Education as Anticipatory Activity

The "Anticipatory Cultural Sociology" Perspective

by Oliver Ding

January 14, 2025

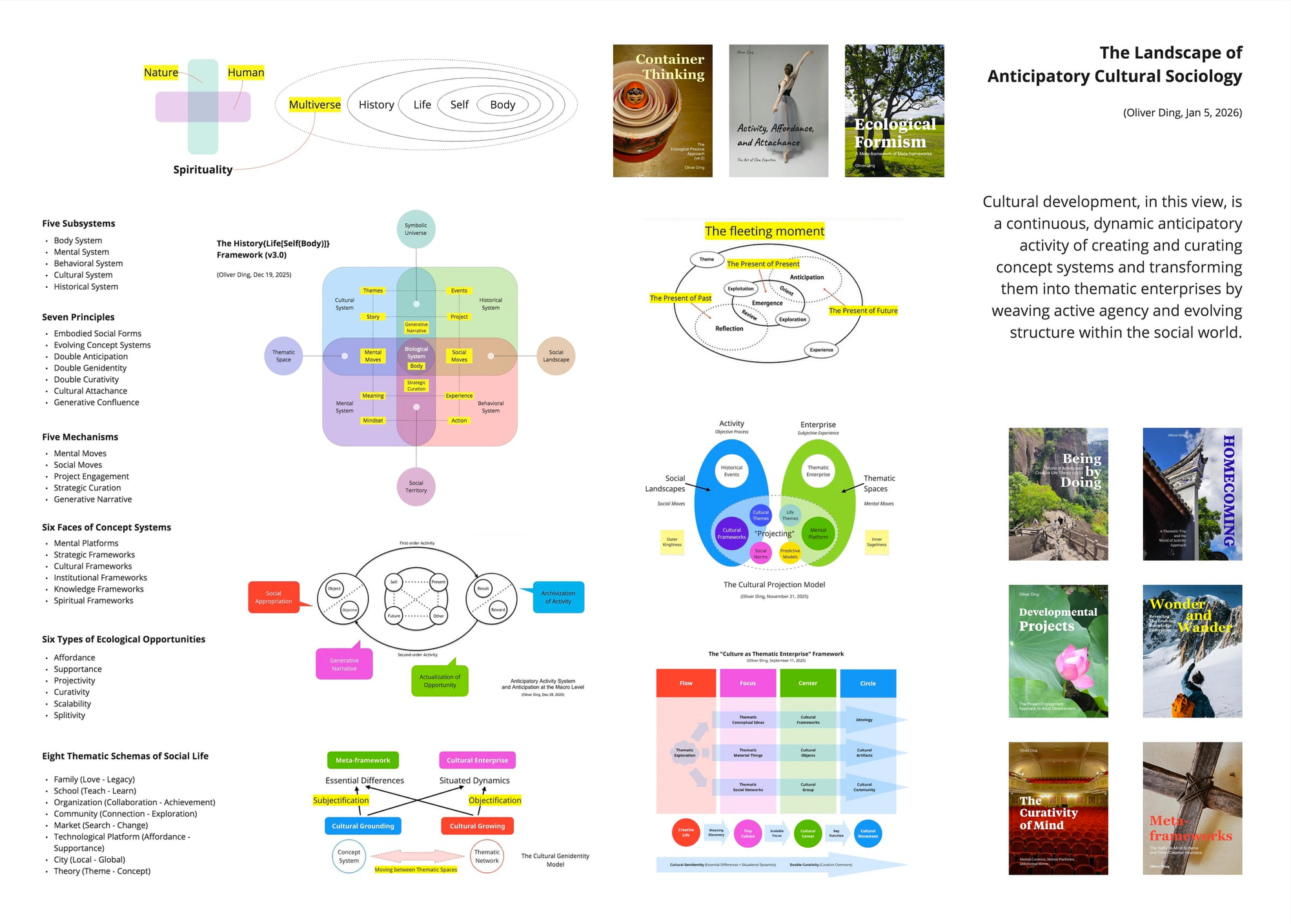

On December 31, 2025, I released a possible book, Meta-frameworks: Creative Heuristics for Individual and Social Development (book, v1.0, 2025), to close a several-year journey of knowledge engagement.

A major by-product of the project is the History{Life[Self(Body)]} Framework (v3.0), which understands the social world as a nested AAS (Anticipatory Activity System). The book proposes that,

Cultural development, in this view, is a continuous, dynamic anticipatory activity of creating and curating concept systems and transforming them into thematic enterprises by weaving active agency and evolving structure within the social world.

This statement goes beyond the book, but covers a series of book drafts I wrote and curated in the past year.

On January 5, 2026, I created a new diagram to curate the HLS Framework (v3.0) and other related frameworks, forming a new landscape of a thematic enterprise: Anticipatory Cultural Sociology (ACS). The term does not refer to a subfield of Cultural Sociology, but rather to a theoretical approach; therefore, it is more appropriate to call it the ACS approach.

The HLS framework was inspired by Robert Rosen’s Anticipatory System Theory, particularly his concepts of Natural Systems and Formal Systems. While Rosen's approach provides a systematic framework to understand life as an anticipatory system, it remains within the field of theoretical biology.

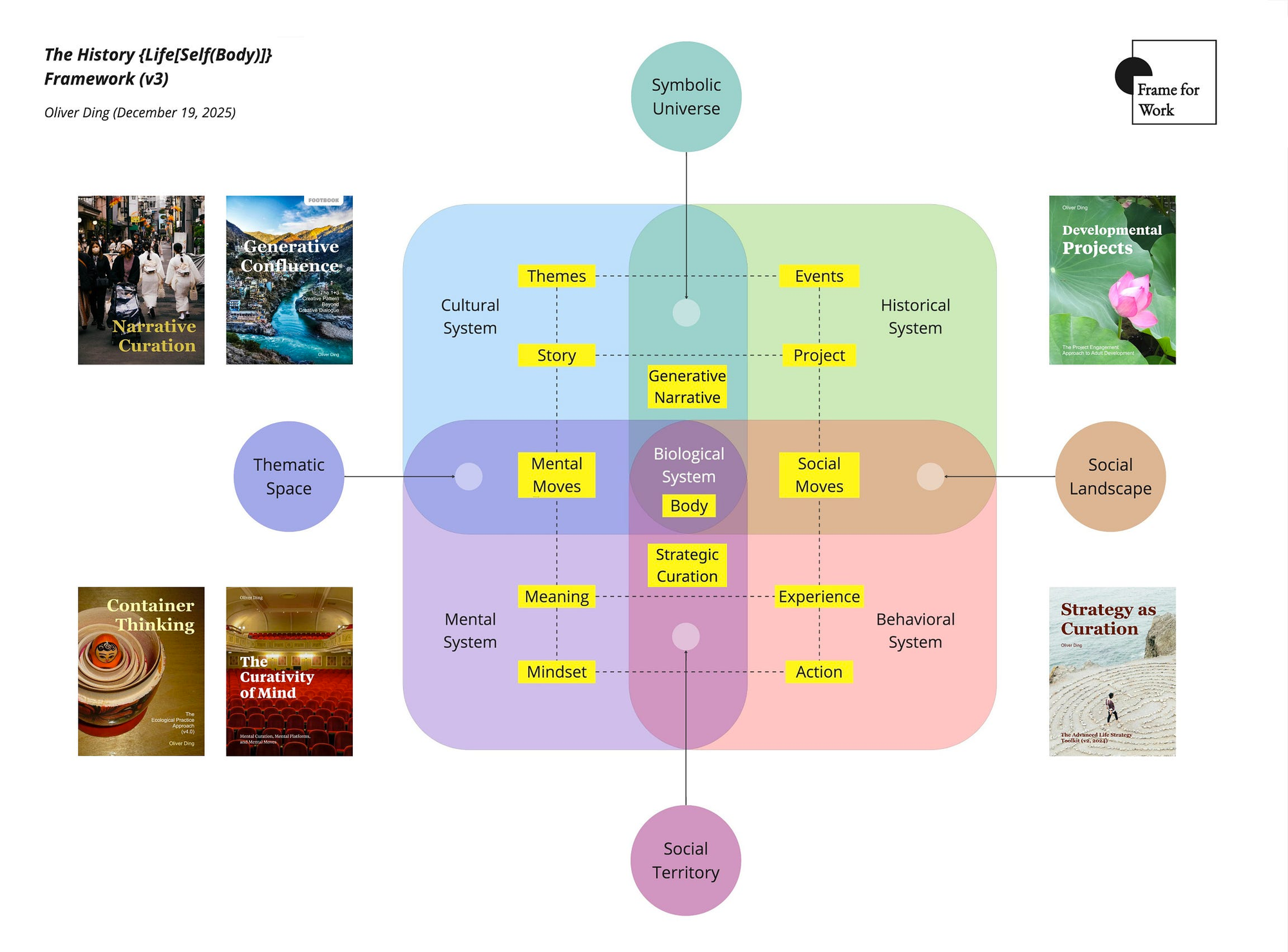

In 2021, drawing on Rosen’s distinctions and ideas from Activity Theory, I developed the Anticipatory Activity System (AAS) to understand adult life development. Later, in 2024, I developed the HLS framework, which conceptualizes the social world as a nested Anticipatory Activity System (AAS):

- Micro-AAS corresponds to the Mental System (Natural System).

- Macro-AAS corresponds to the Cultural System (Historical System).

For the Meta-frameworks project, the HLS framework provides a theoretical ontology of the social world, offering a structured context in which concept systems can be understood and mapped.

More details can be found in The Landscape of Anticipatory Cultural Sociology.

In the past several days, I have been in a conversation with a friend who is an education researcher at a university. Her recent focus is on the development of the Ed.D. program at the university and general reflection on educational practice.

Both Ed.D. (Doctor of Education) and Ph.D. (Doctor of Philosophy) provide the doctoral degree, yet they differ in purpose and program design. While the Ed.D. focuses on professional development, the Ph.D. guides students toward an academic pathway. In my friend's case, the Ed.D. program is designed as a part-time learning program for educational professionals.

Our conversation inspired a new theme, "Education as Anticipatory Activity," as a way to explore the ACS perspective in the field of education. This article aims to share early ideas related to this theme, opening a new thematic space for developing the "Education as Anticipatory Activity" (EAA) framework.

1. What's Anticipatory Activity?

As mentioned earlier, from the ACS perspective, cultural development is understood as a continuous, dynamic anticipatory activity. It involves creating and curating concept systems and transforming them into thematic enterprises by weaving active agency and evolving structure within the social world.

This view highlights several aspects of anticipatory activity:

- It is a historical process characterized by continuous dynamic development.

- Its primary objective lies in the transformation between concept systems and thematic enterprises.

- Its core actions include creating, curating, and weaving.

- It is situated in a social space where active agency and evolving structure intersect.

- It consists of real events that occur in the social world, rather than existing solely as imagination in the mind.

The ACS framework adopts the HLS framework to understand the social world through a five-system lens:

- Body System

- Mental System

- Behavioral System

- Cultural System

- Historical System

The framework was inspired by Robert Rosen’s Anticipatory System Theory, especially his ideas on Natural Systems and Formal Systems.

It sees the social world as a nested Anticipatory Activity System (AAS).

- The Micro AAS corresponds to the Mental System (Natural System).

- The Mega AAS corresponds to the Cultural System (Historical System).

The "Activity" component of Anticipatory Activity refers to the transformation between the Behavioral System and Historical System. It encompasses the following elements:

- Action

- Experience

- Social Moves

- Project

- Events

From the traditional perspective of Activity Theory, human activity is commonly understood as a hierarchical structure. Different activity theorists have proposed various concrete formulations of such hierarchies. My own solution, based on the Life as Activity approach, suggests the following levels:

- Operation

- Action

- Project

- Activity (e.g., Network of Projects, Anticipatory Activity System, Thematic Enterprise, etc)

- History

An action consists of a series of operations, and a project consists of a series of actions.

The Activity level refers to a higher-order level that encompasses a series of projects. At this level, several approaches have been developed to address the complexity of human activity from different perspectives:

- Network of Projects: highlights the networked aspect of human activity

- Anticipatory Activity System: highlights the anticipatory aspect of human activity

- Thematic Enterprise: highlights the subjective meaning aspect of human activity

The "Anticipatory" part of Anticipatory Activity refers to the transformation between the Mental System and the Cultural System, involving the following elements:

- Mindset

- Meaning

- Mental Moves

- Story

- Themes

While Mindset and Meaning are associated with the Mental System, Story and Themes are associated with the Cultural System. The transformation among these elements is grounded in the concept of the Predictive Model.

A core idea of Anticipatory System Theory is the Predictive Model. According to Robert Rosen, “An anticipatory system is a natural system that contains an internal predictive model of itself and of its environment, which allows it to change state at an instant in accord with the model’s predictions pertaining to a later instant.” In contrast, a reactive system only reacts, in the present, to changes that have already occurred in the causal chain, while an anticipatory system’s present behavior involves aspects of past, present, and future.

The HLS Framework is a nested Anticipatory Activity System (AAS) structure: the Behavioral System (Mental System) represents the micro-AAS, while the Historical System (Cultural System) represents the macro-AAS. The micro-AAS corresponds to individuals, and the macro-AAS to collective society.

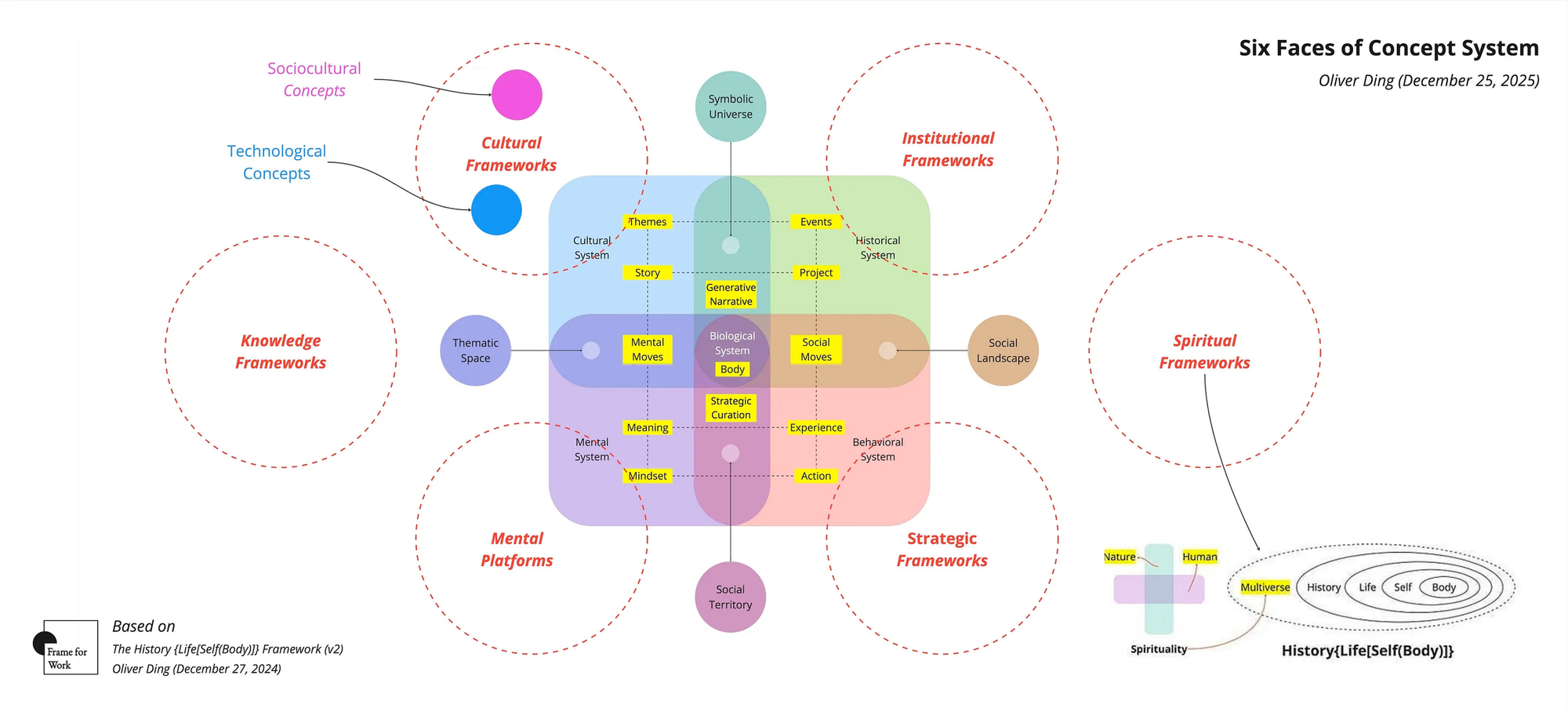

To apply the idea of "Predictive Model" to the social world, in the ACS framework, I defined Six Faces of Concept Systems:

- Knowledge Frameworks

- Mental Platforms

- Strategic Frameworks

- Cultural Frameworks

- Institutional Frameworks

- Spiritual Frameworks

In the middle of the diagram, four mappings are observed between four faces of the concept system and four core systems of the social world:

- Mental Platforms — Mental System

- Strategic Frameworks — Behavioral System

- Cultural Frameworks — Cultural System

- Institutional Frameworks — Historical System

Outside this central area, two types of concept systems — Knowledge Frameworks and Spiritual Frameworks — do not correspond directly to the core map of the social world. Their displacement toward the extreme poles of truth and meaning will be discussed in Part 3.

These mappings also reveal that two models share the same deep structure. The HLS Framework is a nested Anticipatory Activity System (AAS) structure: the Behavioral System (Mental System) represents the micro-AAS, while the Historical System (Cultural System) represents the macro-AAS. The micro-AAS corresponds to individuals, and the macro-AAS to collective society.

At the individual level, Mental Platforms belong to people, serving as the source of Strategic Frameworks, which target particular creative enterprises composed of a series of developmental projects.

At the collective level, Cultural Frameworks belong to social groups, while Institutional Frameworks emerge as evolving outcomes of Cultural Frameworks. In other words, past generations of Cultural Frameworks serve as the source of present Institutional Frameworks.

While Institutional Frameworks represent the crystallized history of human activity, Spiritual and Knowledge Frameworks represent the anticipatory horizon, pushing the Cultural System beyond its current limits.

Concept systems at individual and collective levels can influence each other. Individuals may adopt Cultural Frameworks to develop their Mental Platforms, while publicly shared Mental Platforms can contribute to new Cultural Frameworks. Similarly, some Institutional Frameworks can inspire Strategic Frameworks, and shared Strategic Frameworks can become part of Institutional Frameworks.

After defining the concept of Anticipatory Activity and exploring the ACS framework, we are ready to apply this perspective to the reflection on education, a significant form of human activity.

2. What is the Primary Form of Education?

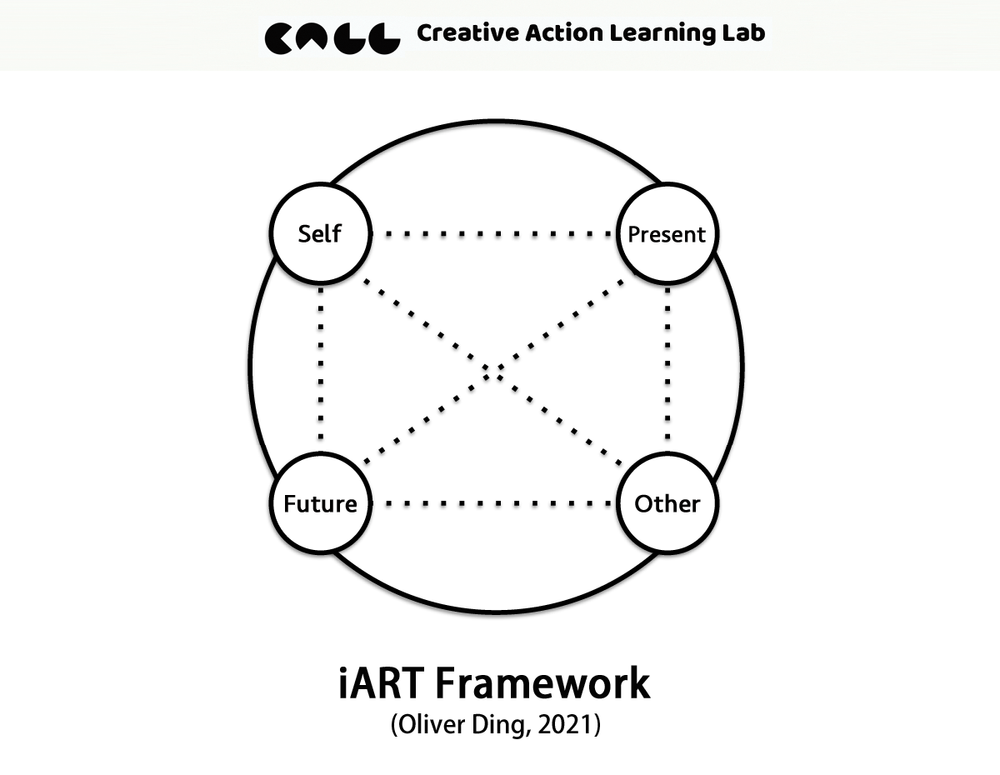

When viewed through the lens of ACS, education can be understood as a multi-layered Anticipatory Activity System that centers on a primary form of human life structured around four elements:

Self, Other, Present, Future

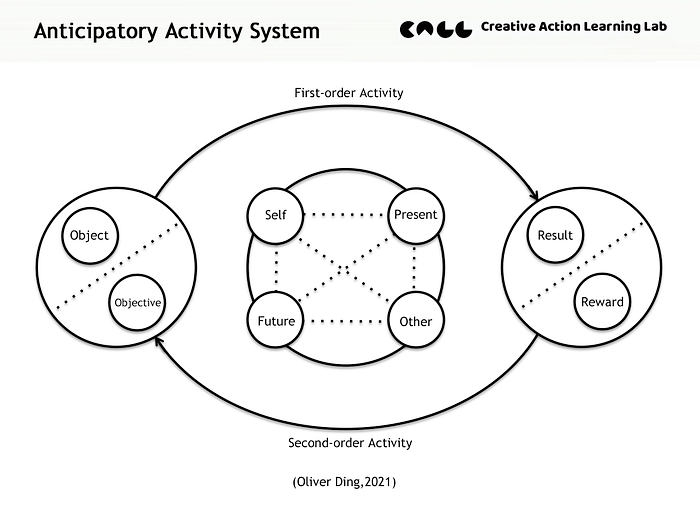

The Anticipatory Activity System (AAS) framework was originally developed in 2021 to understand the complexity of "Self, Other, Present, and Future" in human activity. Building upon the Activity Circle framework (Ding, 2017), which conceptualized human activity through four elements—Self, Other, Thing, and Think—the AAS framework introduces a temporal dimension:

- Self-Other: The relevance dimension, representing relationships between actors

- Present-Future: The anticipatory dimension, representing the temporal unfolding of activity

This structure is formed by two core components:

- First-order Activity: focused on achieving present objectives

- Second-order Activity: focused on discovering and shaping future possibilities

- The Self-Other Relevance: the relational context within which activities unfold

For understanding education as an anticipatory activity, we can see how:

- Present corresponds to the tangible objects, resources, and objectives available in the current moment

- Future corresponds to the anticipated goals, skills, capabilities, and career pathways

This reveals the inherently anticipatory nature of educational activity, where every "present" element is selected and shaped with a "future" in mind.

3. Four Nested Levels of Educational Activity

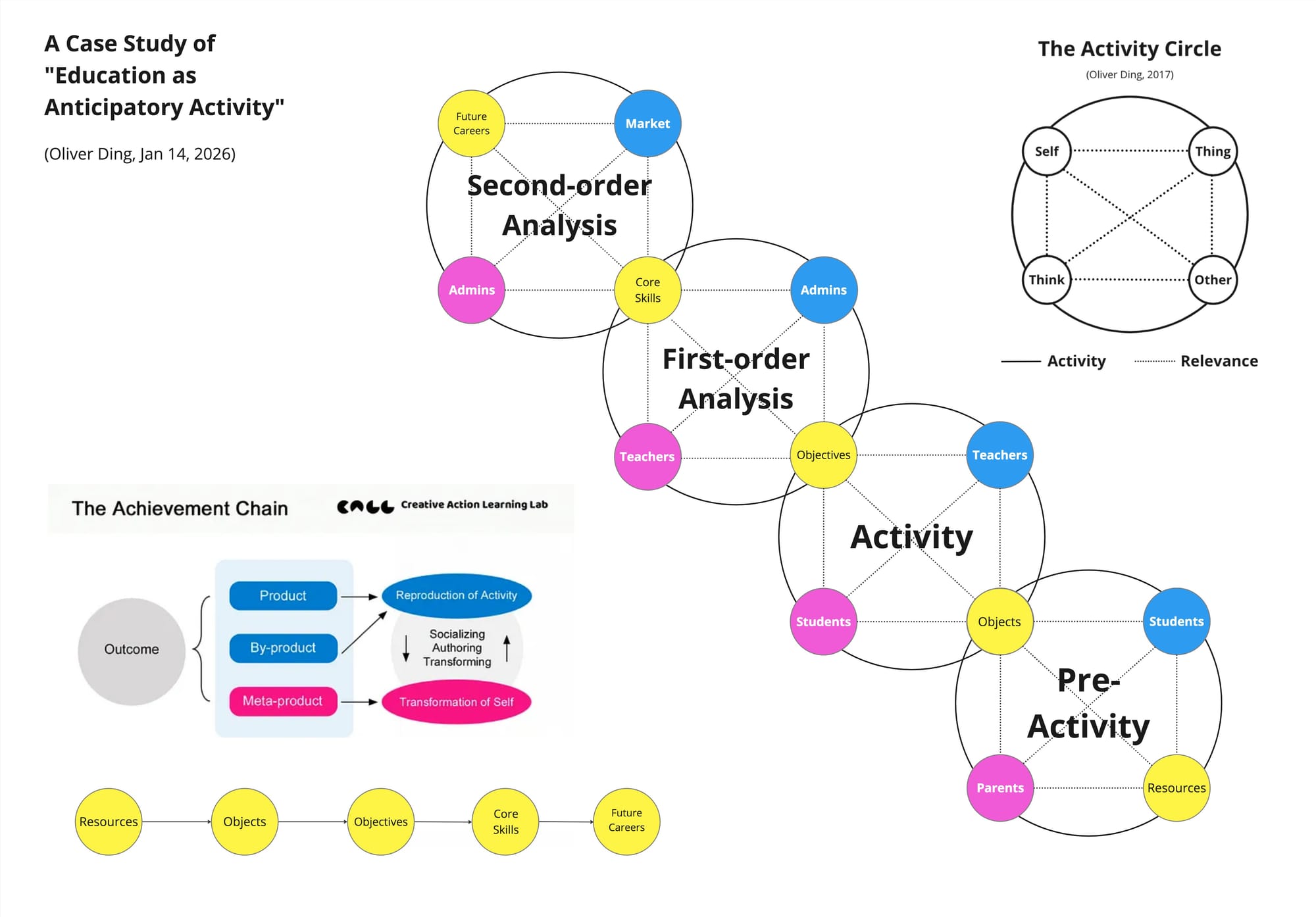

Based on four core elements of the AAS framework, I developed a new model to understand Education as Anticipatory Activity. See the diagram below.

The educational system operates as a nested anticipatory activity system across four distinct yet interconnected levels:

Level 0: Pre-activity (Parental Perspective)

- Self: Parents

- Other: Students (as potential learners)

- Present: Resources (books, toys, experiences, time, cultural capital)

- Future: Objects (learning materials students will encounter in school)

At this foundational level, parents curate and allocate resources, anticipating the learning objects their children will engage with in formal education. The family becomes the first site of anticipatory activity.

Level 1: Activity (Student Perspective)

- Self: Students

- Other: Teachers

- Present: Objects (learning materials, assignments, course content)

- Future: Objectives (course goals, learning outcomes)

Students engage with concrete learning objects in the present, guided by teachers toward specified educational objectives. This level represents the immediate educational experience.

Level 2: First-order Analysis (Teacher Perspective)

- Self: Teachers

- Other: Admins (administrators, educational policymakers)

- Present: Objectives (current teaching goals)

- Future: Core Skills (essential competencies students need for future careers)

Teachers translate institutional requirements into concrete learning objectives, anticipating the core skills students will need beyond the classroom. This level bridges immediate pedagogy with long-term capability development.

Level 3: Second-order Analysis (Administrative Perspective)

- Self: Admins

- Other: Market (labor market, industry trends, societal needs)

- Present: Core Skills (competencies aligned with future demands)

- Future: Future Careers (emerging professional pathways)

Educational administrators monitor market trends and societal changes, determining which core skills should be emphasized in curriculum design. This level connects educational institutions with broader social and economic dynamics.

4. The Achievement Chain

The four yellow elements in the diagram form what we call the Achievement Chain:

Resources → Objects → Objectives → Core Skills → Future Careers

This chain illustrates how educational value flows from family resources through institutional structures to eventual career outcomes. Each link in the chain represents a transformation:

- Resources become Objects through parental curation and institutional access

- Objects become Objectives through pedagogical design

- Objectives become Core Skills through sustained learning

- Core Skills become Future Careers through market alignment

Importantly, this is not a simple linear causation but a recursive anticipatory process where each level uses its predictive model of the next level to guide present actions.

The Achievement Chain produces three distinct types of outcomes:

Product: Reproduction of Activity

Direct learning outcomes that replicate existing knowledge and skills. Students master established content and can reproduce learned behaviors.

By-product: Transformation through Socializing, Authoring, and Transforming

Emergent outcomes from educational interactions. Students develop social capabilities, authorship of their learning, and capacity for adaptation.

Meta-product: Transformation of Self

The deepest level of educational outcome. Students develop the capacity to anticipate and shape their own futures—they internalize the anticipatory stance itself.

5. The Recursive Nature of Agency

A striking feature of this nested structure is how agency cascades through the levels:

- Parents are agents who anticipate for Students

- Students (as Other to Parents) become agents who engage with Objects

- Teachers (as Other to Students) become agents who design Objectives

- Admins (as Other to Teachers) become agents who define Core Skills

- Market (as Other to Admins) becomes the ultimate reference point

At each level, the "Other" of the current level becomes the "Self" of the next level. This cascade reveals how individual agency is always embedded within larger anticipatory systems.

What makes this structure genuinely anticipatory rather than merely sequential?

Each level operates with a predictive model of the next level:

- Parents hold predictive models of what Objects their children will encounter

- Students internalize predictive models of what Objectives teachers expect

- Teachers develop predictive models of what Core Skills the job market requires

- Admins maintain predictive models of Future Careers and societal needs

These predictive models are not passive predictions but active guides for present action. The "future" at each level structures the "present" at that level.

Moreover, the Future of one level becomes the Present of the next level:

- Parents' anticipated Objects become Students' actual learning materials

- Students' pursued Objectives become Teachers' working goals

- Teachers' targeted Core Skills become Admins' policy focus

- Admins' envisioned Future Careers become Market realities (or fail to)

This nested relationship creates a complex web of anticipations, where misalignments between levels generate tensions and opportunities for educational innovation.

6. A Concrete Example: Four Years of Undergraduate Education

To illustrate how this nested anticipatory structure operates in practice, let's examine the journey of an undergraduate student in the American university system through four years of education.

While this case reflects the specific institutional structure of U.S. higher education—including the liberal arts model, sophomore major declaration, and internship culture—the underlying anticipatory mechanisms it reveals can be found across different educational systems worldwide.

6.1 Year 1: Navigating the Transition

At the Pre-activity Level (Before University):

- Parents invest in Resources: SAT prep courses, college visits, application consulting

- They anticipate the Objects their child will encounter: college textbooks, lab equipment, online learning platforms, and lecture materials

At the Activity Level (Student's Experience):

- The freshman encounters Objects: introductory textbooks, problem sets, lab experiments, writing assignments, lecture notes, and online course materials

- These objects point toward Objectives: understanding basic concepts, developing study skills, achieving passing grades, and completing general education requirements

At the First-order Level (Faculty Perspective):

- Professors design courses with Objectives: critical thinking foundations, academic writing proficiency, and quantitative reasoning

- They anticipate Core Skills students need: analytical thinking, collaborative problem-solving, information literacy, time management

At the Second-order Level (Administrative Planning):

- University leadership monitors Core Skills demands: data literacy, cross-cultural competence, and ethical reasoning

- They anticipate Future Careers: emerging fields in AI, sustainability, healthcare, and digital media

The Misalignment Problem: Many freshmen struggle because the Objects they encounter (dense academic texts, abstract problem sets) don't clearly connect to the Objectives in their minds. Parents' Resources (test prep focused on standardized exams) may not adequately prepare students for the self-directed learning Objects of university life.

6.2 Year 2: Declaring a Major

The Pivotal Decision:

- Students must transform their engagement from general education Objects to discipline-specific Objects (major coursework)

- This decision represents a critical anticipatory moment: students choose based on their predictive models of future careers and personal interests

At the Activity Level:

- Objects become more specialized: research methods textbooks, coding assignments, case studies, fieldwork experiences

- Objectives sharpen: developing disciplinary knowledge, mastering technical skills, understanding theoretical frameworks

At the First-order Level:

- Department faculty design major curricula around Objectives that build toward Core Skills

- For a Computer Science major: programming proficiency → algorithmic thinking → system design → innovation capacity

- For a Sociology major: social theory comprehension → research methods → critical analysis → social insight

The Achievement Chain in Action: The sophomore's choice of major represents a crucial link in the Achievement Chain:

- Parents' early Resources (exposure to technology, encouragement of curiosity) influenced what Objects seemed accessible

- Freshman year Objects (intro CS course, sociology lecture) revealed possibilities

- Anticipated Core Skills (coding ability, social research) guide the major choice

- Imagined Future Careers (software engineer, policy analyst) justify the investment

6.3 Year 3: Building Specialized Competence

At the Activity Level:

- Objects intensify: advanced theory papers, independent research projects, internship applications, portfolio development

- Objectives evolve: demonstrating expertise, contributing original work, building professional networks

At the First-order Level:

- Faculty shift from teaching to mentoring, helping students see connections between Objectives and Core Skills

- Internship coordinators bridge academic Objectives and workplace Core Skills

At the Second-order Level:

- Career services track placement data, adjusting which Core Skills to emphasize

- Industry partnerships inform curriculum updates based on Future Career demands

The Internship as Boundary Experience: Summer internships represent a crucial test of the anticipatory system:

- Do the Objectives achieved in coursework translate to Core Skills valued by employers?

- Does the student's predictive model of their Future Career align with workplace reality?

- Positive experiences validate the Achievement Chain; negative experiences trigger recalibration

6.4 Year 4: Preparing for Transition

At the Activity Level:

- Objects culminate: senior thesis, capstone project, job applications, graduate school statements

- Objectives become tangible: degree completion, job offers, graduate admission, professional certification

The Meta-product Emerges: By senior year, successful students have internalized the anticipatory stance itself:

- They can identify Resources they need (online courses, networking events)

- They can transform Objects into learning opportunities (turning rejection into growth)

- They can articulate their Core Skills to potential employers

- They can refine their predictive models of Future Careers based on evidence

At the Second-order Level:

- Alumni outcomes data feeds back into curriculum design

- University rankings and employer feedback validate or challenge institutional anticipations

- Market shifts (rise of remote work, AI automation) force reconsideration of which Core Skills matter

6.5 The Three Outcomes Across Four Years

Products (Reproduction of Activity):

- Completed courses, earned credits, GPA

- Certificates, awards, technical proficiencies

- Portfolio pieces, published papers

By-products (Transformation through Practice):

- Leadership experience in student organizations

- Collaborative skills from group projects

- Professional identity development through internships

- Intellectual confidence from surviving difficult courses

Meta-products (Transformation of Self):

- Capacity to identify and pursue meaningful goals

- Ability to navigate ambiguity and complexity

- Resilience developed through academic challenges

- Most critically: the internalized ability to anticipate futures and work backward to determine present actions

6.6 Critical Tensions in the Four-Year Journey

Temporal Misalignment:

- Parents' Resources allocated based on 18-year-old predictions

- Freshman Objects designed based on outdated faculty experiences

- Core Skills emphasized based on 5-year labor market projections

- Future Careers imagined based on current trends that may disappear

Agency Gaps:

- Students often lack agency in Year 1-2 (following prescribed paths)

- Faculty have limited agency (constrained by departmental requirements)

- Administrators respond slowly to market changes (curriculum approval takes years)

The Privileged Anticipatory Advantage: Students from families with greater Resources (cultural capital, professional networks, financial security) can:

- Access better Objects (study abroad, unpaid internships, graduate exam prep)

- Receive more sophisticated guidance on connecting Objectives to Core Skills

- Take risks in pursuing Future Careers (entrepreneurship, creative fields)

This four-year journey illustrates why education must be understood as anticipatory activity: every decision, from course selection to major choice to career preparation, involves acting in the present based on models of the future. The quality of those predictive models—and the alignment between levels of the nested system—determines educational outcomes far more than any single factor like student effort or institutional resources.

7. Anticipatory Moments and Educational Systems

The undergraduate case study reveals a crucial insight: the number, timing, and distribution of anticipatory moments reflect the fundamental structure of an educational system. An anticipatory moment is a critical juncture where students (or their families) must make decisions based on predictive models of future possibilities. Different educational systems organize these moments in distinctly different ways.

7.1 The American Model: Distributed Anticipatory Moments

In the U.S. higher education system, anticipatory moments are spread across multiple years:

- High school course selection (AP, IB choices)

- College application (choosing institutions)

- First-year exploration (sampling different disciplines)

- Sophomore major declaration (the pivotal moment)

- Junior year internship selection

- Senior year career/graduate school decisions

This distribution creates a system of iterative anticipation: students make provisional decisions, gather feedback from experience, and adjust their predictive models. The sophomore major declaration represents the most significant anticipatory moment, but it occurs after students have already tested their interests and abilities through general education coursework.

7.2 The Chinese Model: Concentrated Anticipatory Moment

In China's Gaokao system, the primary anticipatory moment is highly concentrated:

- Gaokao examination and major selection (the decisive moment)

- Four years of deepening within the chosen major

- Limited opportunities for major transfer

- Graduate school entrance exam (a potential second major moment)

This creates a system of high-stakes anticipation: a single decision, made at age 17-18, largely determines the subsequent educational trajectory. The concentration of anticipatory pressure at this moment reflects a different philosophy of educational planning—one that prioritizes early commitment and deep specialization.

7.3 The British Model: Early Anticipatory Commitment

The UK system front-loads anticipatory moments:

- A-level subject selection (already beginning specialization)

- University application with a declared major

- Three years of focused study in a chosen field

- Fewer opportunities for exploration or redirection

This represents preemptive anticipation: students commit to a disciplinary path before entering university, based on earlier educational experiences and guidance.

7.4 Freedom and Constraint in Anticipatory Structures

The distribution of anticipatory moments directly correlates with what we might call anticipatory freedom—the degree to which students can revise their predictive models based on new experiences.

High Anticipatory Freedom (U.S. Model):

- Multiple decision points allow for course correction

- Students can test predictions against reality before committing

- Risk is distributed across several medium-stakes decisions

- Extends time in exploration but delays specialization

Low Anticipatory Freedom (Chinese Model):

- Single high-stakes decision concentrates risk

- Limited ability to revise predictions after initial commitment

- Early commitment enables deeper specialization

- Reduces exploration time but accelerates expertise development

Moderate Anticipatory Freedom (British Model):

- Early commitment with some built-in flexibility

- Balance between exploration and specialization

- Shorter degree duration reduces uncertainty period

7.5 Agency and Anticipatory Moments

Different systems also distribute anticipatory agency differently—who makes the predictive models that guide decisions?

In the American system:

- Students have substantial agency at the major declaration moment

- Parents influence through resource allocation but less direct control

- Institutional advisors provide guidance

- Market signals filtered through career services

In the Chinese system:

- Families often play a dominant role in the Gaokao decision

- Students' agency constrained by examination scores

- Social and economic pressures heavily influence choices

- Strong parental anticipation on behalf of students

In the British system:

- Students and families collaboratively anticipate during A-levels

- School guidance systems play significant role

- Earlier age of decision means more parental influence

- University admissions structure channels anticipation

7.6 Misalignment and System Stress

Each system's organization of anticipatory moments creates characteristic forms of stress and misalignment:

U.S. System Challenges:

- Extended exploration period can feel directionless

- Multiple decision points create ongoing anxiety

- "Major switching" reveals failed predictions but enables correction

- Gap between general education and career preparation

Chinese System Challenges:

- Immense pressure on a single anticipatory moment

- When predictions fail, limited recourse for adjustment

- Major-job misalignment creates post-graduation difficulties

- Students may lack a genuine understanding of chosen fields

British System Challenges:

- Early commitment based on limited self-knowledge

- Premature specialization may foreclose options

- Difficulty redirecting if initial predictions prove wrong

- Less space for interdisciplinary discovery

7.7 The Meta-Product Across Systems

Despite these structural differences, all systems aim to produce the same meta-product: students who can engage in anticipatory activity independently. However, different systems cultivate this capacity through different mechanisms:

U.S. model develops anticipatory capacity through iterative practice: students learn by making multiple predictions, experiencing outcomes, and refining models.

Chinese model develops anticipatory capacity through concentrated preparation: students learn by investing deeply in a single major prediction, developing commitment and perseverance.

British model develops anticipatory capacity through early responsibility: students learn by making consequential decisions at younger ages with appropriate support.

7.8 Implications for Cross-Cultural Understanding

This analysis reveals that debates about "which educational system is better" often miss the point. Each system embodies different assumptions about:

- When students are ready to make consequential anticipatory decisions

- How much exploration is necessary before commitment

- Who should hold primary anticipatory agency (students, families, institutions)

- What kind of anticipatory capacity should education develop

Understanding education as anticipatory activity helps us see these differences not as deficiencies but as alternative ways of organizing the relationship between present and future, self and other, individual and society.

7.9 The Evolution of Anticipatory Structures

Interestingly, all three systems show signs of evolution:

- U.S. system is adding more structure to exploration (learning communities, meta-majors, career pathways)

- Chinese system is experimenting with more flexibility (minor programs, interdisciplinary options, transfer policies)

- British system is incorporating more breadth (foundation years, joint honors degrees)

These changes suggest a gradual convergence toward systems that balance anticipatory freedom (allowing revision of predictions) with anticipatory guidance (providing structure for decision-making). The question is not whether to have anticipatory moments, but how to distribute them in ways that develop students' capacity for lifelong anticipatory activity.

This cross-system comparison demonstrates the analytical power of viewing education as anticipatory activity. It allows us to see beyond surface differences in curriculum or credentials to the deeper structures that shape how students learn to anticipate and prepare for their futures.

8. From Activity Analysis to Concept Systems

The case study of Education as Anticipatory Activity reveals several key insights about how anticipatory structures operate in practice:

Education is inherently anticipatory. Every educational action, from parental resource allocation to curriculum design, embodies anticipations about future states. The Achievement Chain (Resources → Objects → Objectives → Core Skills → Future Careers) illustrates how present investments are always made in service of imagined futures.

Agency is distributed and nested. No single actor controls the educational process. Parents, students, teachers, and administrators each exercise agency within constraints set by other levels. The recursive structure shows how the "Other" at one level becomes the "Self" at the next, creating a cascade of anticipatory activity.

Anticipatory moments structure educational systems. The number, timing, and distribution of critical decision points fundamentally shape educational experiences. Different systems organize these moments differently, reflecting different assumptions about readiness, exploration, and agency.

The Achievement Chain is fragile. Each transformation depends on alignment between levels. Resources don't automatically become Objects; Objectives don't automatically develop Core Skills. Educational quality requires careful attention to these transformations and the predictive models that guide them.

Meta-products are crucial. The ultimate success of education lies not in reproducing existing knowledge (Products) or even in developing specific competencies (By-products), but in cultivating students' capacity for anticipatory activity itself (Meta-products).

These insights raise critical questions: How do misalignments between levels create educational problems? How can we improve the quality of predictive models at each level? How do students develop their own anticipatory capacities through participation in this nested system?

8.1 The Role of Concept Systems

These questions bring us back to the core framework of Anticipatory Cultural Sociology. The predictive models that operate at each level of the educational system are not abstract mental constructs—they take concrete form as concept systems. As introduced at the beginning of this article, the ACS framework identifies six faces of concept systems, each mapped onto specific systems within the HLS framework:

At the core of the social world, four faces correspond to four systems:

Mental Platforms ↔ Mental System: These are the internalized conceptual structures that individuals use to make sense of their educational experiences. Students develop mental platforms that help them navigate choices, interpret feedback, and anticipate possibilities. A student's mental platform might include beliefs about their learning abilities, frameworks for understanding different subjects, and models of what success means.

Strategic Frameworks ↔ Behavioral System: These guide action at the individual and institutional levels, translating abstract goals into concrete plans. A student's study strategy, a teacher's lesson plan, and a department's curriculum design all function as strategic frameworks that organize behavior toward anticipated outcomes.

Cultural Frameworks ↔ Cultural System: These embody shared assumptions about education's purpose and value. They shape what counts as success, which skills matter, and what futures are worth pursuing. Cultural frameworks operate powerfully at the Administrative and Market levels of our educational model.

Institutional Frameworks ↔ Historical System: These are the crystallized structures that emerge from past Cultural Frameworks—degree requirements, accreditation standards, hiring practices, grading systems. They represent the "memory" of the educational system, both constraining and enabling present action. Institutional frameworks are what past generations of educators and policymakers have left behind as the structured reality of education.

Beyond the operational core, two faces mark the boundaries:

Knowledge Frameworks are displaced toward the lower boundary, representing the pursuit of objective truth independent of immediate social interests. In education, these include learning sciences, developmental psychology, and pedagogical research—systematic knowledge about how learning works.

Spiritual Frameworks are displaced toward the upper boundary, addressing ultimate meaning and transcendent purposes. They ask: What kind of human beings should education cultivate? What kind of society do we hope to create? These frameworks point beyond immediate practical concerns to existential significance.

8.2 Temporal Dynamics: From Cultural to Institutional

A crucial insight from the HLS framework is the temporal relationship between concept systems:

At the individual level, Mental Platforms serve as the source of Strategic Frameworks. A student's internalized understanding of learning (mental platform) generates specific study strategies and project choices (strategic frameworks). These strategic frameworks target particular creative enterprises—a senior thesis, a career preparation plan, a research project.

At the collective level, past generations of Cultural Frameworks serve as the source of present Institutional Frameworks. The liberal arts ideal that dominated American higher education in the mid-20th century (a cultural framework) has crystallized into current general education requirements (institutional frameworks). What was once a contested vision has become an established structure.

While Institutional Frameworks represent the crystallized history of human activity, Knowledge Frameworks and Spiritual Frameworks represent the anticipatory horizon—pushing the cultural system beyond its current limits, challenging existing practices, and imagining alternatives.

8.3 The Case of "Core Skills": Concept Systems in Action

The concept of "core skills" exemplifies how concept systems function as cultural frameworks in practice—and how they transform across different faces of the concept system.

Consider how different organizations continuously define and redefine what constitutes essential competencies:

- The OECD promotes "21st Century Skills" emphasizing critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, and communication

- The World Economic Forum publishes evolving lists of skills for the "Future of Work," recently highlighting complex problem-solving, analytical thinking, and technological literacy

- Tech companies advocate for STEM competencies, coding literacy, and digital fluency

- Liberal arts institutions defend the enduring value of written communication, historical thinking, and ethical reasoning

- Employer associations emphasize "soft skills" like adaptability, emotional intelligence, and cross-cultural competence

Each "core skills" framework is not merely a descriptive list—it is a predictive model embedded in a cultural framework. When the World Economic Forum declares certain skills as essential, it makes an anticipatory claim about future labor markets. When universities defend liberal arts competencies, they assert a competing vision of what futures matter.

These cultural frameworks then transform across the faces of concept systems:

- Cultural Framework → Institutional Framework: Universities adopt these frameworks into degree requirements and accreditation standards. The OECD's "21st Century Skills" become institutionalized as learning outcomes in curriculum documents. What was a vision becomes policy.

- Cultural Framework → Strategic Framework: A computer science department develops a new curriculum that balances industry-demanded technical skills with the university's commitment to ethical reasoning. The cultural framework is translated into specific course sequences and pedagogical strategies.

- Cultural Framework → Mental Platform: Students internalize competing frameworks as they make educational choices: "Should I focus on coding skills that employers want now, or broader analytical capacities that might matter in unknown future contexts?" The cultural debate becomes a personal cognitive struggle.

- Strategic Framework → Institutional Framework: When many departments adopt similar strategic reforms, these eventually crystallize into institutional standards. Shared strategic frameworks can become part of institutional frameworks.

- Mental Platform → Cultural Framework: When influential educators publicly share their mental platforms—their personal theories of what education should be—these can contribute to emerging cultural frameworks. A professor's innovative teaching philosophy, widely adopted, becomes part of the cultural conversation.

- Institutional Framework → Strategic Framework: Existing degree requirements constrain but also inspire new strategic approaches. A teacher designs a course that fulfills general education requirements while pursuing innovative pedagogical goals.

This dynamic interplay reveals several crucial insights:

Concept systems are never isolated. They constantly transform into each other. A cultural framework today may become an institutional framework tomorrow. An individual's mental platform, when shared and adopted, can influence cultural frameworks.

Educational innovation requires working across multiple faces. Introducing new ideas solely as cultural frameworks (visions and values) without attention to strategic frameworks (concrete implementation) or institutional frameworks (structural support) leads to failure. Effective change agents understand which concept systems need to shift and in what sequence.

Conflict between concept systems is inevitable and generative. When a student's mental platform conflicts with institutional frameworks, or when emerging cultural frameworks clash with established institutional ones, these tensions drive both personal development and systemic reform.

The struggle over "core skills" is fundamentally a struggle over predictive models. No one actually knows what skills will matter in 2040. Different organizations offer competing predictive models, each backed by different forms of authority—research data, employer surveys, philosophical argument, market power. By establishing which concept systems should guide educational practice, these organizations shape whose visions of the future will become self-fulfilling prophecies.

This is why education as an anticipatory activity is never merely technical—it is always also political and cultural. The competition between different "core skills" frameworks is a competition over whose anticipations will be institutionalized, whose predictions will guide present action, whose futures will be realized.

8.3 The Central Proposition Revisited

This analysis returns us to the central proposition of Anticipatory Cultural Sociology:

Cultural development is a continuous, dynamic anticipatory activity of creating and curating concept systems and transforming them into thematic enterprises by weaving active agency and evolving structure within the social world.

Education, viewed through the lens of anticipatory activity, exemplifies this process precisely:

- Creating concept systems: Organizations continuously develop new frameworks for understanding core skills, learning outcomes, and pedagogical approaches.

- Curating concept systems: Educators select from competing frameworks, integrating them into coherent approaches that fit local contexts.

- Transforming into thematic enterprises: These concept systems don't remain abstract—they become actual educational programs, degree pathways, teaching practices, assessment systems.

- Weaving active agency and evolving structure: Individual actors (students, teachers, administrators) exercise agency in adopting, resisting, or modifying these frameworks, while the frameworks themselves shape what actions are possible. The structure evolves through this ongoing interaction.

The power of viewing education through the ACS lens is that it reveals these concept systems not as static repositories of information, but as living predictive models that guide anticipatory activity across nested levels. When we ask "How can we improve the quality of predictive models?" we are asking: How can we develop better concept systems—more accurate knowledge frameworks, more flexible mental platforms, more responsive strategic frameworks, more inclusive cultural frameworks, more adaptive institutional frameworks, more inspiring spiritual frameworks?

The case study demonstrates that concept systems are not merely intellectual constructions; they are the actual mechanisms through which anticipatory activity operates. They are the means by which present action connects to imagined futures, the tools by which individuals and institutions navigate uncertainty, and the structures through which agency is exercised and constrained across nested levels of the social world.

Conclusion

Education, viewed as anticipatory activity, is a vast, multi-level enterprise of creating, curating, and transforming concept systems to shape individual lives and collective futures. The Self-Other-Present-Future structure recursively manifests across four nested levels—from parental resource allocation to market-driven career pathways—revealing education not as knowledge transmission or skill development, but as anticipatory transformation.

The nested anticipatory structure shows that educational improvement cannot focus on a single level in isolation. We must attend to the anticipatory relationships between levels and work to align the predictive models that guide action at each level. A parent's investment in resources only yields value if those resources connect to meaningful objects in school; a teacher's carefully designed objectives only develop core skills if institutional structures support the transformation; administrators' curriculum reforms only succeed if they align with actual labor market demands—and, crucially, if students can internalize these frameworks as meaningful mental platforms.

Most fundamentally, the analysis reveals that education's ultimate purpose is not to fill students with knowledge for an imagined future, but to develop their capacity to engage in anticipatory activity themselves—to identify resources, transform objects into learning opportunities, refine predictive models based on evidence, navigate competing concept systems, and shape their own futures with agency and purpose.

The Education as Anticipatory Activity framework is itself a concept system—a new lens for seeing, analyzing, and potentially reforming one of humanity's most fundamental anticipatory projects. By making visible the nested structure of anticipatory relationships, the distribution of anticipatory moments, the transformation dynamics between different faces of concept systems, and the role of competing cultural frameworks, it offers tools for understanding persistent educational problems and imagining new possibilities.

As we continue to develop the Anticipatory Cultural Sociology approach, education serves as a rich domain for exploring how human beings collectively navigate uncertain futures through the creation, curation, and transformation of concept systems. The insights gained here illuminate patterns that extend far beyond education—to organizational strategy, technological innovation, social movements, and all domains where human agency and evolving structures meet in the ongoing work of cultural development.

v1.0 - January 14, 2026 - 6,410 words

A Note on Collaborative Writing

This article was written through a collaborative process between the author (Oliver Ding) and Claude (Anthropic's AI assistant). The collaboration unfolded as follows:

- Initial Development: On the morning of January 14, 2026, the author drafted the introductory sections of "Education as Anticipatory Activity," establishing the ACS (Anticipatory Cultural Sociology) perspective and outlining the article's structure. After lunch, the author decided to shift from the comprehensive outline to a focused case study centered on a specific analytical model. Based on the Activity Circle model, the author designed a diagram to represent this model.

- Model Explanation: Through a conversational exchange, the author explained the new diagram, which is based on the core structure of the Self-Other-Present-Future model and its recursive manifestation across four nested levels of educational activity (Pre-activity, Activity, First-order Analysis, Second-order Analysis). The author provided detailed mappings of each level and clarified how the model derives from the Activity Circle framework developed in 2017.

- Collaborative Writing: The AI assistant drafted the case study sections based on the author's theoretical framework and specific instructions. The author then reviewed these drafts, providing feedback and requesting revisions. For example, when the AI initially created a case study focused on American undergraduate education, the author requested that the cultural specificity be explicitly acknowledged while maintaining the analytical framework's broader applicability.

- Theoretical Extensions: The author introduced additional theoretical dimensions during the conversation, such as the extension to "Pre-activity" (parental level) and the concept of "anticipatory moments" as structural features of educational systems. The AI assistant then developed these ideas into full sections, including the cross-system comparison (Section 7) and the connection to concept systems (Section 8).

- Iterative Refinement: Multiple rounds of revision occurred, particularly for Section 8 ("From Activity Analysis to Concept Systems"). After the author provided two key articles from the Meta-frameworks project—"Six Faces of the Concept System" and "Weave the Culture"—the AI assistant completely rewrote this section to accurately reflect the author's theoretical framework, including the proper mapping relationships, temporal dynamics, and the "Core Skills" example.

- Structural Organization: The author guided the overall structure, requesting that future research directions be condensed and that the conclusion be refocused to connect back to the ACS framework's core proposition about concept systems as mechanisms of cultural development.

- Author's Role: The author provided all theoretical frameworks, conceptual innovations, diagrams, and analytical insights. The author's intellectual property includes the ACS framework, the HLS framework, the Six Faces of Concept Systems, the Activity Circle, all related concepts, and diagrams.

- AI's Role: The AI assistant served as a writing collaborator, helping to articulate the author's ideas, organizing complex theoretical material into readable sections, and generating examples that illustrated theoretical points. The AI also offered structural suggestions and helped identify areas where additional clarification might enhance reader understanding.

This collaborative approach allowed the author to focus on theoretical development and conceptual precision while leveraging the AI's capacity for rapid drafting and iterative revision. The final article represents the author's theoretical vision, articulated through human-AI collaboration.