The Concept of "Developmental Project"

The Living Way of the “Developmental Project” Concept

by Oliver Ding

Several months ago, I travelled to China, spending most of my time in Fuzhou. One day, after meeting a friend, I returned home and was told that the children were playing at a nearby community park. I decided to go there. At first, I assumed the park would be unremarkable, but to my surprise, it contained a large lotus pond. About a third of the water was covered with lotus leaves, dotted with blooming lotus flowers.

Seeing this familiar yet beautiful scene, I suddenly recalled that lotus ponds, leaves, flowers, and seeds were cherished memories from my childhood — details I had never fully noticed before.

Before the trip, I had drawn on the diagram of the Nine Aspects of Strategic Agency to develop a metaphor called the Flower of Heart-Mind, which I later incorporated into the World of Activity Approach. This set of objects — the pond, leaves, flowers, and seeds — became a metaphor that deepens the idea of the Flower of Heart-Mind blossoming within the World of Activity.

In this metaphor:

- The lotus pond represents the environment in which an actor is situated.

- Lotus leaves represent the support systems embedded in that environment.

- The lotus flower represents the actor’s mind and agency.

- Lotus seeds symbolize the outcomes of action and creation.

The blossoming of the heart-mind in the World of Activity depends on the freedom to unfold within that world. Openness of the environment, unfolding of agency, and blossoming of the heart-mind interact in subtle ways, and their interplay can give rise to moments of joy and positive experience.

After returning to Houston, I applied this ecological metaphor to design a thematic card illustrating the nine aspects of strategic agency. I am now using it in a new book draft, Developmental Projects: The Project Engagement Approach to Adult Development. Within this new context, the metaphor maps onto key concepts in Developmental Projects:

- Lotus flower: Corresponds to Theme in the Developmental Project Model, guiding the three elements of Developmental Resources. The visible, beautiful blossom mirrors how the Theme is the most salient and appealing part of a project.

- Lotus leaf: Corresponds to Identity. Each leaf has its own shape and position, reflecting its “identity” and governing the three elements of the Situational Context.

- Lotus seed: Corresponds to Project Outcomes and the Enterprise generated across a series of projects. Seeds mark both an ending (the flower fades) and a beginning (new life). When a seed falls into the mud, it grows into a new lotus, forming a cycle. Likewise, one project’s outcome can give rise to new projects, eventually developing into an enterprise.

- Lotus rhizome: Represents the Network of developmental projects. Hidden underwater, the rhizome connects different flowers, forming a network. Though invisible, it is essential for connection and resource flow.

- Lotus pond: Represents the broader Social Context in which developmental projects are embedded.

Moreover, this ecological metaphor reveals the living nature of the “Developmental Project” concept, which itself is like a lotus flower, blossoming within its environment. Originally, the concept was tied to the Developmental Project Model — a foundational framework of the Project Engagement Approach, first introduced in 2021. Since then, it has been applied across a series of knowledge projects in diverse contexts, linking to a range of related concepts. This ongoing evolution has expanded both its meaning and its significance, especially in its “developmental” dimension, an aspect that was largely overlooked in the early stages.

This article traces the evolving journey and broader conceptual landscape of “Developmental Projects,” while presenting a toolkit that bridges the Project Engagement Approach with the field of adult development, thus laying the groundwork for a potential new book.

Content

Part 1: The Journey

1.1 Engaging with Andy Blunden’s Ideas (2020)

1.2 Introducing the “Developmental Project” Concept (2021)

1.3 The Creative Swapping Moment (2025)

Part 2: The Landscape

2.1 Lotus Pond: Adult Development

2.2 Lotus Flower: Six Themes

2.3 Lotus Leaf: A Way to Shape Creative Identity

2.4 Lotus Seed: Container Z

2.5 Lotus Rhizome: Creative Enterprise

Part 3: Grasping the Concept

3.1 The Life Discovery Project (Spatial Dimension)

3.2 GAP Projects (Temporal Dimension)

3.3 The Mapping Strategic Moves Project (Integrative Dimension)

Part 4: Reclaim the Vision

4.1 Project as a Unit of Activity and Human Science

4.2 A Project is a Concept of Both Psychology and Sociology

4.3 Identity is a Collaborative Project

4.4 Project as Formation of Concepts

4.5 Social Group as Product of Projects

Part 1: The Journey

The “Developmental Project” concept has a history. It was not born fully formed but emerged gradually through a series of knowledge projects between 2020 and 2025.

This part traces that journey: from my initial engagement with Andy Blunden’s interdisciplinary approach to Activity Theory in 2020, to the naming of the Developmental Project Model in 2021, and finally to the Creative Swapping moment in 2025 that shifted my focus from “Project” to “Development.”

Understanding this journey reveals how theoretical concepts themselves develop through practice — a living demonstration of the very ideas explored here.

1.1 Engaging with Andy Blunden’s Ideas (2020)

The Project Engagement Approach was born from my journey of engaging with the tradition of Activity Theory, especially Andy Blunden’s approach to an interdisciplinary theory of Activity.

I began studying Activity Theory around 2015. In 2020, I worked on the Activity U project (phase I), resulting in two book drafts and the initial development of the Project Engagement approach.

The Activity U project officially began on August 19, 2020. Initially, I created a diagram called “Activity U,” which served as a test of the “HERO U” framework. I wrote a post explaining the diagram, and later expanded this post into a series of articles. These articles were eventually edited into two book drafts.

On December 8, 2020, I edited the first version of a book draft Activity U: How to think and act like an activity theorist. On January 24, 2021, I edited Project-oriented Activity Theory. Then, on February 3, 2021, I published the Project Engagement Toolkit (2021).

In the introduction to Project-oriented Activity Theory, I reviewed Blunden’s ideas, describing how I engaged with and further developed them.

Blunden suggested that:

- We can use “Project” as a new unit of analysis for Activity Theory.

- A Project should be understood as a “Formulation of Concepts.”

- The archetypal unit of “Project” is two people working together on a common project.

Blunden doesn’t use “Project-oriented Activity Theory” as an official name for his approach. Originally, I used this term to refer to Blunden’s approach. Later, I realized the term could be misleading because my articles present my interpretation of Blunden’s approach. Thus, I used it to refer to the whole account, initiated by Blunden, but also incorporating other people’s interpretations and applications.

Developing a new theoretical approach takes time. As Blunden pointed out, “…But it is early days. This book marks only the very first effort” (2014, p. 370). Moreover, it takes a village to raise a child: the development of a theoretical approach is a collaborative project, and more people are needed to echo Blunden’s vision.

The following list clarifies the distinctions between Blunden’s original approach and my interpretation:

- I designed a series of diagrams to illustrate Blunden’s approach.

- I added Projectivity and Zone of Project as two theoretical concepts to the original framework. Some of the theoretical resources behind these concepts were drawn from Ecological Psychology.

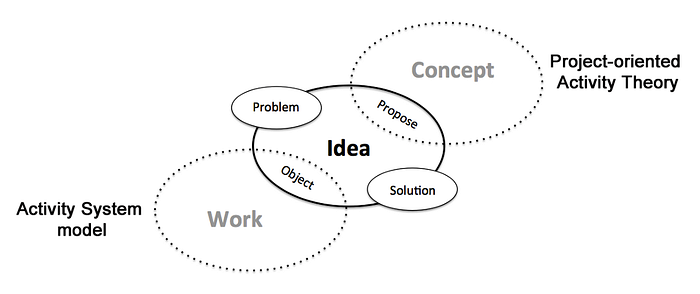

- I distinguished between Idea and Concept in order to reserve the term “Project” for normal works and social movements, noting that Blunden tended to emphasize Projects as (micro) social movements.

- Blunden’s original approach did not adopt the Activity System model. I claimed that it was possible to keep Blunden’s approach and the Activity System model together within a theoretical framework by distinguishing between Idea and Concept. In this manner, we could grow Activity Theory without discarding the Activity System model, since it was an established branch of Activity Theory.

- Based on the concept of Projectivity, I developed a model called Cultural Projection Analysis.

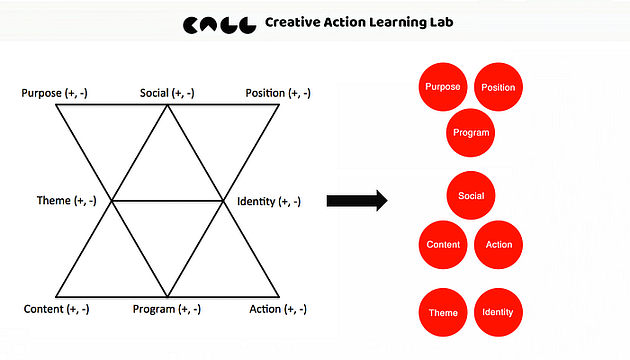

- I find a connection between my own idea Themes of Practice and Blunden’s Formation of Concept. I consider Theme as a special type of Concept. Based on Formation of Concept, I applied Themes of Practice to analyze the internal structure and dynamics of Projects. In particular, I identified five Themes of Practice of Projects: Idea, Resource, Program, Performance and Solution.

- I connected my idea of Ecological Zone with Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development. I also noted that Blunden described an archetypal unit of a Project as two people working together in a common project (2010, An Interdisciplinary Theory of Activity). By curating these ideas together, I developed a new concept of Zone of Project, which expanded on Blunden’s archetypal unit.

- I introduced Impact Projects and Serial Creators as intermediate concepts to bridge theory and practice, particularly for studying knowledge work and the development of knowledge workers.

The most important difference between Blunden’s original approach and my interpretations was that his vision aimed to develop a general interdisciplinary theory of Activity as a meta-theory, whereas my vision was to adopt his meta-theory and develop frameworks and models for practical studies. My focus was on knowledge work and knowledge workers, while Andy Blunden’s interest lay more in social movements.

Although Project-oriented Activity Theory (2020) and the Project Engagement Toolkit (2021) laid the foundation for the Project Engagement Approach, the concept of the “Developmental Project” had not yet been born.

1.2 Introducing the “Developmental Project” Concept (2021)

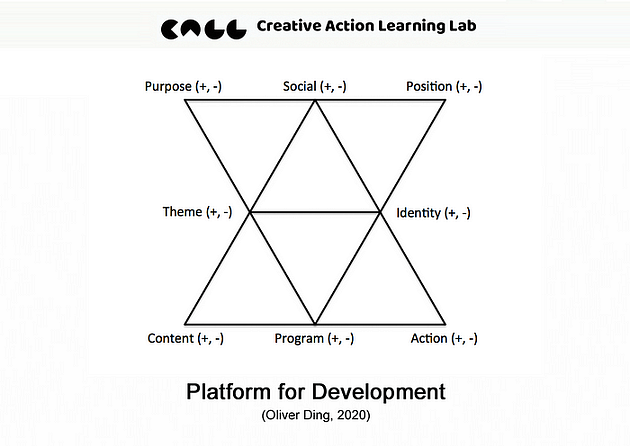

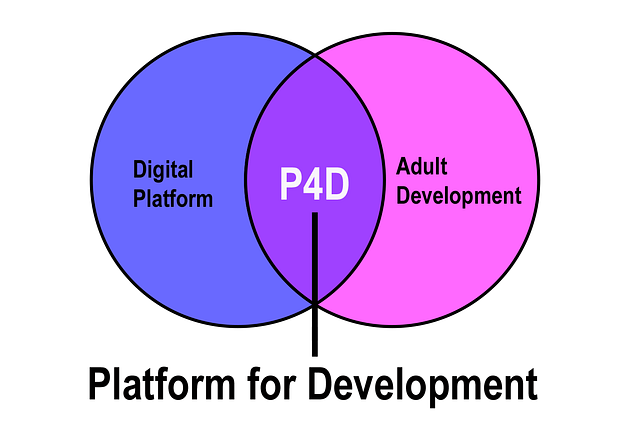

On December 13, 2020, I published an article titled The Platform for Development (P4D) Framework (v1.0). The P4D framework is a platform-based project-oriented activity-theoretical approach. The core of the framework is Platform[Project(People)], which defines a nested social structure for understanding the transformation of individuals and society.

The major theoretical resources behind the framework are Activity Theory (the project-oriented approach, Andy Blunden, 2014), Social Domains Theory (Derek Layder, 1997), Ecological Psychology (James Gibson, 1979), and Self-Determination Theory (Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, 1971, 2017). I was also inspired by Knud Illeris’ How We Learn (2007) and John Hagel’s The Power of Platform (2015).

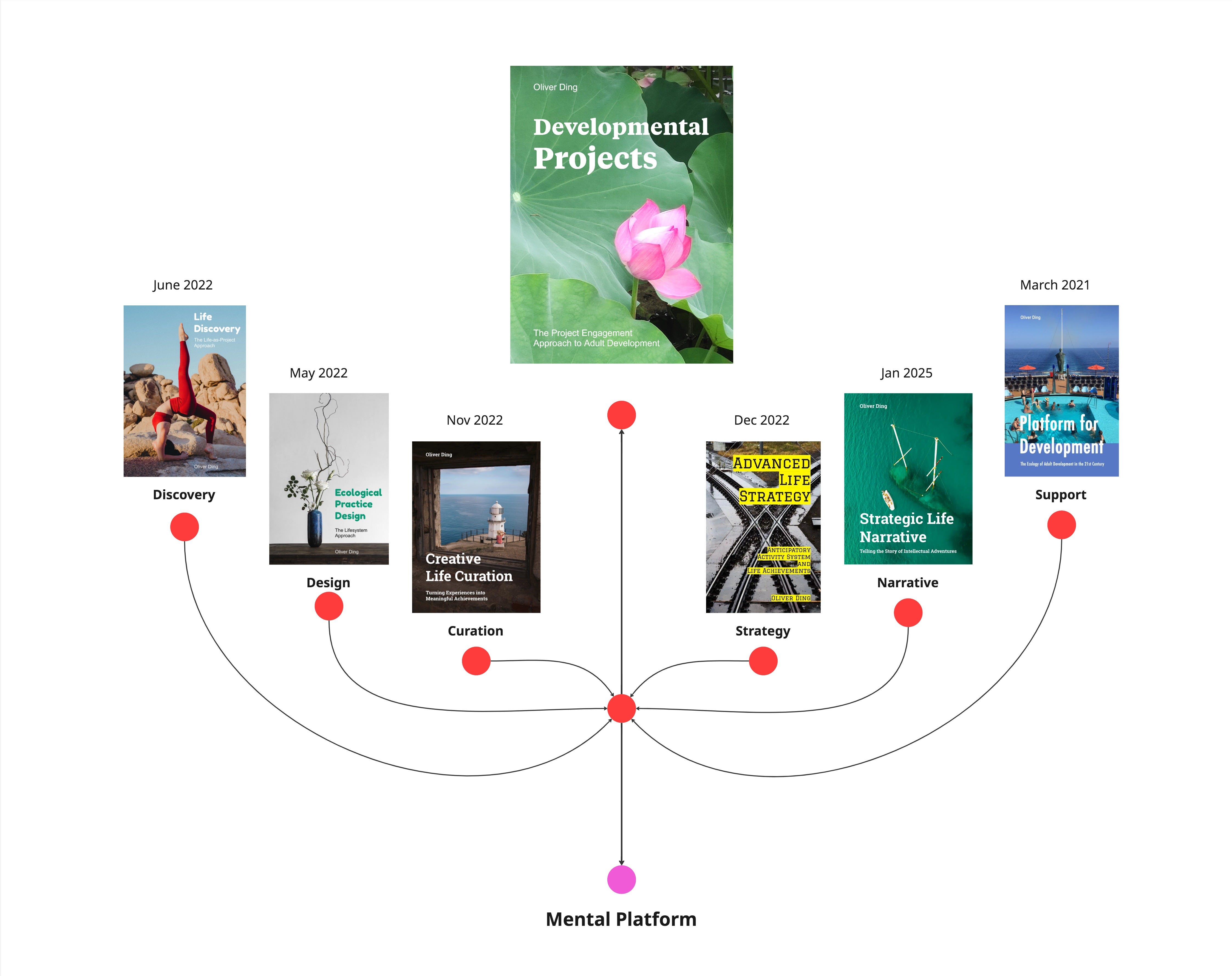

Later, I expanded the P4D to v2.0 with a new book draft: Platform for Development: The Ecology of Adult Development in the 21st Century. However, the book is not about Activity Theory, but the ecological practice approach. Thus, I renamed the P4D (v1.0) to the Developmental Project Model on March 31, 2021.

More details can be found in The Developmental Project Model (Archived).

Why did I name the model “Developmental Project”? I did not explicitly write out my reasons, but a possible explanation is that it was born from the Platform for Development project, which introduced the “Developmental Platform” concept as a core idea of the approach.

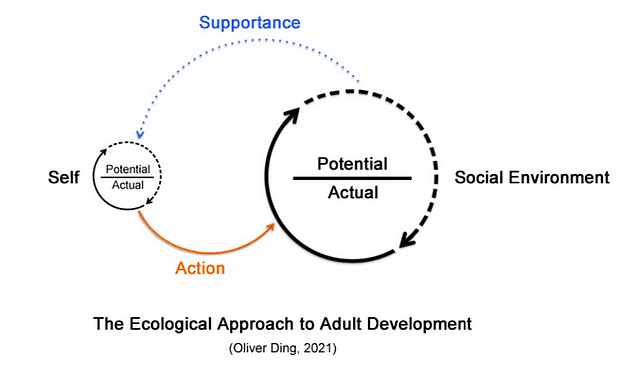

In Platform for Development, based on Lev Vygotsky’s ideas, I developed an ecological approach to adult development. The concept of “Developmental Platform” was introduced as a special type of social environment for this new approach.

When renaming the Platform for Development model (v1.0, 2020) to the Developmental Project Model, I may have thought that these two concepts formed a series for the ecological approach to adult development. However, this connection was not clearly articulated in the article and may only appear in later work.

From 2021 to 2024, I did not develop the “Developmental” aspect of the “Developmental Project” concept. In other words, the concept functioned mainly as an operational label for the Developmental Project Model. During this period, I developed three versions of the Project Engagement Approach, but the “Developmental Project” concept was not yet developed as a key theoretical concept exploring the “Developmental” aspect of project engagement.

1.3 The Creative Swapping Moment (2025)

On November 12, 2025, I published a long article on the Creative Identity Engagement Framework, which is part of the Project Engagement Approach (version 3.1).

On November 15, 2025, I wrote and sent out the newsletter of the Activity Analysis Center. In that issue, I shared an idea for a new project:

After publishing the article, I began considering whether it was time to edit a new book draft titled Developmental Projects: The Project Engagement Approach to Adult Development. Over the past several months, I have written multiple long articles exploring themes, identity, and enterprise, all deeply related to adult development. I have also conducted several case studies on gap projects, discovering several patterns. It is now time to curate these articles together to present these new developments.

The following day, I officially started the new project and designed a cover image for the possible book.

The project guided me to review the historical development of the Project Engagement Approach and my creative journey with development-related projects.

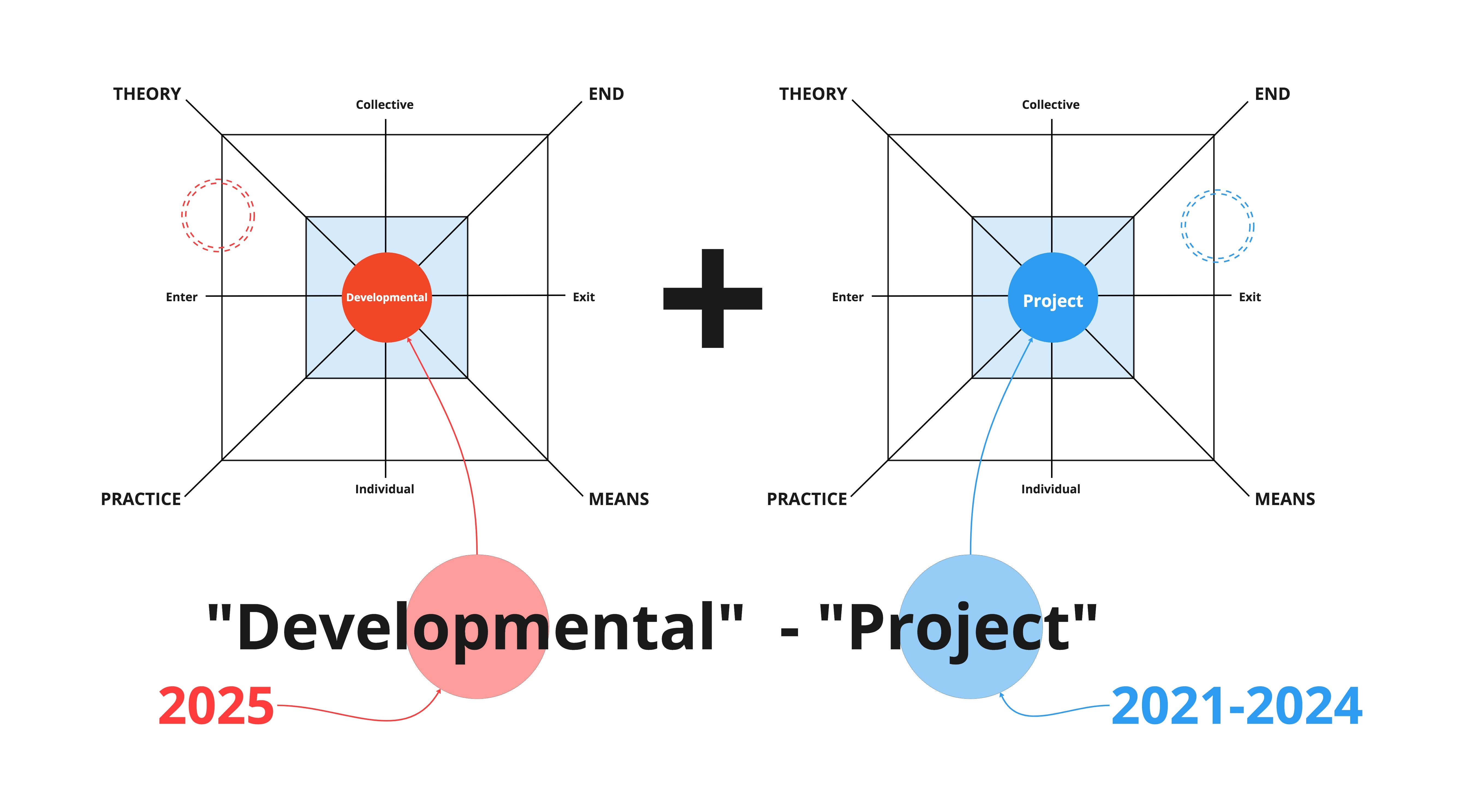

This reflection encouraged me to pay closer attention to the “Developmental” aspect of the “Developmental Project” concept. Eventually, I entered the Creative Swapping moment. See the diagram below.

Creative Swapping is defined as the dynamic structure in which the focus can switch between the two component words of a concept or theme. The mechanism is “Creative” because each switch produces a new theoretical perspective, resulting from the change in attention allocation between focus and background.

From 2021 to 2024, I used the “Developmental Project” concept to name the basic model of the Project Engagement Approach; however, the theoretical focus was on “Project,” while the “Development” concept remained in the background.

In 2025, the new book’s subtitle, The Project Engagement Approach to Adult Development, initiated a Creative Dialogue space between the approach and practice. In this new context, the Creative Swapping moment emerged.

During this moment, the “Development” concept became the new theoretical focus, while “Project” became the background.

Creative Swapping provided me with a new perspective to revisit all my past works on the Project Engagement Approach. I suddenly realized that some works previously treated as secondary now assumed primary significance, at least in the context of the new possible book.

In the following section, these ideas will be explored in detail.

Part 2: The Landscape

To better understand the structure and dynamics of the Developmental Project concept, I use an ecological metaphor. In this metaphor, the concept itself is seen as a living entity, with multiple interconnected elements that support both conceptual development and practical application. Each element of the metaphor represents a different dimension of the concept:

- Lotus Pond represents the field of adult development

- Lotus Flower symbolizes the organization of key themes within the concept.

- Lotus Leaf represents methods for developing creative identity.

- Lotus Seed illustrates the containers that carry and transmit both agency and the Mental Platform.

- Lotus Rhizome reflects the broader creative enterprise and its networked activities.

Through this ecological metaphor, the following sections explore how the Developmental Project concept unfolds across these dimensions, highlighting its evolving nature and practical significance.

2.1 Lotus Pond: Adult Development

In my 2021 book draft Platform for Development, I noted that the book examines the intersection between digital platforms and adult development. I have been engaged with these two domains for over ten years. As a participant in digital platforms, I am both a user, a curator and a maker. In the domain of adult development, I have founded several non-profit online communities aimed at supporting the life development of university students and young professionals.

Over the past several years, I also developed multiple models to guide my reflections on practical experiences with digital platforms and adult development. For example, I became interested in biographical studies after writing my first learning autobiography in 2015. In 2016, to help a friend, I developed a framework called Career Landscape, inspired by Activity Theory, Communities of Practice, and other theoretical resources. Later, in November 2020, I reconstructed this framework using additional theoretical foundations, resulting in a new method named the Life-as-Activity approach (v0.3).

From 2021 to 2025, I continued working on several projects related to adult development, though these projects belonged to different theoretical enterprises. Collectively, they produced a series of knowledge frameworks and book drafts; six of these drafts are listed below.

Although these projects and drafts did not use the “Development” concept as their primary focus, they concentrated on individual life development (rather than organizational development) and addressed significant aspects of adult development one by one, such as Discovery, Curation, Strategy, Narrative, and so on.

2.2 Lotus Flower: Six Themes

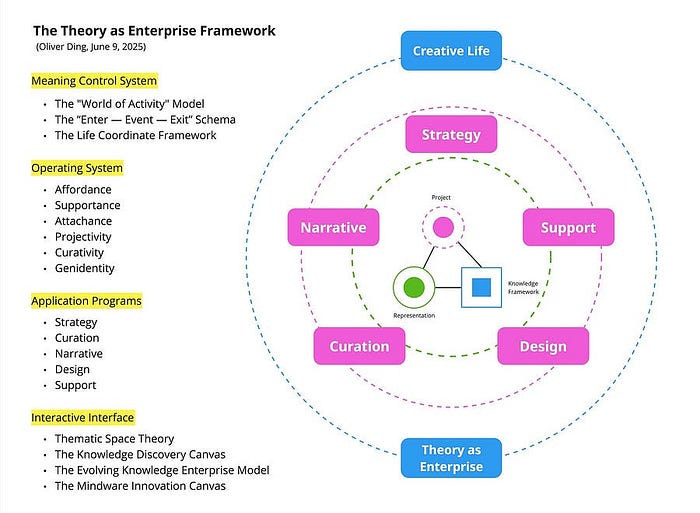

In June 2025, I identified five key functions within the “Theory as Enterprise” Framework (see the diagram below).

- Stratgegy

- Curation

- Narrative

- Design

- Support

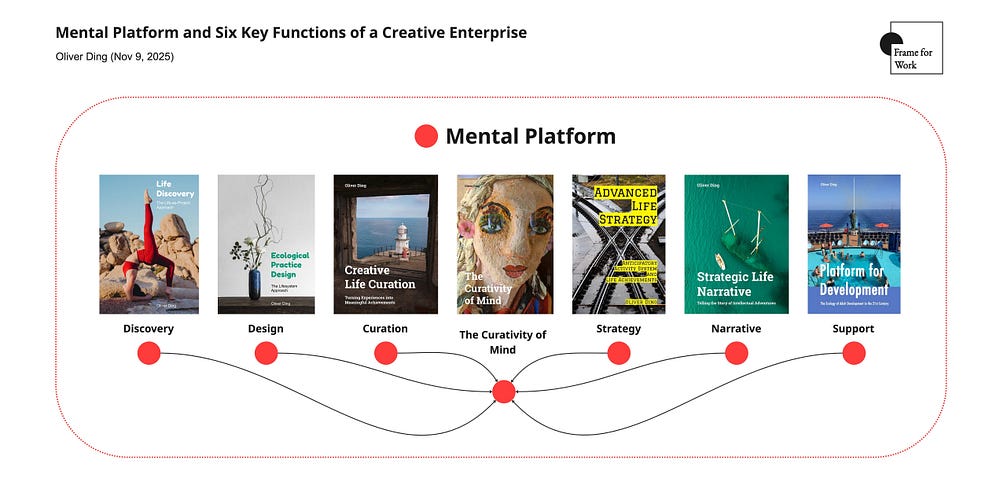

On November 9, 2025, I added “Discovery” as a sixth key function and linked all six functions to the concept of Mental Platform and the broader theme of Curativity of Mind (See the diagram below).

In the Cultural Projection Model (2025), I proposed that the concept of “Enterprise” refers to a series of Projects, while “Mental Platform” refers to a concept system — one that functions as a Concept System as a Means to support the development of an Enterprise.

If we continue to curate these themes together under the umbrella of “Developmental Projects,” the resulting structure resembles a flower.

As the creator of the “Developmental Project” concept, I worked on a series of projects and developed a “Mental Platform” — a concept system — that could support six key functions of a Creative Enterprise or a series of Developmental Projects. Each theme corresponds to a book draft that represents relevant knowledge frameworks, methods, and case studies.

The ecological metaphor provides the unifying structure — the flower itself — within which the six functions operate as integrated, mutually supporting capabilities. In this way, the six themes become sub-themes of the evolving “Developmental Project” concept system.

For others who use the “Developmental Project” concept to support their developmental projects, this concept system — an integrated system for adult development — offers rich resources across the six key functions. Part 3 demonstrates three of these functions in practice, showing how they operate across spatial, temporal, and integrative dimensions.

2.3 Lotus Leaf: A Way to Shape Creative Identity

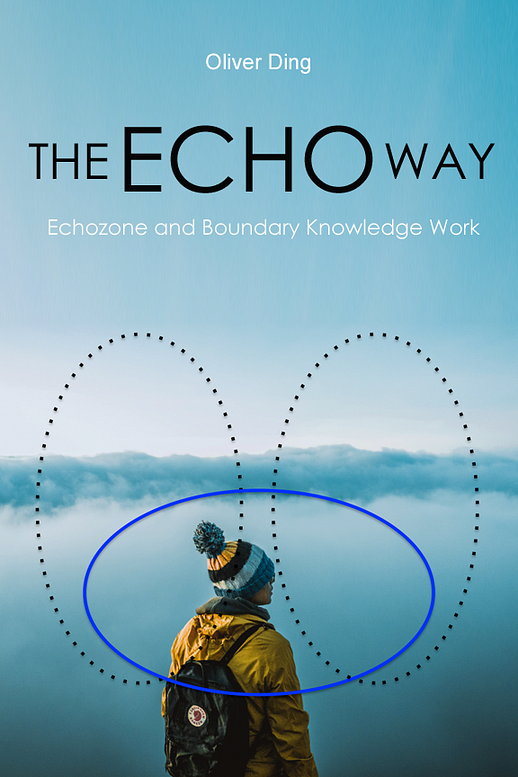

The concept of “Identity” is a key part of the Developmental Project Model. Over the past few years, I developed several knowledge models to address the complexity of identity development. In this process, the identity of the “Developmental Project” concept itself also evolved. A significant example of this transformation is the emergence of The ECHO Way between 2020 and 2021, in which the Developmental Project concept is operationalized as the “Project I” model, distinct from the Developmental Project Model.

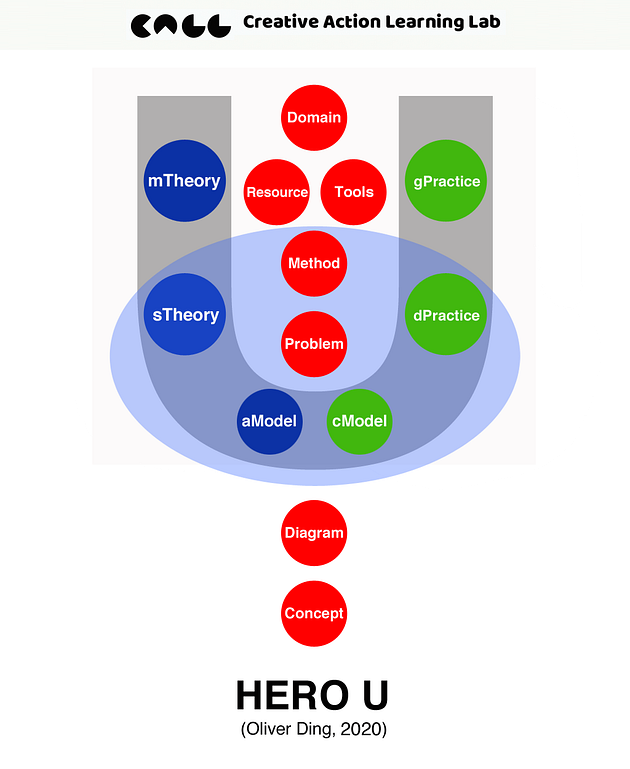

In April 2021, I joined an online program and shared my reflections on the HERO U framework and related works. This reflection process led to the creation of a new book draft titled THE ECHO WAY, written in Chinese, spanning 312 pages. Its subtitle is Echozone and Boundary Knowledge Work, and it documents my reflections on connecting Theory and Practice. I chose to write in Chinese to share these ideas with friends who were participants in the program.

Prior to 2021, I had mainly applied the HERO U framework to knowledge curation and the Theory-Practice connection. In 2021, I expanded the use of the diagrams within the HERO U framework to other areas, such as platform innovation and personal innovation. On March 24, 2021, I published Platform Innovation as Concept-fit. On May 25, 2021, I published Personal Innovation as Career-fit. On June 4, 2021, I created a new diagram titled Global-fit for Cross-Cultural Innovation, after an insightful conversation with a friend who is the founder of a cross-cultural innovation project.

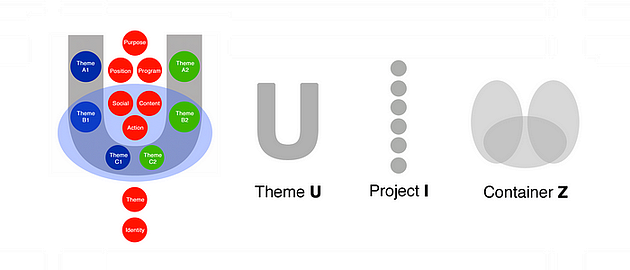

By June 2021, I recognized the need to reframe HERO U under a new name to reflect its expanded focus on boundary innovation. The resulting framework, The ECHO Way (v2.0), is a practical system guiding research, design, and development. It integrates diagrams, concepts, and methods, using Diagram Blending to curate multiple diagrams into a unified framework. The three primary diagrams in this process are:

- Theme U

- Project I

- Container Z

In the ECHO Way, the “personal conditions” dimension was redefined as “Project I,” linking to the Developmental Project Model. Eight elements of the Developmental Project Model were displayed in an “I” shape to fit the visual structure of the ECHO Way.

The Developmental Project Model highlights the following elements:

- Theme

- Identity

- Purpose

- Program

- Position

- Social

- Action

- Content

As the basic model of the Project Engagement Approach, the Developmental Project Model provides a general framework for understanding projects, while the Project I model allows for situational customization for domain-specific applications; both models are useful within the “Developmental Projects” concept. For example, the HERO U framework applies the following elements in its “Project I” component:

- Domain

- Resource

- Tools

- Method

- Problem

- Diagram

- Concept

I also guided a friend to develop a new “Project I” model for the field of architecture. More details are available in The ECHO Way (v2.0) and HERO U — A New Framework for Knowledge Heroes.

In February 2022, I applied the ECHO Way (V2.0) to the Life Discovery Project and defined three phases of the process:

- Life U: Think with the Theme U diagram.

- Project I: Act with the Developmental Project model.

- Echo Z: Reach the end of the journey: an expected place.

This three-phase structure emphasizes “Think — Act — Reach” actions. The second type of action is designed with the Project I diagram.

By connecting Theme U, Project I, and Echo Z together, we see a large context of Developmental Projects. In this way, the ECHO Way provides a way to shape creative identity by integrating thinking, doing, and sense-making.

Building on this foundation, I further developed the Thematic Identity Curation Framework, a toolkit to support creative identity development, in which Developmental Projects remains a central component.

2.4 Lotus Seed: Container Z

A key process of adult development is self-transformation. While working on a series of Developmental Projects, Container Z, the third component of The ECHO Way, provides a concrete approach to transformation by engaging with opposite themes.

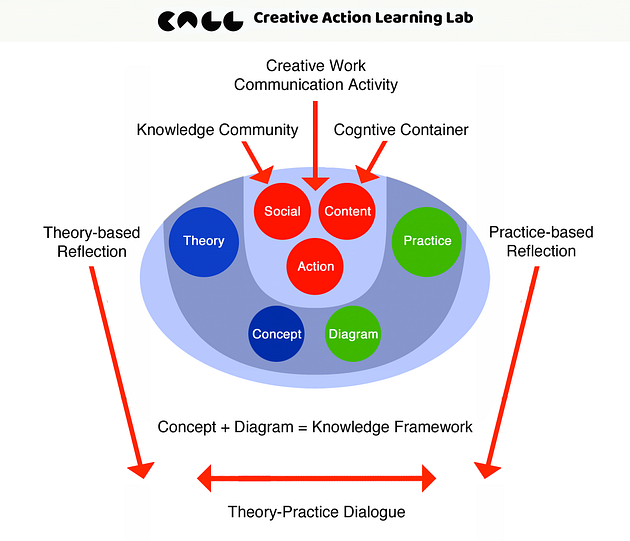

For example, in the Echozone of the Activity U project, the diagram below illustrates how career themes and developmental projects interact.

It highlights two pairs of opposite themes. The “Theory vs. Practice” fit is explored through three movements:

- Practice-based Reflection: building preliminary models using intuition.

- Theory-based Reflection: refining these models with theoretical resources.

- Theory-Practice Dialogue: transforming models into frameworks and testing them through case studies.

A practical example of these three steps is presented in the article Platform Innovation as Concept-fit.

Sharing complex personal knowledge within the Echozone is challenging. To address this, I designed visual diagrams and wrote a book documenting the process. The second part of THE ECHO WAY dedicates 76 pages to describe my experiences with the Echozone, covering deep thinking, personal reflection, and boundary dialogue.

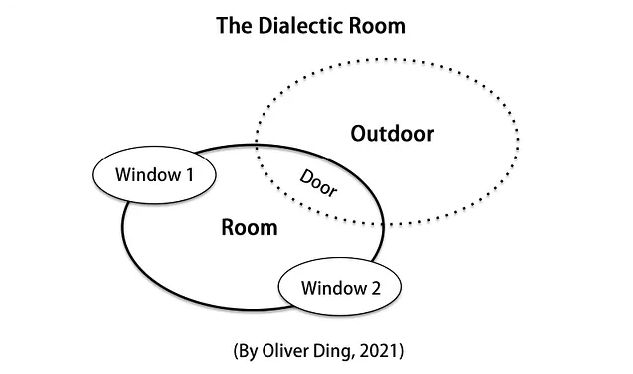

In 2021, I developed the Dialectic Room, a meta-diagram designed to apply dialectical logic to manage structural tensions. Its origin lies in the “germ-cell” diagram of Project-oriented Activity Theory.

We can consider a tough situation with structural tension as a room with two windows and one door.

- a tough situation = a room

- a structural tension = a pair of Opposite Themes = two windows

- a final action = a door

A room is a container that separates the inside space from the outside space. There are several kinds of actions people can perform within a room. Here, I focus on a particular type of action: connecting the inside space to the outside space. Let’s call this action “Process.”

The two windows serve as interfaces that represent two “Tendencies.” Window 1 refers to Tendency 1, while Window 2 refers to Tendency 2. Each window provides its own view of the outside space.

Finally, there is a door that allows people to actually leave the room. The door refers to “Orientation,” which represents the direction of a real action — an act of moving from the inside space to the outside space.

Once you step into the outside space, you can treat it as a new room and repeat the same diagram.

The Dialectic Room, together with Hegel’s theory of concept, was often applied in conjunction with the Container Z component. It exemplifies the influence of Blunden on my practical work with the Developmental Projects concept, showing how structural tensions can be navigated and transformed into actionable insights.

More details, see The Dialectic Room: A Meta-diagram for Innovation and The Dialectic Room: Theoretical Foundations.

2.5 Lotus Rhizome: Creative Enterprise

As discussed above, a Creative Enterprise consists of a series of interconnected projects. By linking the concept of “Enterprise” with the “Developmental Project” concept, we can trace the deeper relationships among various developmental projects and understand how individual projects collectively contribute to broader developmental goals.

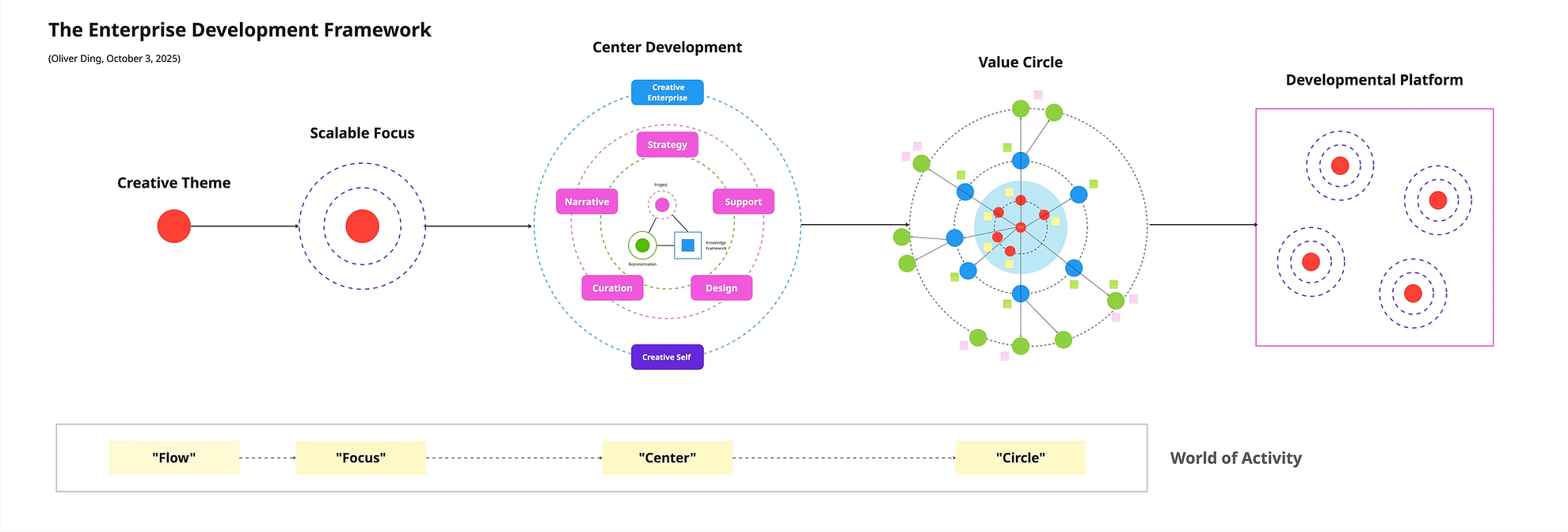

In October 2025, I developed the Enterprise Development Framework as part of the World of Activity Approach. This framework provides structured guidance for managing and evolving a Creative Enterprise, integrating insights from multiple projects, and supporting the coordination of both thematic and identity-related aspects of development.

The diagram above illustrates the complete journey of enterprise development, highlighting five stages of an evolving enterprise.

- Creative Theme

- Scalable Focus

- Center Development

- Value Circle

- Developmental Platform

The “Developmental Project” concept is relevant at all five stages, guiding both project-level and enterprise-level development.

- Creative Theme: the pre-Project stage.

- Scalable Focus: joining or initiating a project with a scalable object.

- Center Development: developing a series of projects, turning the scalable object into a creative center

- Value Circle: connecting the center to other related centers, forming a network of projects

- Developmental Platform: the scaled center becomes a platform, supporting more projects to emerge

This model can be applied to diverse social environments:

- Family: a series of developmental projects around the “Love — Legacy” thematic schema

- School: a series of developmental projects around the “Teach — Learn” thematic schema

- Organization: a series of developmental projects around the “Collaboration — Achievement” thematic schema

- Community: a series of developmental projects around the “Connection — Exploration” theme

- Market: a series of developmental projects around the “ Search — Change” theme

- Technological Platform: a series of developmental projects around the “Affordance — Supportance” thematic schema

- City: a series of developmental projects around the “Local — Global” thematic schema

- Theory: a series of developmental projects around the “Theme — Concept” thematic schema

From the perspective of the Project Engagement approach, all these types of social environments can be seen as the outcome of a special type of enterprise: a series of development projects structured around distinctive double-theme schemas.

Further discussion is provided in 4.5, Social Group as Product of Projects.

Part 3: Grasping the Concept

The phrase “Grasping the Concept” was inspired by Blunden, whom I mentioned earlier; he is also the author of Concepts: A Critical Approach. In November 2020, we had a short thematic conversation about concepts via Gmail. He used the expression “… grasped with two different concepts…” to describe two different views of Activity Theory.

At that moment, I realized that “grasping the concept” lies at the heart of concept-related practice. Three years later, in November 2023, I used this phrase to title a book draft: Grasping the Concept: The Territory of Concepts and Concept Dynamics.

In this part, I share several stories that reveal how we can grasp the “Developmental Project” concept in practice. Following the six themes introduced in Part 2, I selected three projects that illustrate three key dimensions: Life Discovery (spatial), GAP Projects (temporal), and Mapping Strategic Moves (integrative). Together, they show how the developmental process operates across space, unfolds through time, and weaves both into meaningful trajectories.

These three examples demonstrate how the “Developmental Project” concept works in practice — showing how it unfolds through concrete projects, each highlighting a key theme. The full elaboration of all six functions will be presented in the main body of the book.

3.1 The “Life Discovery” Project (spatial)

The Developmental Project Model focuses on the “Project” level. At the higher level of multiple projects, we can use different models — such as Chain, Network, or System — to explain the complexity.

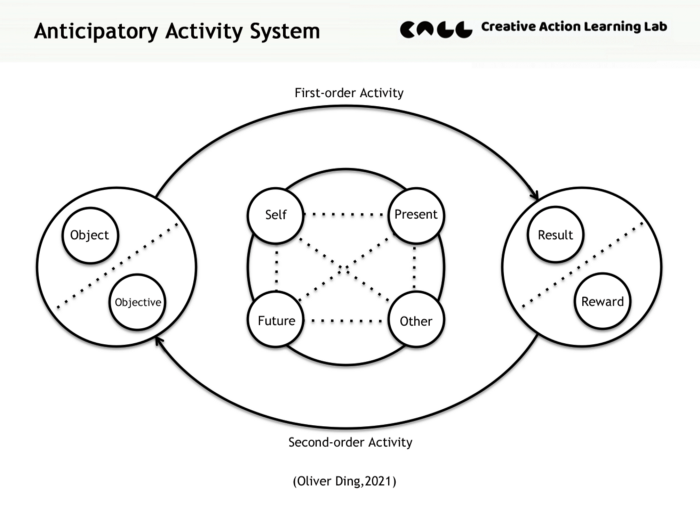

In August 2021, I developed the Anticipatory Activity System (AAS) Framework, inspired by Activity Theory, Anticipatory System theory, Relevance theory, and other theoretical resources. The framework models a specific structure — “Self, Other, Present, Future” — at the “System” level.

An Anticipatory Activity System is composed of two parts: First-order Activity and Second-order Activity. While a First-order Activity begins with a clearly defined objective, that objective is itself the outcome of a Second-order Activity.

At a lower level, both First-order Activity and Second-order Activity can be understood as Projects. In this way, the AAS Framework integrates with the Project Engagement Approach as a hierarchical system.

From January to June 2022, I worked on the Life Discovery project and developed the Life-as-Project Approach. The “Life Discovery” project was treated as an example of a Second-order Activity.

During this six-month journey, several significant moments appeared:

- Life as Sailing (Jan 4, 2022)

- A Toolkit (Feb 7, 2022)

- A Canvas (Feb 27, 2022)

- A Program (Mar 22, 2022)

- Significant Insights (Apr 25, 2022)

- Hiddenness (May 5, 2022)

- Project Network (Jun 7, 2022)

I use Life Discovery Activity as a general term and Life Discovery Project to refer to particular projects. During these six months, I also joined three Life Discovery Projects:

- Shaper & Supporter Lab — researcher

- AAS Board — coach and service designer

- Slow Cognition Project (Phase I) — creator

To be honest, I did not define the term Life Discovery at the beginning. I simply used it as a name for a toolkit, a canvas, a framework concept, and a program. I grasped the “Life Discovery” concept through these real-life activities because they all centered on discovering what a person should do in the next stage of life.

This journey was significant in developing the Anticipatory Activity System (AAS) Framework because the “Second-order Activity” concept was a brand-new concept within the field of Activity Theory. In contrast, “First-order Activity” refers to traditional activities with predefined objectives. For life development, many projects belong to Life Performance Projects, which are First-order Activities.

The Life Discovery Project, the Life Performance Project, and the AAS Framework bring a spatial structure to the Project Engagement Approach. They also indicate a direction for further development of the “Developmental Project” concept.

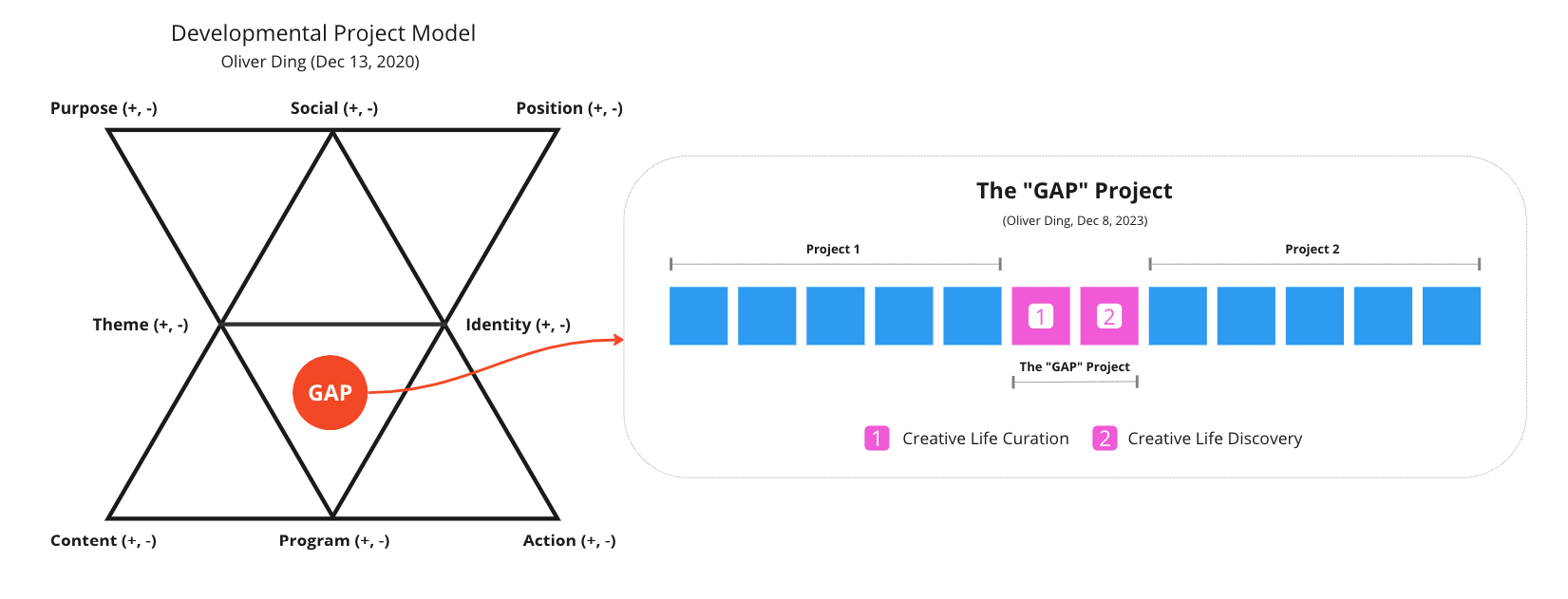

3.2 GAP Projects (temporal)

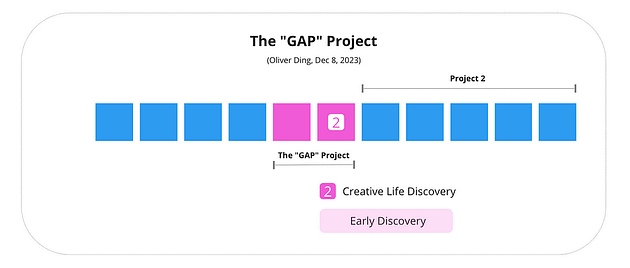

In 2022, I developed the concept of GAP Projects, inspired by the idea of a “gap year.” GAP Projects are informal activities that occur between formal projects and serve as structural opportunities to reflect, explore, and prepare for new work. They are classified into two types:

- Before Projects: exploratory activities without a predefined objective, such as Creative Life Discovery.

- After Projects: reflective or curative activities based on completed work, such as Creative Life Curation.

GAP Projects are a structural choice — to run a GAP project or not — between formal projects or life journeys. They help capture significant insights that may guide future activities or projects.

Creative Life Curation (After Project)

In 2022, I transformed my personal reflection habits into a structured knowledge framework, resulting in the book draft Creative Life Curation: Turning Experiences into Meaningful Achievements.

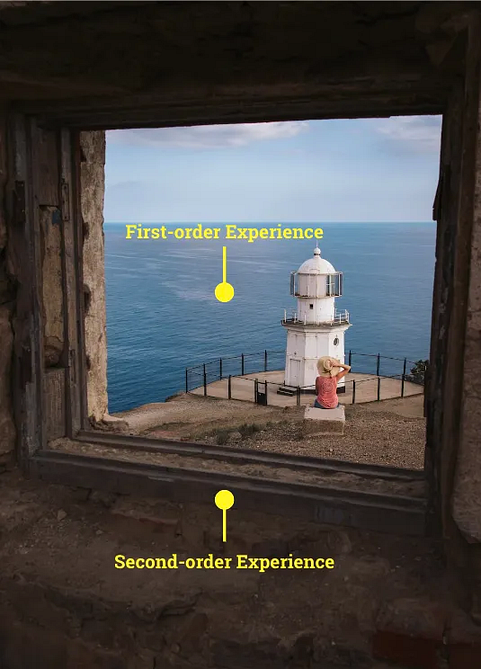

First-order Experience refers to normal life experiences — for example, the girl sees the ocean. Second-order Experience refers to Creative Life Curation, in which these normal experiences are curated into meaningful wholes.

I followed a consistent strategy for running these Creative Life Curation projects:

Project (Actions) → Stories (Notes) → Model → Creative Work

I relied on notes as raw materials to run the creative curation process. During a project, we could write notes about the project. After closing the project, these notes could be reused for a Creative Life Curation project.

The Creative Life Curation framework involves analyzing projects, with units of analysis such as Creative Projects. Examples include:

- How did I develop the “Product Engagement” Framework? — March 21, 2023 (three-week writing project)

- The ECHO Trip: A 10-day Road Trip and Creative Life Curation — July 27, 2023

- Engaging with Lui’s Theoretical Sociology — August 9, 2023 (a three-week project reflecting on a one-year informal learning and thematic conversation project)

These projects demonstrate how an After Project curates past experiences into meaningful outputs and prepares for the next phase.

Creative Life Discovery (Before Project)

Before Projects focus on exploration and discovery. They often lack clear objectives or raw materials, making them more challenging than After Projects.

In 2023, frameworks like Strategic Thematic Exploration and Thematic Space Theory (TST) guided my Creative Life Discovery projects. Three examples include:

- The Mental Moves Project (Started on March 24 and closed on July 31) — creating a detailed plan

- Projectivity as Cultural Attachance (Started on Oct 20 and closed on Oct 30) — embracing unexpected discoveries

- Discover Thematic Spaces of Creative Life and Thematic Space Theory (Started on Oct 31 and Closed on Dec 5) — navigating a messy set of ideas

These projects generate significant insights, which are outcomes that may indirectly or directly spark future projects. Insights often become visible only retrospectively, once they shape subsequent work.

Timing for Structural Choices

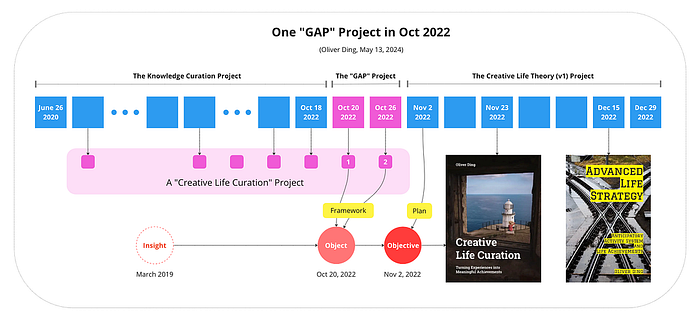

The timing of GAP Projects is deliberate, positioned between formal creative projects or long-term creative journeys. For example, in October 2022, I closed a three-year journey on the Knowledge Curation Project. At that time, I decided to run a GAP project to reflect on this journey, which resulted in the Creative Life Curation method and the Creative Life Theory (v1) project.

- Before: The Knowledge Curation Project (June 26, 2020 — Oct 18, 2022)

- After: The Creative Life Theory (v1) Project (Nov 2, 2022 — Dec 29, 2022)

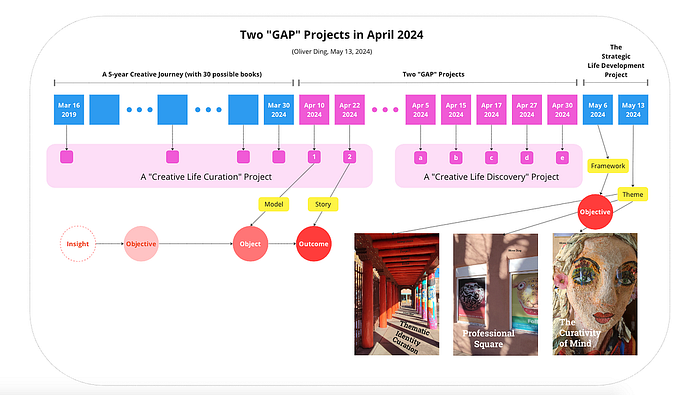

In March 2024, I noticed that I had written and edited 42 book drafts from March 2019 to March 2024. This timing inspired the discovery of a Thematic Analogy between October 2022 and March 2024. It further encouraged me to run a Creative Life Curation project in April 2024, reflecting on the five-year creative journey. The project was guided by an Anticipatory Analogy: I anticipated that the outcomes in April 2024 would echo those of October 2022, which informed my decision-making and creative direction.

This process ultimately led to a new project, Strategic Life Development, and a meta-framework for Theoretical Psychology.

Running a GAP project, or choosing not to run one, is a Structural Choice after closing a creative project or a long-term creative journey. For many people, this is a hidden choice.

More details can be found in A 5-year Creative Journey and Two “GAP” Projects.

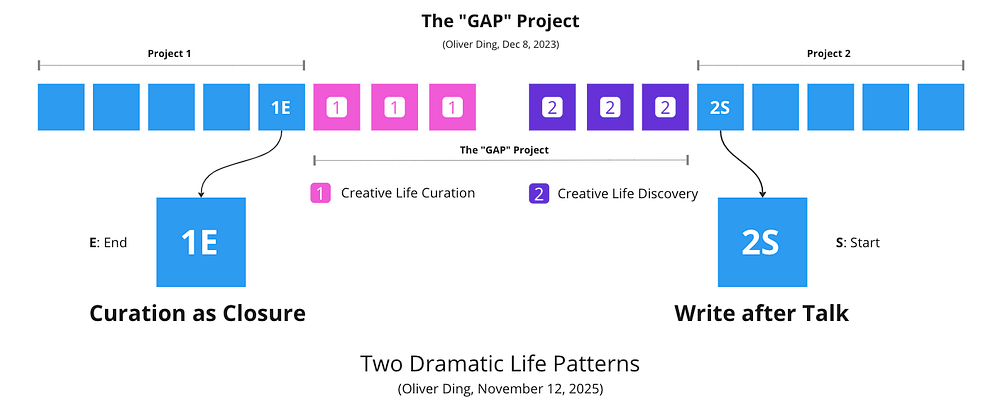

Recently, this exploration of the temporal aspects of Developmental Projects extended beyond GAP Projects, leading me to discover two new dramatic life patterns (see the diagram below):

- Curation as Closure (1E): I often curate a collection of articles to edit a book draft and formally close a project. This occurs before the end of Project 1.

- Write after Talk (2S): I often engage in discussions or conversations with friends after writing ideas or articles at the start of a new project. This occurs after the start of Project 2.

These patterns, together with the GAP Projects, highlight the temporal complexity of the “Developmental Project” concept and reveal how timing, reflection, and sequencing shape creative trajectories.

3.3 The “Mapping Strategic Moves” Project ( (integrative)

In May 2024, I developed version 3.1 of the Project Engagement approach. While version 1.0 focused on the Developmental Project Model, version 3.0 expanded on this by curating a range of knowledge frameworks to explore project-oriented social ecology.

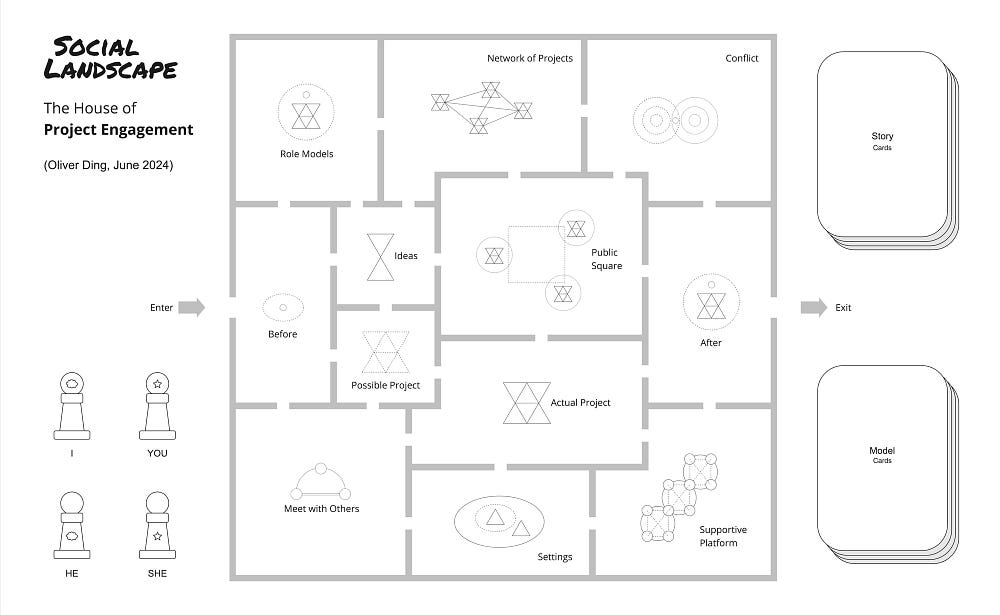

In June 2024, to support a friend’s workshop, I simplified the Project Engagement approach (v3.1) by selecting only its Map component. This led to the creation of the House of Project Engagement. See the diagram below.

Designed as a Map, the House of Project Engagement uses a “Museum” metaphor to represent space. The House is organized into 12 thematic rooms, with each room representing a distinct type of social landscape. Together, these rooms depict the following themes:

- Before

- Role Models

- Ideas

- Possible Project

- Meet with Others

- Actual Project

- Settings

- Supportive Platform

- Public Square

- Network of Project

- Conflict

- After

The methodology behind the design is framed by the “Map — Move — Model — Method — Meaning” schema.

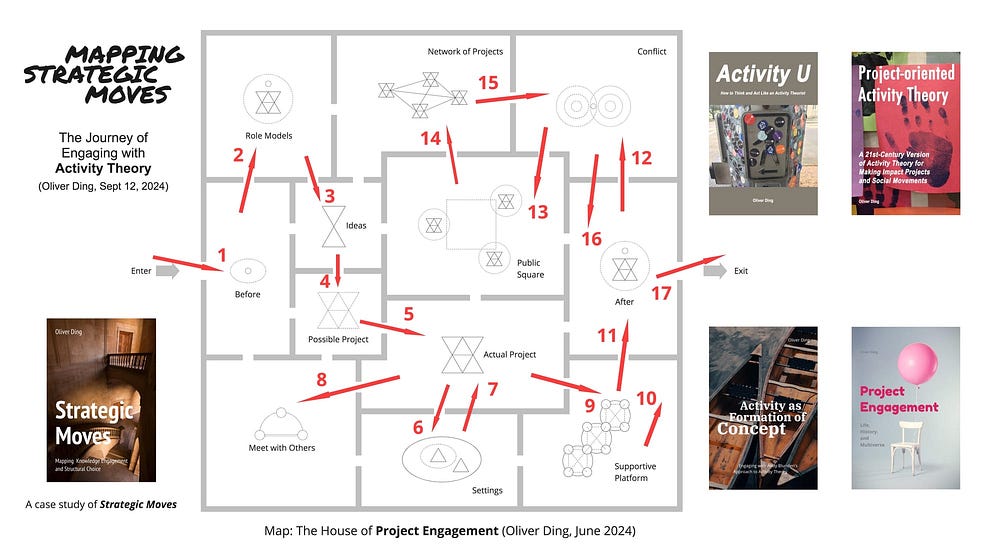

For example, the diagram below represents 17 Moves in my journey of engaging with Activity Theory.

The House of Project Engagement functions as a thematic Map, structured with 12 thematic rooms that represent a series of social landscapes.

Each thematic room can incorporate relevant knowledge frameworks as Models.

The approach of using these 12 rooms to map life courses and creative journeys serves as a distinctive Method. For instance, I developed the Mapping Strategic Moves method within the framework of the House of Project Engagement.

By integrating Maps, Moves, and Reflection, this methodology supports life narrative practices, facilitating the process of Meaning discovery.

As an integrative example of the Developmental Project concept, the Mapping Strategic Moves Project synthesizes spatial, temporal, and thematic dimensions. It shows how individual projects, temporal sequences, and social landscapes can be coordinated into a coherent framework, enabling reflection, learning, and strategic decision-making across multiple levels of activity.

Part 4: Reclaim the Vision

In Collaborative Projects: An Interdisciplinary Study (2014), Blunden wrote a long introduction titled “Collaborative Project” as a Concept for Interdisciplinary Human Science Research, highlighting several key ideas of his project-oriented approach to human activity.

Although I use the “Developmental Projects” concept as my core idea of the ecological approach to adult development, my approach echoes Andy Blunden’s vision to some degree.

In 2021, I introduced Blunden’s ideas in a book draft, Project-oriented Activity Theory. Now it’s time to revisit Blunden’s original vision.

4.1 Project as a Unit of Activity and Human Science

In the 2010 book An Interdisciplinary Theory of Activity, Blunden suggests that the “Project” concept be a unit of analysis for an interdisciplinary theory of activity. In the 2014 book, he reclaims the Project concept as an interdisciplinary concept in human science.

The human sciences are fragmented into myriad disciplines, but a veritable chasm separates those disciplines which study the individual person and their actions from those disciplines which study human beings en masse: economics, history, political science and so on. The lack of a concept which meets the needs of science on both sides of this chasm mirrors the condition of modern life: individuals dominated by great processes of societal life in which they play no part. Could Activity Theory with “project” as a unit of activity, provide a way to overcome this gap by using a shared conceptual language across both domains?

…

Writers have come to the notion of “project” as an important concept in their work by various paths, from reflections on Cultural-Historical Activity Theory, social work, psychotherapy, Marxism or the study of social movements. But “project” is also a concept which has become more and more prominent in the language of everyday life, whether talking about science and the arts, hobbies, political life or personal biographies. The combination of the philosophical sediment that the concept has acquired in the history of the human sciences, with the connotations that the word has accrued from everyday usage makes the concept of “project” a powerful tool for interdisciplinary science. This is the idea I proposed in my book An Interdisciplinary Theory of Activity (Blunden, 2010)

Source: Collaborative Projects: An Interdisciplinary Study (2014), p.1, p.8

In the past years, while developing the Project Engagement Approach, I also used it to guide my knowledge projects and theoretical enterprises. This theory-practice connection gave me a real opportunity to test Blunden’s ideas. In general, I accepted that while the “Activity” concept stays at the abstract level, the “Project” concept can work at the concrete level. For example, consider two terms about the Creative Life Curation method:

- the “Creative Life Curation” Activity

- a “Creative Life Curation” Project

The first term is used to describe all projects that use the Creative Life Curation method as a category, while the second one refers to a particular project that applied the method. So, using Project as a unit of activity creates a balance between the abstract theoretical concept of Activity and the daily uses and empirical research within Activity Theory.

My passion for theoretical development and knowledge engagement also echoes Blunden’s vision for developing a project-based interdisciplinary approach. To realize this vision, I adopted three strategies:

- Developing Curativity Theory to emphasize that “curation” is a general human practice, highlighting the ecological value of turning pieces into a meaningful whole.

- Focusing on connecting THEORY and PRACTICE by developing a series of tools such as models, diagrams, canvases, and corresponding methods.

- Taking knowledge creators’ life development — including creative cognition and life strategy — seriously in order to support scholars across all disciplines and professionals from all fields.

When unfolding these three strategies, the Project Engagement Approach and the tradition of Activity Theory offer me many useful ideas for running real knowledge projects. The “Creative Life Curation” activity and its related projects are good examples.

Ideas from Hegel’s theory of concept, highlighted by Blunden, also inspired the Dialectic Room meta-diagram and the ECHO Way framework.

In general, I pay attention to knowledge creators’ Developmental Projects and their Creative Enterprises, no matter which discipline or field they come from. In this way, I indirectly contribute to the development of all disciplines and fields by supporting creative people.

4.2 A Project is a concept of both Psychology and Sociology

In the long introduction, Blunden reviews methodological individualism and dichotomies in the social sciences.

The unit of analysis for many human sciences, especially those in the analytical tradition, is the individual person. And for the most reductive strands of psychology and medicine generally the individual is also the Gestalt…Alongside the concept of the individual is a system concept of the “social group,” the unit for the social sciences, generally conceived of as an aggregate of individuals sharing some attribute in common,…But for a growing body of human science, this analytical approach is unsatisfactory.

…

“Project” as a unit of Activity and as a starting point for Activity Theory is an interdisciplinary concept for the following reason. A project is the focus for an individual’s motivation, the indispensable vehicle for the exercise of their will and thus the key determinant of their psychology and the process which produces and reproduces the social fabric. Projects therefore give direct expression to the identity of the sciences of the mind and the social sciences. Projects belong to both: a project is a concept of both psychology and sociology. Social and political theory resting on the concept of “project” is humanist because it gives realistic expression to the agency of individuals in societal affairs and concrete content to social relations.

Source: Collaborative Projects: An Interdisciplinary Study (2014), p.13, p.15

In practical work, it is a challenge to build a theoretical approach that is both a psychology and a sociology. Blunden’s vision requires bridging this gap, which I addressed through two complementary strategies.

My strategy operated at two levels. At the operational level, I introduced the “Outside — Projecting — Inside” triad as a basic ecological form that expands the internalization–externalization principle to describe how people engage with social environments. In this context, a project functions as a primary type of social environment.

At the theoretical level, I worked on creative dialogues between Activity Theory and ecological psychology, adding the concept of “Social Environment” and the “Projectivity” concept to the Project Engagement Approach. I also worked on creative dialogues between Activity Theory and Phenomenological Sociology, especially Alfred Schutz’s approach to subjective experience.

In Project Engagement: Outside, Projecting, and Inside, I introduced the Cultural Projection Model with a series of concepts. See the diagram below.

An important concept is the “Enterprise” concept, which is defined as a series of projects from the subjective perspective. At the Part dimension, the Self–Project connection represents “Project Engagement,” where an individual participates in a specific project. At the Whole dimension, Activity refers to the aggregation of individual projects, while Enterprise encompasses a series of self-directed actions that extend beyond immediate projects.

By incorporating the concept of Enterprise, the Cultural Projection Model emphasizes the subjective dimension of social life: a long-term, self-determined trajectory of actions. This notion was inspired by Phenomenological Sociology’s focus on subjective experience, not by any specific concept from that tradition.

Yet Ecological Psychology is a minority within the field of psychology, and Phenomenological Sociology is also a minority within the field of sociology. However, connecting them is an effective way to bridge psychology and sociology.

Ecological Psychology, Phenomenological Sociology, and Activity Theory share a common methodological stance: all three reject analytical decomposition and instead emphasize situated, holistic, and process-centered accounts of human action.

4.3 Identity is a Collaborative Project

Blunden highlights the concept of Identity of a person in the “Project” approach.

The unit of a social group is an individual, but the unit of a project is an action, just as the unit of activity is an action. A project is constituted by the actions of different people at different times, whilst individuals participate in different projects. “Project” is not another name for a “group”. A project is an aggregate of actions, a unit of social life.

…

There are many theories of identity and some CHAT researchers locate the source of identity in the projects a person is committed to and the roles a person takes in pursuance of those projects. This leads us to a humanist conception of identity, which is contrast to structuralist theories of identity based on difference and likeness. A person’s identity is that central, concrete proejct (or narrative) which is realized and concretized through a person’s life, subsuming the diversity of projects to which a person commits themselves over their lifetime: furtherance of their family, a profession, national or community goals, and so on. So a person’s identity is not just formed by collaborative projects, it is a collaborative project. Projects create selves at the same time as they create social bonds.

Source: Collaborative Projects: An Interdisciplinary Study (2014), p.16

The Developmental Project Model, the basic model of the Project Engagement Approach, considers the “Identity” concept as a key concept. At the empirical research level, it refers to two perspectives:

- The “Self” Perspective

- The “Project” Perspective

Both the individual and the project have their own evolving identities. I further developed a series of models and terms.

In The Center Journey (2022–2025), I discussed identity development from the “Self” perspective and the “Project” perspective, based on the Life-as-Project approach.

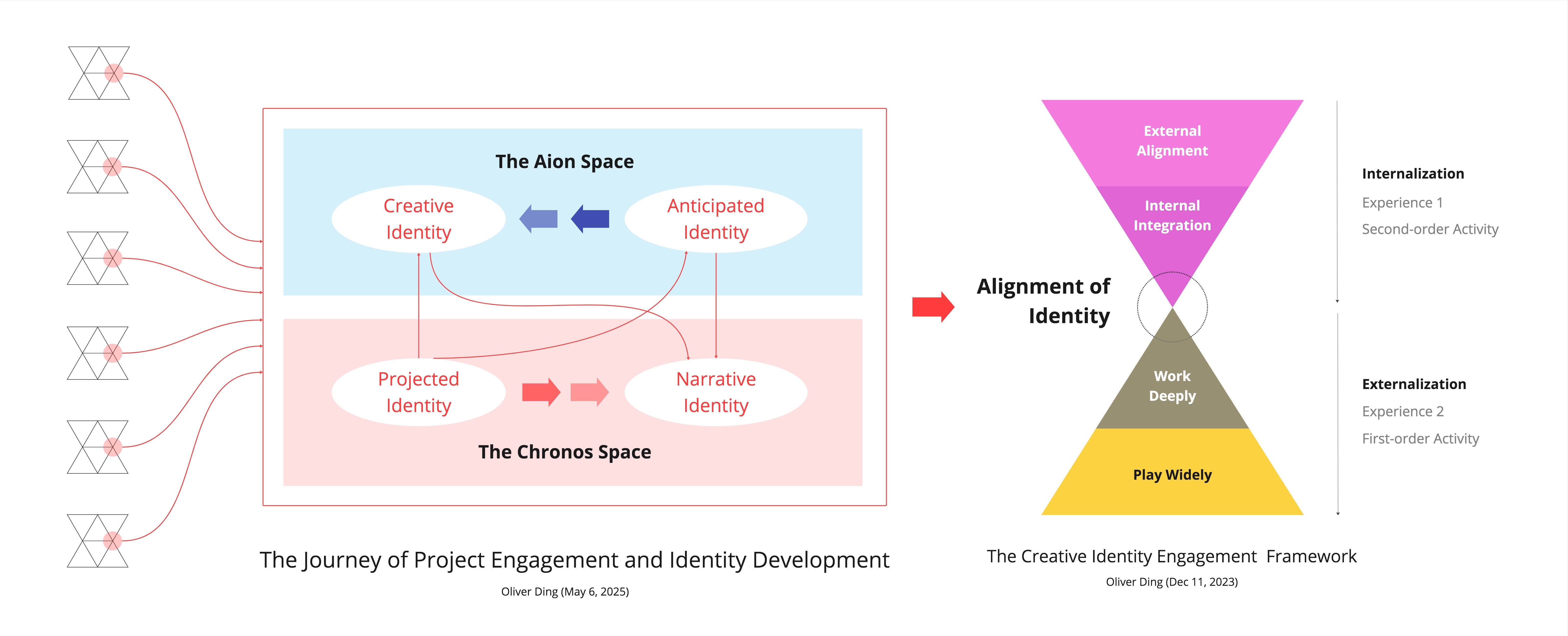

To deepen our understanding of identity development from the “Self” perspective, I propose four key types of identity: Projected Identity, Narrative Identity, Creative Identity, and Anticipated Identity. These four types of identity are placed in the Chronos and Aion spaces.

From the “Project” perspective, identity is not confined to an individual but instead extends to the project itself. To explore this further, I adopted the Creative Identity Engagement framework, which focuses on how a project’s identity is formed, evolved, and recognized in its field.

The diagram below represents the intersection of these two perspectives.

The diagram illustrates this integration across three dimensions:

- Left: a series of projects forming a broader journey

- Middle: four types of identity from the ‘self’ perspective

- Right: the project’s own identity development

Together, these two components form a Space Curation model, highlighting the dynamic evolution of both individual and project identities within the larger context of an evolving creative enterprise.

This approach connects the humanist approach and the structuralist approach by introducing time curation and space curation. In this way, identity development can be understood as a “meta-curation” project.

More details can be found in The “Aion-Chronos-Kairos” Schema.

4.4 Project as Formation of Concepts

One of Blunden’s most distinctive contributions is the claim that projects should be understood as processes of concept formation. Drawing on Hegel’s theory of concepts, Blunden argues that collaborative projects are not merely goal-directed activities but formative processes through which concepts develop, gain concrete content, and become shared means of understanding and action.

In August 2020, I read Andy Blunden’s 2012 book Concepts: A Critical Approach, which presents a “Hegel-Marx-Vygotsky” account of “Concept.” I realized that this provides an essential theoretical resource for supporting my idea of “Themes of Practice.”

According to Blunden, “Dualism has been around for a long time, and not only in the form of mind/matter dualism. One of the most persistent and debilitating forms of dualism today is the dualism of the individual and society, supported by sciences devoted exclusively to one or the other domain. Since concepts are units both of cultural formations and individuals minds, a theory of concepts confronts this head on…The development of the human sciences along two parallel paths, one concerned with human consciousness, the other concerned with social and political phenomena, can only serve to place barriers in front of people’s efforts to intervene in the affairs determining their own life. By understanding concepts as units of both consciousness and the social formation, I aim to create a counter to this disempowering dogma.” (2012, p.9)

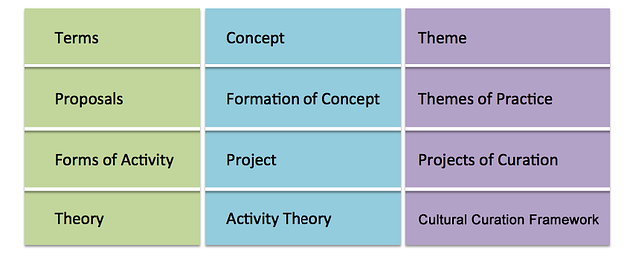

Since a Theme is a particular concept, I adopt Blunden’s proposal — the “Hegel–Marx–Vygotsky” account of Concept — as a theoretical foundation for the concept of “Themes of Practice.” Furthermore, I use Project-oriented Activity Theory to upgrade the General Curation Framework into a Cultural Curation Framework.

This theoretical connection enabled practical applications. From the perspective of Project-oriented Activity Theory, each curation program can be considered as a Project. Each “Theme of Practice” of a curation program can be considered as a Concept of a Project. Thus, the whole process of a curation program can be understood as “Initialization,” “Objectification,” and “Institutionalization” of a “Theme of Practice.”

In 2021, I introduced Andy Blunden’s notion of “Activity as Formation of Concept” in a book draft titled Project-oriented Activity Theory. Later, I used the notion of “Activity as Formation of Concept” to develop several knowledge frameworks. For example, I developed the Platform Innovation as Concept-fit framework and introduced it in the book Platform for Development in 2021.

To further connect my own idea of “Themes of Practice” and his notion of “Formation of Concept.” I consider a Theme as a special type of Concept — one that is actively emerging through practice rather than being already established in theory.

This distinction is crucial in the Project Engagement Approach:

- Concept: Relatively stable, theoretically articulated, shared in a community

- Theme: Dynamic, practice-embedded, personally or locally significant

A Theme can become a Concept through the formative process of developmental projects.

The transformation from Theme to Concept is not a simple linear process but involves several interrelated movements. For example, in January 2022, I worked on the “Life Discovery” project without a pre-defined concept of Life Discovery. Instead, the “Life Discovery” theme emerged from several real projects I worked on.

More details can be found in Activity as Formation of Concept: Engaging with Andy Blunden’s Approach to Activity Theory (book, v1, 2024).

4.5 Social Group as Product of Projects

Blenden also claims that “a social group as the product of a project” in the introduction.

Generally speaking, for the dominant currents of social theory, the unit of a social formation is taken to be a social group, and the unit of the social group an individual... Some theories, such as that of Bourdieu (1979), see social groups as actively constructed by their members, rather than as abstract general categories, but even in such cases the individuals remain trapped in a social structure whose dynamics lie beyond their horizon of action. But Activity Theory sees a social group as but the product of a project, as the appearance of a project at one stage in its development.

Source: Collaborative Projects: An Interdisciplinary Study (2014), p.17

In Vygotsky’s “Ecological Mind” and a New Approach to Adult Development, I proposed an ecological approach to human development by using the concept of Social Environment and Self.

In this model, a Social Group functions as the social environment for adult development. Moreover, following Blunden’s argument, these social environments emerge as the outcomes of development projects.

Here, I list several developmental projects that further develop Blunden’s notion:

- Family: a series of developmental projects around the “Love — Legacy” thematic schema

- School: a series of developmental projects around the “Teach — Learn” thematic schema

- Organization: a series of developmental projects around the “Collaboration — Achievement” thematic schema

- Community: a series of developmental projects around the “Connection — Exploration” thematic schema

- Market: a series of developmental projects around the “ Search — Change” thematic schema

- Technological Platform: a series of developmental projects around the “Affordance — Supportance” thematic schema

- City: a series of developmental projects around the “Local — Global” thematic schema

- Theory: a series of developmental projects around the “Theme — Concept” thematic schema

From the perspective of the Project Engagement approach, these eight types of social environments reveal a general pattern: every social formation can be understood as the outcome of a series of developmental projects organized around a distinctive double-theme schema. The specific relationship between the two themes in each schema — whether complementary, generative, or dynamic — remains open for further investigation.

This approach to differentiating social environments through their core thematic patterns echoes, in some ways, Niklas Luhmann’s method of distinguishing social systems through binary codes. However, whereas Luhmann’s codes operate at the level of communication systems (payment/non-payment for economy, legal/illegal for law), the double-theme schema operates at the level of developmental projects and human agency. This difference reflects a shift from systems theory to a project-oriented ecology: social environments are distinguished not merely by how they process information, but by what kinds of developmental projects they enable and organize.

This insight opens new directions for studying social development: not as abstract structural change or functional differentiation, but as the emergent product of developmental projects, reflecting the accumulated patterns of human action and thematic engagement within their environments.

Version 1.0 - November 29, 2025 - 9,095 words