Revisiting the "Activity - Relation" Framework (2017)

Deconstructing Oliver Ding's "Activity as Container" Conceptual Deck

by Oliver Ding

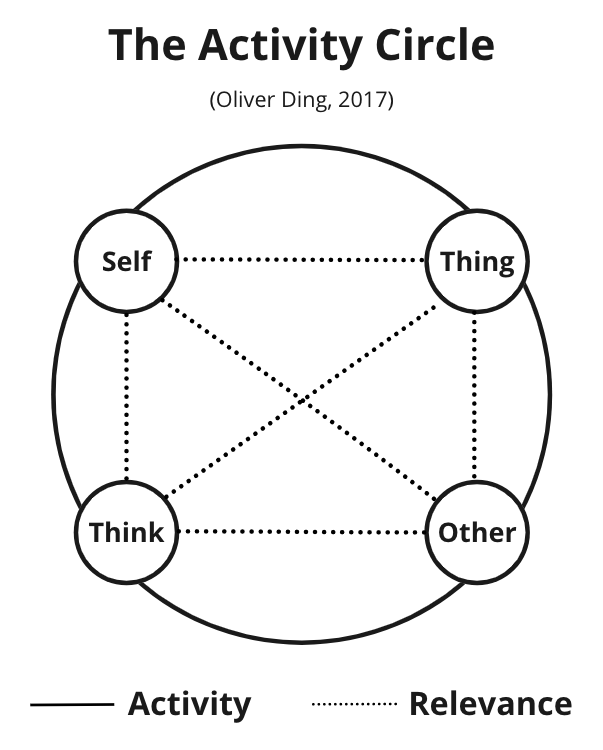

In 2017, I wrote a conceptual deck to introduce my ideas about the "Activity as Container" perspective, resulting in the "Activity - Relation" Framework, which is the seed of the Activity Circle Model.

The original conceptual deck was written in Chinese. Last week, I asked AI to write a report to introduce the framework in English. Today, I shared what Google Notebook LM wrote below as a reference to see my early ideas.

An Analytical Framework for Activity and Relation: Deconstructing Oliver Ding's "Activity as Container" Perspective

by Google Notebook LM

1.0 Introduction: The Narrative of the Piano House

On the afternoon of August 26th, Oliver Ding and his son, Peifeng, found themselves with a few minutes to spare in the waiting room of a piano school. Peifeng, carrying a LEGO transformer, began to play with a music stand, flipping it around and discovering its affordances. He placed his toy on the stand, turning it to face his father as if on a miniature stage. Ding responded with encouraging facial expressions, and an emergent game was born. Peifeng experimented with different poses for his transformer, and Ding escalated the play by covering his eyes, asking his son to set up a new "scene" and call out when he was ready for the reveal.

A week later, on September 2nd, the scene repeated itself. Father and son were once again in the waiting room, but this time, Peifeng had not brought his LEGO toy. Undeterred, upon entering the room, he immediately declared, "Let's play the guessing game!" He instructed his father to cover his eyes, and using his own body along with a nearby chair, he began creating poses for his father to guess. The game had evolved, its core identity persisting even as the objects and specific actions changed.

This seemingly simple interaction poses a significant challenge for mainstream theories of human activity. Goal-oriented frameworks such as classical Activity Theory struggle to account for the value of the non-instrumental, emergent "guessing game," while purely environmental theories like Ecological Psychology may overlook the active, creative agency of the participants. This highlights a need for an integrated framework that can synthesize subject-driven agency with environment-driven structure. How, then, can we systematically analyze and understand the rich, emergent, and meaningful interactions that constitute our daily lives?

Oliver Ding's "Activity as Container" conceptual deck (2017) offers a novel framework for this purpose, providing a series of analytical lenses to deconstruct the complex fabric of human relationships as they unfold within the activities of our lives. This document will explore his framework in detail. The Piano House narrative reveals interactions that are both structured by their context and creatively emergent within it. To analyze this duality, we need a core metaphor that can account for both boundary and potential—a role Ding assigns to the "Container."

2.0 The "Container" Metaphor: A New Lens for Activity

To understand the relationships that form within and through our activities, we must first establish a core conceptual metaphor. Oliver Ding proposes the "Container View" (容器观) as this foundation. The central idea is that activities themselves are containers for relationships, shaping the interactions that occur within them. This metaphor allows us to move beyond a simple description of actions to a deeper analysis of the environment, meaning, and boundaries that define an experience. This section will unpack the key components of this powerful metaphor.

2.1 The Essence of the Container View

The Container View is built upon a dual perspective that integrates a first-person "experience" with a third-person "analysis".

- Situatedness (置身所在): This is the first-person perspective of direct experience. It emphasizes the intuitive, embodied understanding we gain by being in a situation. In this view, the "container" (容器) is the object or activity (a family, a project, a relationship), and the "containee" (容物) is the subject—the person situated within it.

- Action Reflection (行动反省): This is the third-person perspective of the observer. It allows the subject to step back and analyze their own experiences and interactions. From this viewpoint, both the container and the containee become objects of reflection and analysis.

This dualism is central to the framework, allowing for a model that honors the richness of lived experience while providing the structure needed for rigorous analysis.

2.2 Core Concepts of the Container View

The Container View is defined by three interrelated core concepts that describe the dynamics between the container and the person within it.

- Containability (可容性): Ding introduces this term to describe the primary potential an activity-container offers to the person inside it. It is derived from, but intended to expand upon, Ecological Psychology's concept of "Affordance." The theoretical necessity for this new term arises from the limitations of Affordance, which is an eco-physical theory ill-suited for analyzing "social containers" (like an organization) or situations involving "dual subjectivity" (where the container itself is an active agent). "Containability" is proposed as a more flexible concept that emphasizes a reciprocal mechanism; it is not just a property of the container, but a relational potential that emerges from the interaction between the container and the unique characteristics of the contained entity.

- Life Stream (生命流): The human being, as the "containee" entity, experiences life as a continuous flow—a "Life Stream"—that moves through various containers. This concept, inspired by Henri Bergson's philosophy of "duration" (绵延), views life as an authentic, unbroken whole. However, social structures and objective containers (like projects, meetings, or social roles) often break this flow into discrete segments, a process Ding terms "fragmentation" (碎化).

- Interaction Boundary (互动边界): Every container, by its nature, defines the boundaries of an interaction. These boundaries are not merely physical; they manifest across multiple dimensions, including time (a project deadline), space (a physical office or a digital chatroom), content (the topic of a meeting), and even hierarchy. These boundaries shape the flow of resources, establish order, and define the field in which relationships develop.

The abstract concept of the "Container" provides the theoretical lens, which must then be applied to the concrete unit of analysis where life is actually lived: the "Situational Event."

3.0 Deconstructing the Situational Event: The Building Blocks of Interaction

The Container View is not merely an abstract philosophy; it is an analytical tool applied to the tangible moments of life. Ding terms these moments "Situational Events" (情境事件) to distinguish them from larger, indirect "historical events." A situational event is the context in which relationships become real and observable. This section will break down the structure of these events into their fundamental components, providing the analytical tools necessary to apply the framework.

3.1 The Scene (现场): The Locus of Direct Influence

The starting point for any analysis is the "Scene" (现场), a concept adapted from Kurt Lewin's "principle of contemporaneity." The Scene is defined by what has a direct influence on the participants at that moment.

- Inside the Scene: People, objects, and information that are immediately present and directly impacting the interaction.

- Outside the Scene: Past events, future plans, or absent individuals that may have an indirect influence through memory, imagination, or reasoning, but are not part of the immediate context.

Critically, a Scene is not limited to physical space. It can seamlessly encompass both physical and digital environments. For instance, a person on a video call in a park is simultaneously in the physical scene of the park and the digital scene of the call. The analysis focuses on the combined "Scene" where the direct interaction occurs.

3.2 The Anatomy of an Event

Ding proposes a hierarchical structure for analyzing the temporal flow of any situational event.

- The 3E Structure: At the highest level, any event can be broken down into three phases: Enter (the beginning), Event (a series of Episodes), and Exit (the conclusion).

- Main vs. Side Episodes (骨干与侧翼事段): This distinction is a critical theoretical innovation designed to resolve a key limitation of goal-oriented frameworks.

- Main Episodes are activities that align with the pre-established goal or primary purpose of the event. In the Piano House case, the Main Episode is the piano lesson itself.

- Side Episodes are emergent, often unintentional actions that are not aligned with the main goal. The play that unfolded in the waiting room is a classic Side Episode. While goal-oriented theories like mainstream Activity Theory struggle to account for such moments, Ding's framework gives them a formal place, recognizing them as fertile ground for creativity, learning, and relationship-building.

- The Unit of Interaction - Moves (举动): To analyze the micro-dynamics of an interaction, Ding introduces the "move" as the most granular unit, inspired by turn-taking in games like chess. This unit is designed to capture social interaction, a level of analysis finer than the task-oriented "operation" in Activity Theory.

- Initial Move (启手): An action initiated by one party. The term is deliberately chosen for its dual meaning: for the initiator, it is a "start" (启动), but for the respondent, it can be an "inspiration" or "enlightenment" (启迪), opening up new possibilities for action. This duality synthesizes the active and passive perspectives within the interaction.

- Follow Move (跟手): The response from the other party. This is not necessarily a passive reaction; a Follow Move can be a simple act of following, a pause (buffering), or a creative pivot that redirects the interaction.

- Round (回合): The combination of one Initial Move and one Follow Move constitutes a single Round of interaction. An episode is composed of one or more rounds.

3.3 The Piano House, Re-examined

Applying this structural analysis to the first Piano House interaction makes the concepts concrete. The event on August 26th can be deconstructed as follows:

Analytical Level | Description of Interaction (August 26th) | Analysis / Implication |

Event | Oliver Ding takes his son, Peifeng, to his weekly piano lesson. | The overarching goal-oriented activity that provides the context. |

Main Episode | The piano lesson itself (taking place in the other room). | The planned, goal-aligned portion of the Event. |

Side Episode | An emergent game of "miniature stage" that occurs in the waiting room. | A non-goal-oriented interaction that enriches the relationship. The framework gives this equal analytical weight. |

Round 1 | Initial Move (Peifeng): Places his LEGO on the music stand and turns it toward his father. | Establishes a shared object of attention and initiates a non-verbal bid for interaction. |

Follow Move (Ding): Responds with encouraging facial expressions. | Accepts the bid and validates the son's creative action, creating a space for further play. | |

Round 2 | Initial Move (Peifeng): Continues the play by creating new and varied poses with the transformer. | Builds upon the established interaction, exploring the possibilities within the newly created game frame. |

Follow Move (Ding): Escalates the game by covering his eyes and asking for a "scene." | Transforms the play from simple observation into a structured game and establishes a repeatable routine. |

This detailed breakdown shows how the framework deconstructs both the planned and unplanned dimensions of an interaction. Now that these structural building blocks are established, we can use a set of integrated analytical lenses to understand the deeper relationships they form.

4.0 The Five-Aspect Analytical Framework

At the heart of Ding's theory is a five-aspect framework for analyzing activity and relation. These aspects are not a rigid, nested hierarchy but a series of interconnected analytical lenses that can be applied to any situational event to reveal different facets of the interaction. Together, they form an integrated system for describing part-whole relationships, the influence of the environment, the dynamics of boundaries, and the persistence of identity over time.

4.1 Aspect 1: Theme (主题) - The Search for Meaning

The "Theme" acts as a mediator of meaning within an event, allowing participants to perceive a series of actions as a coherent whole. Themes are constructed through the perception of Similarity between actions and made meaningful through Relevance (temporal, spatial, motivational, or causal).

A theme can be explicit, as in the designed theme of a conference (Design Theme) or the culturally understood theme of a wedding (Native Theme). It can also be implicit, requiring interpretation, especially in emergent Side Episodes.

This aspect provides the answer to "what is this event about?" which in turn shapes the part-whole analysis of its Composition.

4.2 Aspect 2: Composition (组合) - The Part-Whole Experience

Inspired by John Dewey's "compositional thread," this level analyzes the part-whole relationships that structure an experience. An activity is always a composition of smaller elements, and this analysis considers three primary types: the combination of Objects, People, and Events. The intentional act of creating such compositions is "Curation" (集展).

This aspect examines how the elements identified via the structural analysis in Section 3.0 are assembled to form the coherent whole perceived in Theme (Aspect 1). The way these parts are assembled is, in turn, enabled or constrained by how they are spread across the environment, which is the focus of the next aspect.

4.3 Aspect 3: Distribution (分布) - The Interplay of Inside and Outside

Drawing from Edwin Hutchins' theory of Distributed Cognition, this level examines how cognitive and practical activities are distributed across a system. It details the relationship between what is "inside the scene" and "outside the scene," analyzing three key forms of distribution: Social (across people), Spatial (between internal and external representations), and Temporal (between process and history).

This lens reveals the broader network in which an activity's Composition (Aspect 2) is embedded, showing how resources and knowledge flow across time and space to make the event possible. The efficiency of this distribution is often determined by the permeability of the system's boundaries.

4.4 Aspect 4: Openness (开放) - The Dynamics of Boundaries

This level analyzes the permeability of the boundaries of an activity's core elements, determining who and what can enter the system. The degree of openness shapes participation, learning, and the flow of resources analyzed in Distribution (Aspect 3).

- Openness of People: Relates to the "Openness to experience" personality trait.

- Openness of Events: Refers to the spectrum of participation formats, from controlled to open (e.g., TEDx).

- Openness of Objects: Describes "open tools" where one person's use is observable and understandable to others, facilitating collaborative learning.

An activity's degree of openness determines its potential for change, which stands in dynamic tension with the core identity that persists through that change.

4.5 Aspect 5: Genidentity (基识) - The Duality of Change and Invariance

Aspect 5, Genidentity, provides the longitudinal anchor for the entire framework. Borrowed from Kurt Lewin's 1922 paper The Concept of Genesis in Physics, Biology and Evolutional History, "Genidentity" refers to the essential identity of a thing that persists through transformation over time. It is the conceptual opposite of Affordance; it forces the analyst to consider not just what an activity can become, but what it essentially is.

It is the Genidentity of an activity (e.g., "payment," "meeting") that defines its core Theme (Aspect 1), which persists even as its material Composition (Aspect 2) and social Distribution (Aspect 3) evolve. The "guessing game" in the Piano House retained its Genidentity despite a change in objects, demonstrating the persistence of an activity's core essence.

Having detailed this integrated framework, it is important to situate it within the broader landscape of academic thought by comparing it to its most prominent predecessor.

5.0 Comparative Analysis: A Dialogue with Mainstream Activity Theory

While Oliver Ding's framework draws inspiration from historical-cultural Activity Theory (AT), it represents a significant departure in its focus, structure, and analytical power. This comparison is not merely academic; it highlights the specific theoretical problems the "Activity Container" model is designed to solve, particularly in analyzing the fluid and emergent nature of everyday life.

5.1 Core Tenets of Leontiev's Activity Theory

Classical Activity Theory, developed by Alexei Leontiev, is defined by a rigid three-level hierarchical structure. Each level of human practice is nested within the one above it and is driven by a distinct psychological regulator.

Level of Practice | Psychological Regulator |

Activity | Motive (Why?) |

Action | Goal (What?) |

Operation | Conditions (How?) |

In this model, an Activity (e.g., getting an education) is driven by a long-term Motive. It is realized through a series of goal-directed Actions (e.g., attending a lecture), which are in turn carried out through automated Operations (e.g., typing notes) that adapt to specific Conditions.

5.2 Key Differentiators of the "Activity Container" Framework

The "Activity Container" framework differs from classical AT in several fundamental ways, each resolving a perceived limitation in the older model.

- Hierarchy vs. Analytical Layers: Ding's hierarchical structure of Event (情境事件) – Episode (事段) – Move (举动), developed within the "Activity as Container" perspective, is explicitly designed to overcome key limitations found in the strictly nested hierarchy of Classical Activity Theory (AT). The central difference lies in how each model handles intentionality, contingency, and the micro-level units of action in daily life. For AT, all major levels are strictly goal-directed and driven by motive (Activity) or goals (Action). Ding's structure establishes Differentiated Intentionality: a. Event (Macro): Must be goal-directed and intentional. b. Episode (Meso): Is not necessarily goal-directed; subjects can have no intention for certain episodes to occur. This allows the framework to integrate and explain unintentional or emergent activities (like "Play"), resolving the theoretical dilemma caused by AT’s insistence on goal-driven behavior.

- Handling Emergence: A significant limitation of AT is its strong goal-orientation, making it difficult to account for spontaneous or non-instrumental behaviors. Ding's framework explicitly solves this problem. First, the concept of Side Episodes gives formal analytical status to emergent interactions like the "Piano House" game. Second, it introduces "Play" (玩) as a core activity form defined by its low goal-orientation and immersive quality, recognizing it as a crucial engine for creativity and exploration that would be dismissed as noise in a strict AT analysis.

- Unit of Analysis: The most granular unit in AT is the task-oriented "Operation." Ding's framework drills down further to the interaction-oriented "Move" (Initial Move and Follow Move). This theoretical shift from a unit of task-execution to a unit of social interaction makes the "Activity Container" model far better suited for the micro-level analysis of relationships and turn-by-turn dynamics between people.

- Integration of Perspectives: Ding's framework is an explicit attempt to synthesize two major theoretical traditions. It integrates the "active perspective" of AT, which emphasizes the subject's intentions and goals, with the "passive perspective" of Ecological Psychology, which emphasizes how the environment shapes and constrains behavior. Concepts like "Containability" and the central focus on the "Scene" create a more holistic model that accounts for both the subject's agency and the powerful influence of the environmental context.

This theoretical dialogue reveals that Ding's framework is not merely an extension of AT, but a reconceptualization aimed at creating a more versatile tool. We now turn to how this tool can be applied.

6.0 Application and Future Prospects

The ultimate value of a theoretical model lies in its application—to generate new insights, guide reflection, and inform creation. The Activity-as-Container framework is designed not only as an academic construct but as a practical set of tools for navigating personal and professional life. This final section explores its potential in the domains of research, personal reflection, and design.

6.1 The Framework for Research and Reflection

The model offers a dual utility, serving as a powerful lens for both formal research and personal sense-making.

- As a Research Framework: The three-level and five-aspect analysis and detailed breakdown of events provide a robust methodology for academics. Instead of general observation, it allows for highly specific inquiry. For instance, a researcher in learning sciences could ask: In a collaborative classroom project (the Event), how do emergent "Side Episodes" of peer-to-peer tutoring contribute to the "Social Distribution" of knowledge, and how does the "Openness" of the digital tools used either facilitate or hinder this process? This precision enables nuanced case studies in fields from organizational behavior to design research.

- As a Reflective Framework: On an individual level, the concepts offer a rich vocabulary for personal growth. An individual can use the idea of "Life Themes" to reflect on their career path, identifying recurring patterns by extracting "Side Episodes" from different jobs to construct a more authentic narrative of their passions. Practical tools like the Workline—a simple method for logging and analyzing daily events—provide a structured way to capture life's flow, enabling deeper reflection on personal productivity, relationships, and emotional patterns.

6.2 The Framework for Design

Perhaps the framework's most powerful application lies in the act of creation. Its principles are not just for analysis but for synthesis—for the intentional design of better human experiences. Designers, managers, educators, and community organizers can use these concepts to shape environments and activities that foster more positive and productive outcomes.

For example, a manager could design a team project not just by defining goals (the Main Episode), but by intentionally creating spaces and opportunities for informal interaction (fostering creative Side Episodes). A user experience designer could evaluate a digital tool using "Openness" as a heuristic, asking if it facilitates learning and collaboration among users. An educator could structure a curriculum as a "Composition" of different "Events" (lectures, workshops, field trips) designed to build toward a coherent thematic understanding. By consciously designing the "container," we can influence the quality of the relationships and experiences that unfold within it, encouraging creativity, strengthening collaboration, and shaping a more constructive culture.

The framework's forward-looking potential lies in this shift from merely understanding the world to providing the conceptual tools for actively designing it better.

7.0 Conclusion

Our lives are a tapestry woven from countless interactions, unfolding within the activities that give our days structure and meaning. From a simple game in a waiting room to a complex collaborative project, these "situational events" are the containers in which our relationships are formed, tested, and strengthened. Yet, traditional analytical models, with their rigid hierarchies and goal-oriented focus, often fail to capture the emergent, creative, and deeply personal nature of these everyday experiences.

Oliver Ding's "Activity as Container" framework offers a comprehensive and accessible alternative. By establishing the "Container" as a core metaphor, it provides a powerful, multi-layered framework for deconstructing the fabric of human interaction. Its structural components—from the overarching "Scene" down to the granular "Move"—allow for a precise analysis of an event's anatomy. The five interconnected analytical lenses of Theme, Composition, Distribution, Openness, and Genidentity equip us with a rich vocabulary to explore meaning, part-whole dynamics, environmental influence, and the interplay of change and persistence.

Moving beyond the limitations of its predecessors, the framework makes a unique contribution by explicitly accounting for emergent phenomena and synthesizing subject-driven and environment-driven perspectives. Ultimately, Ding's framework is more than an academic exercise; it is a practical toolkit for navigating, understanding, and, most importantly, designing the complex world of human relationships as they manifest in the containers of our daily lives.

v1 - December 15, 2025 - 3,943 words