external validation. A cultural framework is established through comparison with other frameworks. A corresponding theoretical resource is the Creative Dialogue framework. This perspective is referred to as Frame-in-Dialogue.

The Immanent Development practice refers to the internal validation. By tracing the dynamic development of the process, a cultural framework could find its own essence. A corresponding theoretical resource is the Qualitative Research method, especially the historical-cognitive approach. This perspective is referred to as Frame-in-Case.

The APPLICATION Thematic Area

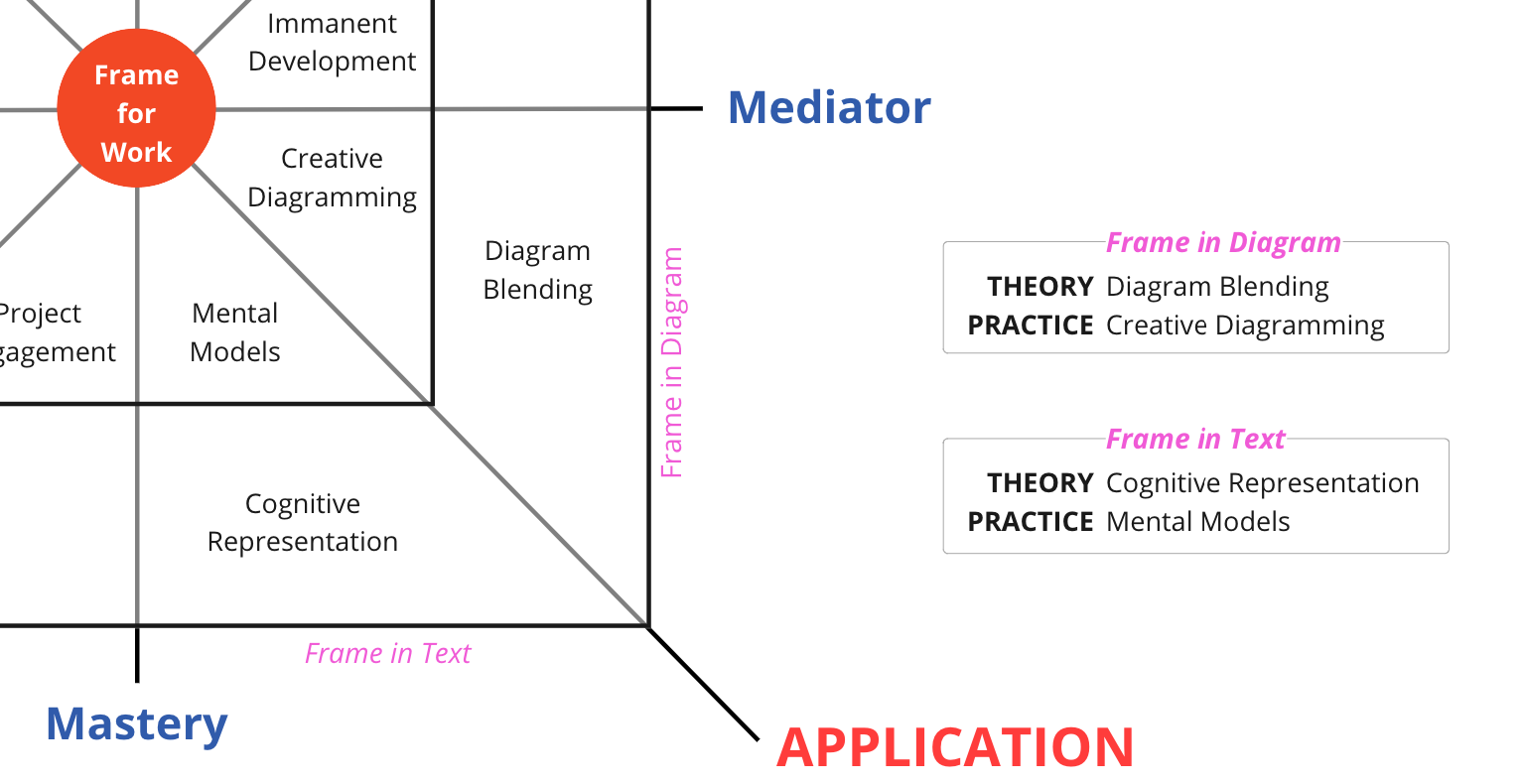

In the APPLICATION thematic area, the focus shifts to representing a cultural framework in real situations. The Frame-in-Diagram perspective highlights the value of diagrams and diagramming. I draw my book drafts on Creative Diagramming and Diagram Blending to explore this perspective.

The Frame-in-Text perspective refers to non-diagram representations. All cultural frameworks become mental models once learned by actors. The corresponding theoretical resource is the Cognitive Representation model.

The REFLECTION Thematic Area

In the REFLECTION thematic space, the individual actor's experience becomes the primary focus. The Frame-in-Use perspective highlights the Project Engagement practice, in which a cultural framework is embedded in actual projects. The corresponding theoretical resource is the Ecological Actualism framework.

The Frame-in-Spark perspective features the Meaning Discovery practice, and the Thematic Exploration framework is adopted as a theoretical resource.

More details about these practices and theoretical resources will be introduced in future articles.

Cultural Frameworks as Concept Systems

Both knowledge frameworks and cultural frameworks can be understood as concept systems. While the Knowledge Discovery Canvas focuses on developing tacit knowledge for knowledge engagement, the Frame-for-Work canvas focuses on building cultural frameworks for cultural innovation.

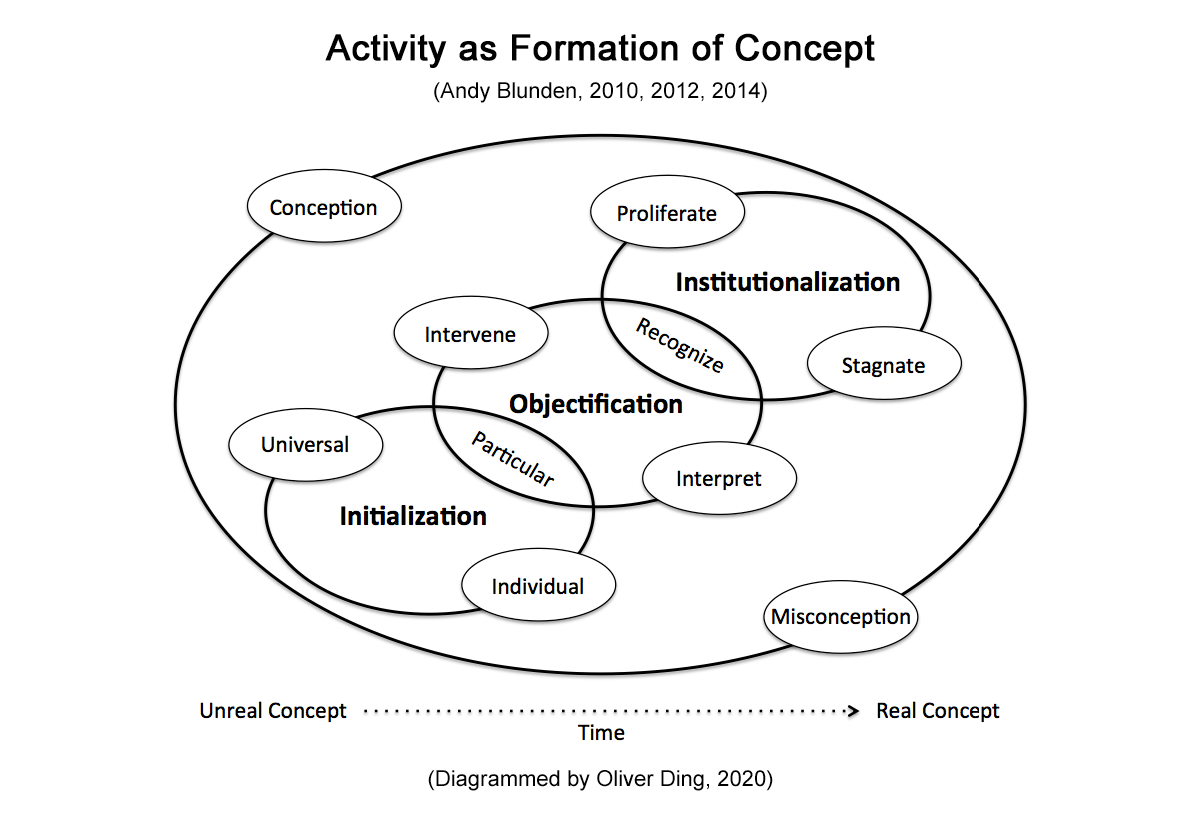

The Frame-for-Work canvas is part of my recent focus on cultural frameworks and cultural innovation. Since it treats a cultural framework as a concept system, it echoes my earlier work, my 2021 book draft, Project-oriented Activity Theory. In this draft, I introduced Andy Blunden's notion of "Activity as Formation of Concept."

According to Andy Blunden, there are three phases of the formation of concepts:

- Phase 1: Initialization;

- Phase 2: Objectification;

- Phase 3: Institutionalization.

The notion of three phases is inspired by Blunden’s case study “Collaborative Learning Space”. I have to point out that Blunden is relatively unconcerned with demarcating the boundaries between the successive phases of a project. We should consider the above diagram as a rough representation. Blunden definitely uses “Objectification” and “Institutionalization” in his writings. However, he doesn’t obviously use the term “Initialization”.

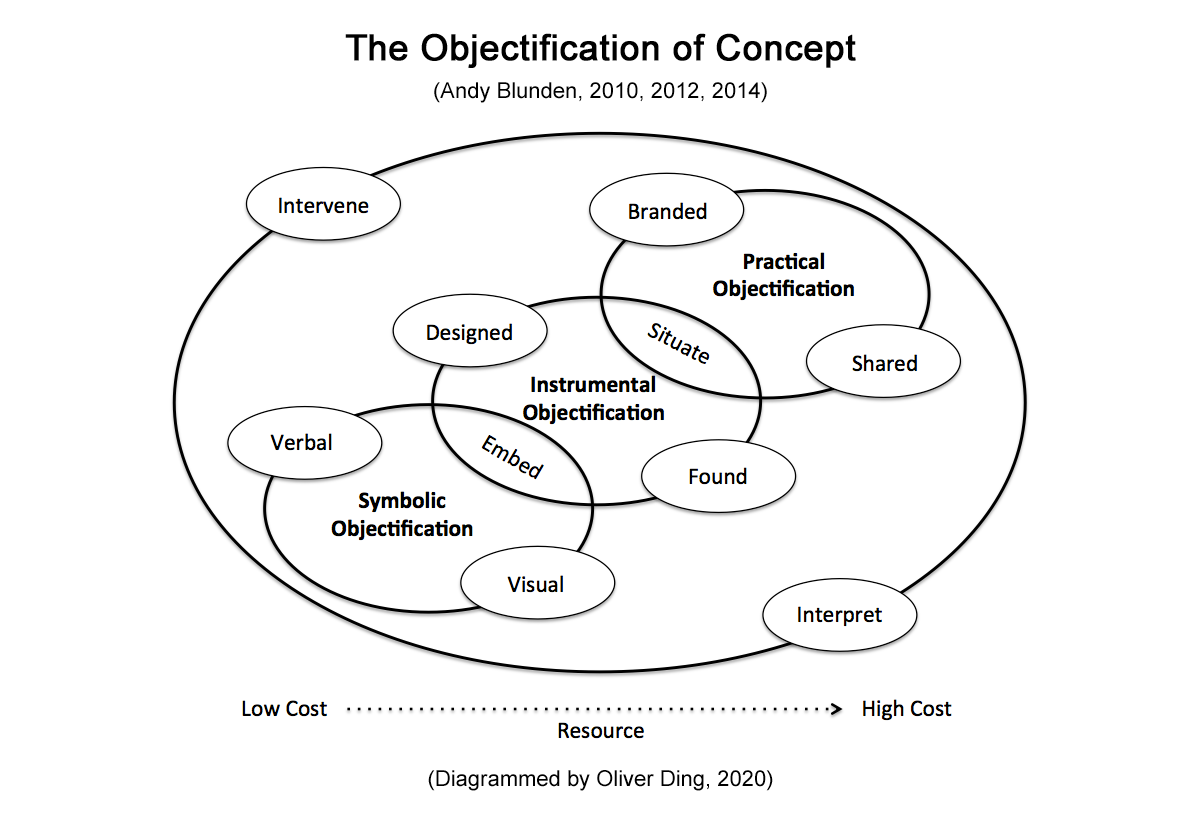

Blunden clearly claims that there are three aspects of objectification of concept: symbolic, instrumental, and practical. By adopting the germ-cell diagram, we can present these ideas with the diagram below.

More details can be found in Project-oriented Activity Theory and a case study about TEDx.

Blunden's approach is inspired by Hegel's theory of concepts, which is an abstract theoretical framework.

The Frame-for-Work Canvas is based on the “Ideation — Validation — Application — Reflection” schema. It expands Blunden's approach at the operational level, considering more significant aspects such as VALIDATION and REFLECTION.

Hegel's creative approach emphasizes triadic structures, with each level decomposed into three elements. In contrast, my Canvas framework highlights tetradic structures, as seen in the "Ideation-Validation-Application-Reflection" schema and the "Milieu-Mediator-Method-Mastery" schema. This structural difference reflects distinct cognitive orientations toward creative engagement.

According to Blunden, Hegel's approach also acknowledges that projects mature through four stages:

Taking a cue from Hegel, projects can be seen as passing through four stages in their development. (1) Firstly there will be some group of people who by virtue of their social position are subject to some taken-for-granted or impending problem or constraint on their freedom. These are the conditions for a project to exist, but the project has not yet come into being. (2) On becoming aware of the problem there will be a series of failed projects arising from misconceptions of the situation, until, at a certain point: (3) An adequate concept of the situation is formulated and named and a social movement is launched to change social practices so as to resolve the problem or injustice. As the project unfolds and interacts with the social environment, its object becomes clearer and more concrete. (4) Eventually, the new form of practice becomes 'mainstreamed' as part of the social practices of the wider community. That is, it is institutionalized and its concept enters into the language and culture of the community. These stages are to be seen as ideal-typical, not proscriptive. (Collaborative Projects: An Interdisciplinary Study, Andy Blunden, ed. 2014)

The "Ideation-Validation-Application-Reflection" schema roughly echoes these four stages. The first stage can be understood as IDEATION, the second stage as VALIDATION, and the third stage as APPLICATION. The fourth stage does not directly correspond to REFLECTION, as it does not emphasize the individual actor's experience, which is not the primary concern in Hegel’s abstraction.

However, the Frame-for-Work Canvas adopts the "Ideation-Validation-Application-Reflection" schema to define four types of thematic areas and a series of thematic spaces. The Canvas serves as a map for social action, while Hegel's four-stage approach outlines a particular path. Yet, there are other possible paths.

v1.0: September 26, 2025 - 3,657 words