Mindentity: The Ontology of Thematic Creation

From Psychological Ownership to Ecological Objectification

by Oliver Ding

January 23, 2026

Today, I revisited the concept of “Mindentity” I created in August 2017. At that time, I was working on developing a series of knowledge frameworks around emerging digital formations such as blockchain projects and virtual communities. These formations presented a paradox: they often lacked clear legal status or physical boundaries, yet possessed a distinct and undeniable reality in the minds of their participants — revealing a theoretical gap in how social reality is conventionally defined.

To address this gap, I coined a new term, Mindentity, by combining Mind and Entity. To establish its ontological status, a distinction was drawn between the Legal Level and the Psychological Level (see the diagram below).

- Entity: Defined by legal ownership and clear physical or corporate boundaries.

- Mindentity: Defined by psychological reality and consensus.

The concept of Mindentity led to the formulation of a first principle of social creation:

All entities are mindentities, but not all mindentities are entities.

This principle suggests that Mindentity functions as a broader ontological container than the traditional legal entity, capturing forms of social reality that exist prior to formal ownership, institutionalization, or juridical recognition.

Although this idea emerged early, I did not continue developing it after late 2018. Instead, my focus shifted toward writing my first theory book, Curativity, initiating a six-year trajectory of theoretical exploration across creative life, activity, and knowledge engagement.

The recent formation of a new thematic enterprise — Anticipatory Cultural Sociology — prompted me to revisit these earlier ideas. In doing so, I realized that Mindentity provides a missing ontological layer that fits naturally within the Enterprise Developmental Framework.

In this article, I develop a refined framework that specifies six dimensions of Mindentity and integrates it into the Enterprise Developmental Framework.

From Thematic Enterprise to Anticipatory Cultural Sociology

This section outlines the developmental and activity-theoretical context in which the concept of Mindentity is situated.

On October 6, 2025, I released a five-stage Enterprise Development framework (see the diagram below).

- Creative Theme

- Scalable Focus

- Center Development

- Value Circle

- Developmental Platform

It roughly echoes the World of Activity model (also known as the Flow-Focus-Center-Circle schema), which was introduced in my first Kindle book, Homecoming: A Thematic Trip and the World of Activity Approach.

- Flow → Creative Theme

- Focus → Scalable Focus

- Center → Center Development

- Circle → Value Circle, Developmental Platform

Both the Enterprise Development framework and the World of Activity model are part of Creative Life Theory (v3.0).

The Enterprise Development framework curates several ideas I developed in previous book drafts over the past several years. More details can be found in a Tiny Paper published on Possible Press.

There are multiple ways to define the concept of enterprise. In my framework, I use the terms “Enterprise” and “Creative Enterprise” interchangeably. Theoretically, however, both refer to Thematic Enterprise, emphasizing that all enterprises are fundamentally thematic, centered around a guiding theme.

However, this perspective leaves open a key question: what is the ontological status of the thematic results that precede formal organization, institutionalization, or reward?

This core thematic orientation provides the unity across all enterprises, while different forms — Knowledge, Business, and Cultural — express this concept in distinct ways. They vary in terms of goals, participants, duration, and systemic organization, yet all remain linked by the central theme that ensures coherence across enterprises.

For example, the diagram below highlights the different purposes of three forms of enterprises:

- Knowledge Enterprise → Epistemic Impact

- Business Enterprise → Market Impact

- Cultural Enterprise → Social Impact

This model also indicates the three types of themes: knowledge themes, business themes, and cultural themes. While both are concept systems at the deep level, they appear as different thematic frameworks to guide their enterprises.

Based on the Flow-Focus-Center-Circle schema, I also developed the “Culture as Thematic Enterprise” Framework (see the diagram below).

The framework illustrates how individual creative exploration naturally evolves through stages: Creative Life (meaning discovery) → Tiny Culture (scalable focus) → Cultural Center (key function) → Cultural Movement. Each stage has independent value, with evolution happening organically rather than by design.

Two foundational elements support this process: Cultural Genidentity (essential differences + situational dynamics) and Double Curativity (curation commons) — ensuring both uniqueness and continuity across cultural forms.

On January 5, 2026, I curated the above frameworks with others together to form a new thematic enterprise: the “Anticipatory Cultural Sociology (ACS)” Framework.

In this new framework, the social world is understood as a nested AAS (Anticipatory Activity System), while Cultural development, in this view, is a continuous, dynamic anticipatory activity of creating and curating concept systems and transforming them into thematic enterprises by weaving active agency and evolving structure within the social world.

More details can be found in a thematic collection published on Possible Press.

This framework makes it necessary to clarify the status of early creative results that exist before they become enterprises — a gap addressed by the concept of Mindentity.

The First Principle of Thematic Creation

This article proposes a first principle of thematic creation:

All results of thematic creation exist first as Mindentities — prior to recognition, reward, or institutionalization.

This principle concerns the ontological status of creative results before they enter systems of exchange, evaluation, or formal organization. It addresses how an abstract theme first becomes real in the social world, independent of external reward.

Within the Anticipatory Cultural Sociology (ACS) framework, this principle can be formally located in the Anticipatory Activity System (AAS) model.

The AAS framework is structured around five pairs of concepts:

- Present — Future

- Self — Other

- Object — Objective

- Result — Reward

- First-order Activity — Second-order Activity

Among these, this article focuses specifically on the Result–Reward pair.

In the AAS framework, Result refers to the immediate outcome of creative activity, while Reward denotes external validation, exchange value, or institutional recognition. The concept of Mindentity is introduced to clarify the ontological status of Result prior to Reward.

All results of thematic creation exist first as Mindentities, without any external reward. Only later, by incorporating considerations of reward, can a Mindentity transform into an institutionalized entity, such as a product (commodity) or an organization (firm).

Before a creative work becomes a product or an organization, it exists as a Mindentity. Mindentity thus constitutes the ontological foundation through which a creator brings an abstract theme into the real world.

This is the First Principle of Thematic Creation. It provides a foundational lens for understanding how cultural innovation begins, prior to institutionalization, evaluation, or formal recognition.

The Mindentity Framework: Dual-Dimension of Results

Having established the First Principle of Thematic Creation, we now move one step further to develop a six-dimensional framework for empirical analysis and case studies.

The Mindentity framework bridges the internal world of the creator with the external ecological system. It conceptualizes creative results along two fundamental dimensions:

- The Subjective Dimension: Psychological Ownership

- The Objective Dimension: Ecological Objectification

Together, these dimensions describe how a Mindentity exists simultaneously as an internal possession of the creator and as an emerging object within the social-ecological world.

The Subjective Dimension: Psychological Ownership

The concept of psychological ownership originates in organizational behavior research, most notably articulated by Pierce, Kostova, and Dirks (2001). It refers to a psychological state in which individuals experience a sense that a target — material or immaterial — is “theirs,” independent of formal or legal ownership.

Psychological ownership is theorized to emerge through three primary routes: control over the target, intimate knowledge of it, and self-investment of time, effort, or personal resources. When these conditions are present, objects, spaces, or even abstract entities may become incorporated into an individual’s self-concept, producing a strong sense of possession in the absence of legal ownership.

Inspired by this theory, the Mindentity framework defines three subjective dimensions of results:

- Control: The creator retains exclusive authority over the direction, modification, and evolution of the object. Unlike a commercial entity constrained by contracts or governance structures, a Mindentity remains under the creator’s autonomous control.

- Intimate Knowledge: The creator holds a “God’s eye view” of the object, understanding its internal logic, developmental history, and latent possibilities — knowledge that cannot be fully transferred or codified.

- Self-Investment: The object becomes a container for the creator’s time, energy, experience, and data. It is not merely an output but a projection of the self, carrying traces of personal commitment and identity.

The Objective Dimension: Ecological Objectification

The objective dimension of Mindentity concerns how a creative result becomes objectified within the social-ecological world. This dimension is inspired by Hegel’s theory of the objectification of concepts, as interpreted by Andy Blunden, who distinguishes three forms of objectification: symbolic, instrumental, and practical.

Within the Mindentity framework, these forms are articulated as follows:

- Symbolic Objectification (Symbol): The process of naming. By assigning a name, concept, or visual marker to a vague theme, the creator renders it communicable and establishes it as a shared focus for action within a linguistic system (for example, coining the term “Mindentity”).

- Instrumental Objectification (Instrument): The creation of artifacts. The concept is reified into tangible or operational forms — such as documents, diagrams, software tools, or media objects — that enable interaction, use, and transmission.

- Practical Objectification (Practice): The embedding of the artifact into recurring social practices. Through repeated use, the instrument stabilizes into routines, niches, or micro-communities, forming a recognizable ecological presence.

Taken together, these six dimensions — three subjective and three objective — constitute a meaningful whole: a Minimum Viable Unit (MVU) of Thematic Creation.

A Mindentity reaches MVU status when psychological ownership and ecological objectification are both present, even in minimal form. At this stage, a creative result is neither purely internal nor fully institutionalized; it exists as a viable, developing unit capable of further social expansion.

Case Study: The “Possible Books”

Creative results often occupy a liminal space — neither entirely internal nor formally institutionalized. The Possible Book exemplifies this space, existing simultaneously as a personal creation and a social-ecological object.

I have been using the term “Possible Books” for many years. After publishing my 30th Possible Book on March 31, 2024, I realized I had completed a 5-year creative journey.

This insight inspired me to run a Creative Life Curation project in April 2024. I used the 30 Possible Books as raw materials to analyze patterns behind my journey. One of the models from this analysis is shown in the diagram below.

Additionally, I wrote a 100-slide deck in Chinese to tell the whole story of this creative journey. In May 2024, I shared the deck with friends in China. One friend sent me a list of interview questions, including one about Possible Books.

You refer to these manuscripts as “Possible Books” rather than official publications. What is the reason behind this? Do you have plans to convert these manuscripts into official publications, or do you prefer to maintain this exploratory form? Alternatively, will you share them for free as e-books?

I explained that I use Knowledge Projects as the basic unit of my creative journey, focusing on Connecting Theory and Practice, with Knowledge Frameworks as the primary output. These manuscripts are not my main outputs but rather creative containers that hold the outcomes of these knowledge projects and house the knowledge frameworks they produce.

These manuscripts are not created with the intent of formal publication. However, because they are over 250 pages long and more formal and rigorous in content than Notes, I refer to them as Possible Books.

From the perspective of Creative Life Theory, this is a unique Genre particularly useful for studying the Early Discovery phase of Creative Life.

Today, the “Possible Book” — a curated, 250+ page manuscript that has not been formally published — serves as an archetypal Mindentity.

Subjective Reality (Why it sustains me):

- Control: I decide the length, the cover, and the content without a publisher’s interference.

- Intimate Knowledge: I know the connection between every chapter and concept intimately.

- Self-Investment: The manuscript holds years of my articles and thoughts; it is a repository of my life’s labor.

Objective Reality (How it functions):

- Symbolic: Naming it “Ecological Formism (book, v1, 2025)” or “Castle and Forest: The Landscape of Concept-related Knowledge Engagement (book, v2.0, 2025)” gives it a social existence. It can be discussed.

- Instrumental: When articles are curated as a Possible Book, it becomes an instrument. Readers can access the outcome of a long-term knowledge project by reading a systematic introduction, key concepts, and diagrams. The detailed Table of Contents offers them a guide to dig deep to find relevant ideas in specific articles.

- Practical: These possible books create a niche. Even though unpublished by publishing houses, they establish my authority in a specific domain and create a small circle of feedback.

The “Possible Book” proves that a project does not need to be a Legal Entity or Institutionalized Entity to be real, viable, and valuable.

The “Tiny Culture (Mindentity)” Structure

Finally, we place Mindentity back into the macro-framework of “Culture as Thematic Enterprise.”

The framework illustrates how individual creative exploration naturally evolves through stages:

Creative Life (meaning discovery) → Tiny Culture (scalable focus) → Cultural Center (key function) → Cultural Movement

Each stage has independent value, with evolution happening organically rather than by design.

The Mindentity integrates into this framework through its pairing with Tiny Culture, forming a Container–Conteinee Structure.

- Tiny Culture (Mindentity)

Within the framework, Tiny Culture corresponds to Focus. The Tiny Culture (Mindentity) represents a dual-focus perspective:

- Creator: the Mindentity itself

- Suppter: the Tiny Culture that engages with it

Both operate within a shared Activity Circle (see diagram below).

The Creator produces the Mindentity, while the Supporter cultivates the Tiny Culture by interacting with it.

This specific Activity Circle reveals a fundamental dynamic in cultural formation:

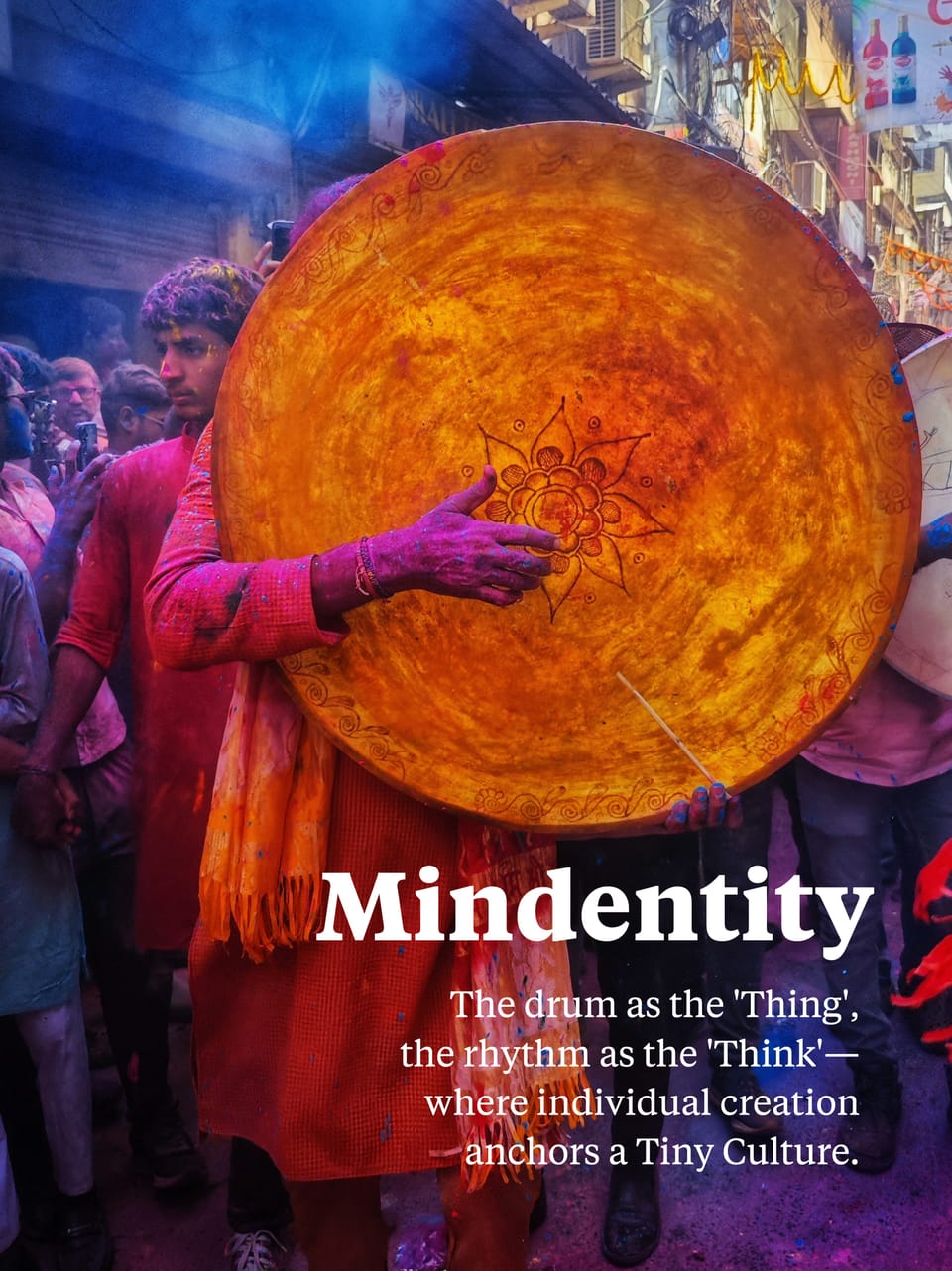

- The Mindentity serves as the “Thing”: a concrete anchor point, the Object around which social activity can coalesce. Without a Mindentity (whether it be a possible book, a software project, a theoretical framework, or an artistic creation), there is no tangible focal point for collective engagement.

- The Tiny Culture functions as the “Think”: the social consciousness that forms around the Mindentity. It emerges from the collective meaning generated by early supporters, contributors, and participants who recognize its value and invest their energy in engaging with, developing, and propagating it.

Together, this structure highlights how personal creative results (Mindentities) and emergent social consciousness (Tiny Culture) co-evolve, forming the building blocks of cultural formation.

Container-Containee: The Ontological Foundation

This brings us to the crucial insight about the Container-Containee relationship: without Mindentity, there would be no Tiny Culture. The Thing must precede the Think in ontological order. Cultural formation requires a tangible object around which social activity can coalesce. This is not merely a temporal sequence but an ontological necessity — the container (Tiny Culture) cannot exist without the containee (Mindentity).

However, this relationship is not strictly one-directional. While the Thing provides the necessary anchor, its development fundamentally relies on the nourishment of the Think. The Mindentity requires Tiny Culture to validate it, to test it, to translate it into more accessible forms, and to protect it during its vulnerable early stages. Creator and supporters engage in Co-becoming — a mutual evolution in which the Mindentity develops through interaction with its early community, while that community simultaneously cultivates its own identity, practices, and culture around the Mindentity.

By positioning Mindentity before Tiny Culture in the developmental sequence, we complete a crucial piece of the ontology of Thematic Enterprise. The Mindentity is the distinct object — the Result in the “Result–Reward” schema — that exists first without external reward, purely as a manifestation of the creator’s psychological ownership and ecological objectification. It marks the moment when creative intention becomes tangible reality and private vision attains its first form of public existence.

This is the First Principle of Thematic Creation: all results of thematic creation are Mindentity first. Before recognition, before reward, before legal status or institutional validation, the creative work exists as Mindentity — anchored in the creator’s psychological ownership (control, intimate knowledge, self-investment) and beginning its journey toward ecological objectification (symbolic, instrumental, practical).

The Tiny Culture then emerges as the first social container, enabling the Mindentity to transform from individual creation into collective culture. It provides the crucial middle layer — the “missing link” in traditional cultural sociology — between the isolated creator and larger social institutions. Through Tiny Culture, the Mindentity gains initial social validation, undergoes early testing and refinement, achieves its first translations into accessible forms, and receives the protection necessary for continued development.

Understanding this Container–Containee relationship is essential for grasping how cultural innovation functions in practice. It explains why some creations remain perpetually at the Mindentity stage (lacking social traction to generate Tiny Culture), why others successfully transition through Tiny Culture toward larger institutional forms (Cultural Center, Cultural Movement), and why some deliberately resist Entity-fication, preserving the flexibility and creative freedom of the Mindentity or Tiny Culture stage.

This framework thus provides not only a descriptive account of how thematic enterprises develop, but also a normative tool for creators to understand their choices: when to remain in the realm of Mindentity and psychological ownership, when to cultivate a Tiny Culture, and when (if ever) to pursue the external rewards and formal recognition that come with Entity status.

This framework thus offers not only a descriptive account of thematic enterprise development but also a normative guide for creators: when to remain within Mindentity and psychological ownership, when to cultivate a Tiny Culture, and when (if ever) to pursue external rewards and formal recognition that come with Entity status.

v1.0 - January 26, 2026 - 2,932 words