The Concept of Narrative Identity

This article introduces the theory of self and identity by narrative psychologist Dan P. McAdams.

by Oliver Ding

Dan P. McAdams is a personality psychologist who prefers to use narrative psychology to explore the meaning of life and their impact on personality and life development.

In 1993, he published a book titled The Stories We Live By: Personal Myths and the Making of the Self and introduced a new theory of identity and self. The origins of the book’s core ideas can be traced to the first chapter of his 1985 professional book Power, Intimacy, and the Life Story.

Dan P. McAdams on Personality Psychology

McAdams is the author of The Person: An Introduction to the Science of Personality Psychology, a textbook. The first paragraph of the Preface of the book gives me a completely different view of personality.

Personality Psychology is not what it used to be. In the beginning, Freudians fought with Jungians, behaviorists lashed out against humanists, and everybody picked their favorite grand theory of personality and defended it to the death. Once upon a time, personality research was viewed to be trivial — mainly about dubious labels that we apply to people in order to predict what they will do, labels that turn out not to predict very well at all. But things have changed, and dramatically so. In the last twenty years, personality psychology has emerged as a vital and fascinating field of study, filled with new theoretical insights and important findings that speak to what it means to be a person in today’s world. With strong connections to social psychology, clinical psychology, life-span developmental studies, and cognitive neuroscience, personality psychology is today, first and foremost, the scientific study of the person. There is noting more interesting to persons than persons. And there is nothing more important. (2006, p.xvii)

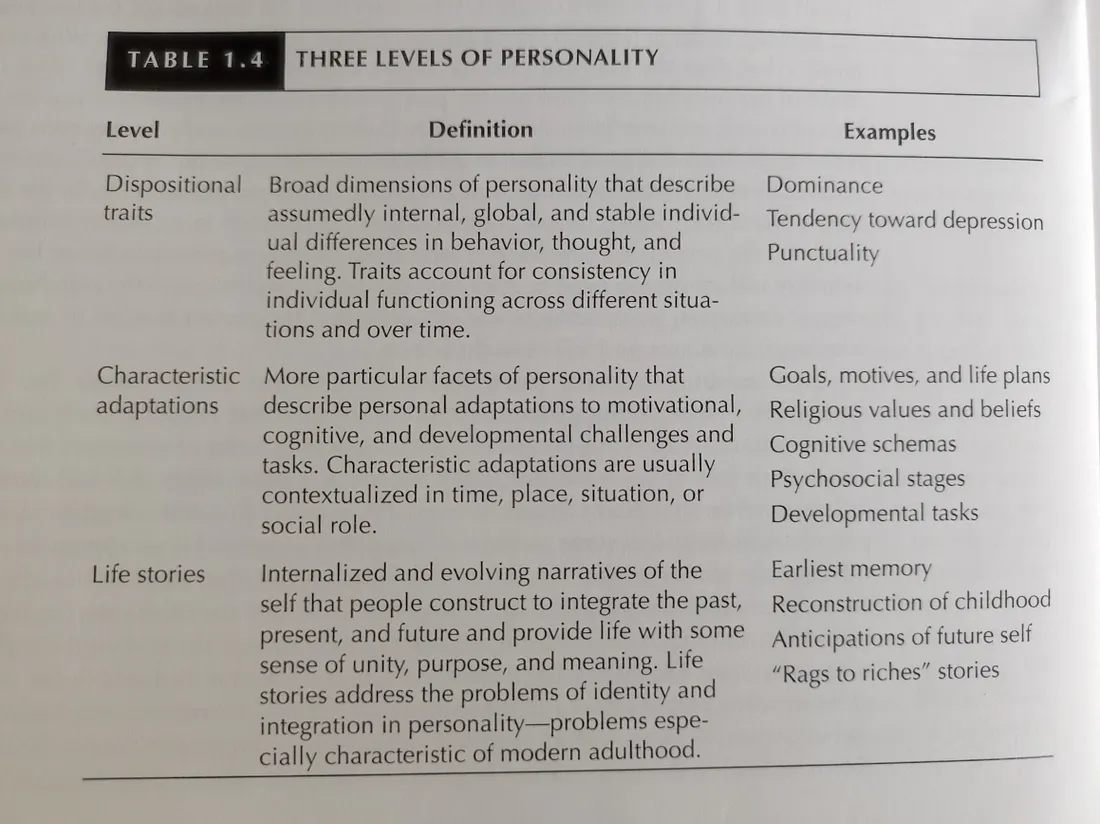

McAdams has a unique theoretical approach to understanding personality. He defines personality as a patterning of dispositional traits, characteristic adaptations, and integrative life stories set in a culture shaped by human nature. He uses this approach to connect classical theories with the latest research and insights.

The framework is also used to edit the book titled The Person: An Introduction to the Science of Personality Psychology. Here are the titles of the four parts of the book:

- Part 1: The Background: Persons, Human Nature, and Culture

- Part II: Sketching the Outline: Dispositional Traits and the Prediction of Behavior

- Part III: Filling in the Details: Characteristic Adaptations to Life Tasks

- Part IV: Making a Life: The Stories We Live By

The three-level personality model is described in detail in the following chart.

According to McAdams, this unique framework has an advantage in writing a textbook about personality.

Today’s undergraduate textbooks in personality psychology follow two different formats, both of which were developed in the 1960s. One type of book devotes a chapter apiece to each of the grand theories of personality developed in the first half of the twentieth century… The second type of text focuses on research topics and issues. While these books try to reflect the scientific work that personality psychologists actually do, they offer no vision or organization regarding what that work is fundamentally about…(2006, p.xvii)

What about the great theories? What about Freud? The behaviorists? They are still here, but I have reorganized theories and research to fit the integrated vision I have sketched above. This actually turns out to be very easy to do, for different theories address different aspects of human nature, cultural context, and human individuality. (2006, p.xviii)

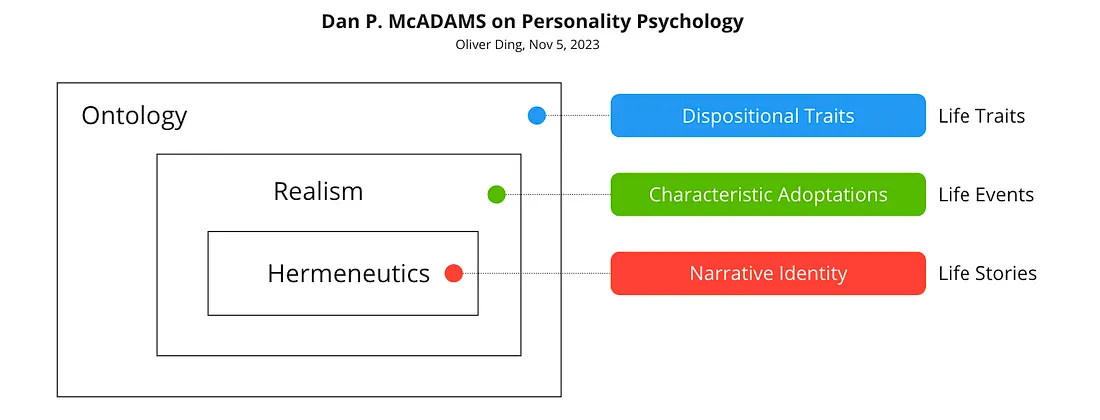

If we use the “Ontology > Realism > Hermeneutics” schema to examine McAdams’s model, we can see a unique theoretical framework of personality.

The new framework is more useful than traditional theories of personality because it creates a good balance between what is changeable and what is unchangeable. While dispositional traits are hard to change, narrative identity could be changed.

According to McAdams, the concept of personality is useful because we are interested in a significant question: What do we know when we know a person? He believed that his model was a good answer to the question:

In order to “know” a person — both from the standpoint of science and the standpoint of everyday life — we must first have some sense of what all persons have in common by virtue of human nature and how social context and culture shape every person’s life. Once we have an understanding of human nature and cultural context, then we can proceed to consider human individuality on three successive levels. (2006, p.xvii)

Level 3 is the level of the life story: What does a person's life mean? What gives a person's life a sense of unity and purpose?

Life Stories: Personal Myth and Narrative Identity

McAdams’s theory of self and identity was built around “the idea that each of us comes to know who he or she is by creating a heroic story of the self.” He used the term “Personal Myth” to describe this idea. (1993, p.11)

What is a personal myth? First and foremost, it is a special kind of story that each of us naturally constructs to bring together the different parts of ourselves and our lives into a purposeful and convincing whole. Like all stories, the personal myth has a beginning, middle, and end, defined according to the development of plot and character. We attempt, with our story, to make a compelling aesthetic statement. A personal myth is an act of imagination that is a patterned integration of our remembered past, perceived present, and anticipated future. As both author and reader, we come to appreciate our own myth for its beauty and its psychosocial truth. (1993, p.12)

What’s the difference between McAdams’s Personal Myth and my ideas of Story 1 and Story 2?

In 2022, I defined two types of stories for the “Flow — Story — Model” schema.

- Story 1: It is framed by Cultural Significance.

- Story 2: It refers to the Actual Narrative.

Story 1 emphasizes the Relevance aspect of the Story layer, while Story 2 emphasizes the Architecture aspect of the Story layer.

Story 2 refers to the real story which has not been told yet. A Story 2 is a set of immediate actions (experience) with a structure. The structure could be a planned project, a real project, and an imagined project.

Story 1 refers to telling stories that are framed by Cultural Significance. Once a person starts to share their stories with others, they must consider Relevance in the communicative context.

We can claim that McAdams’ Personal Myth is Story 3, and it connects to Narrative Identity.

- Story 1: It is framed by Cultural Significance.

- Story 2: It refers to the Actual Narrative.

- Story 3: It connects to Narrative Identity.

Story 2 is real but has not yet been told. Story 1 is real and has also been shared with others. Both Story 1 and Story 2 refer to our remembered past.

Story 3 is not entirely real because it comes from “an act of imagination that is a patterned integration of our remembered past, perceived present, and anticipated future.”

Since Story 3 also includes our anticipated future, it resembles a large ongoing life project, comprising both completed sub-projects and planned projects.

An important aspect of McAdams’s Personal Myth is not merely telling our life stories, but making ourselves through myth.

I do not believe that there are gods and goddesses within you, waiting to be recognized. We do not discover ourselves in myth; we make ourselves through myth. Truth is constructed in the midset of our loving and hating; our tasting, smelling, and feeling; our daily appointments and weekend lovemaking; in the conversations we have with those to whom we are closest; and with the stranger we meet on the bus. Stories from antiquity provide some raw materials for personal mythmaking, but not necessarily more than the television sitcoms we watch in prime time. Our sources are wildly varied, and our possibilities, vast. (1993, p.12)

Personal mythmaking looks like planning a life project with personal anticipation and cultural projection.

So far, we have found some similarities between McAdams’s Personal Myth and my Life-as-Project approach. However, there is a major difference between these two approaches.

According to McAdams, life stories are subjective meaning-making:

In the subjective and embellished telling of the past, the past is constructed — history is made. History is judged to be true or false not solely with respect to its adherence to empirical fact. Rather, it is judged with respect to such narrative criteria as “believability” and “coherence.” There is a narrative truth in life that seems quite removed from logic, science, and empirical demonstration. It is the truth of a “good story.” (1993, p.28)

The Life-as-Project approach doesn’t follow this kind of “narrative truth” because logic, science, and empirical demonstration are useful tools to discover new insights from our pasts.

McAdams also used the term “Narrative Identity” to emphasize the difference between his theoretical approach and Erik Erikson’s concept of Identity in his 2006 book The Person: A New Introduction to Personality Psychology (2006, fourth edition).

According to Erik Erikson, beginning in adolescence and young adulthood modern people are faced with the psychosocial challenge of constructing a self that provides their lives with unity, purpose, and meaning. For the first time in the life course, these questions become problematic, and interesting: “Who am I?” “How do I fit into the adult world?” As we address these questions, Erikson maintained, we begin to construct what he called a configuration, which includes constitutional givens, idiosyncratic libidinal needs, significant identification, effective defenses, successful sublimations, and consistent roles” (Erikon, 1959, p.116) The identity configuration works to integrate “all identifications with the vicissitudes of the libido, with the aptitudes developed out of endowment, and with the opportunities offered in social roles.”

(2006, p.405)

McAdams considered different contents for identity configuration.

What might this unique “configuration” of identity look like? In my own theoretical writing. I have argued that the identity configuration of which Erikson speaks should be seen first and foremost as an integrative life story that a person begins to construct in late adolescence and young adulthood. A growing number of personality, social, cognitive, developmental, and clinical psychologists today describe identity in terms of a narrative or story that people construct in a social world. Following Singer (2004) and others, we will use the term narrative identity to refer to the internalized and evolving story of the self that a person consciously and unconsciously constructs to bind together many different aspects of the self. Narrative identity provides a person’s life with some degree of unity, purpose, and meaning. (2006, p.405)

It’s clear that McAdams emphasized the latest development of psychological research, which lies outside the scope of traditional developmental theories, such as Erikson’s theory, which still considers the concept of “libido.”

In general, McAdams’s approach utilized narrative psychology to explain the power of life stories for self and identity.

Imagoes, Power, and Love

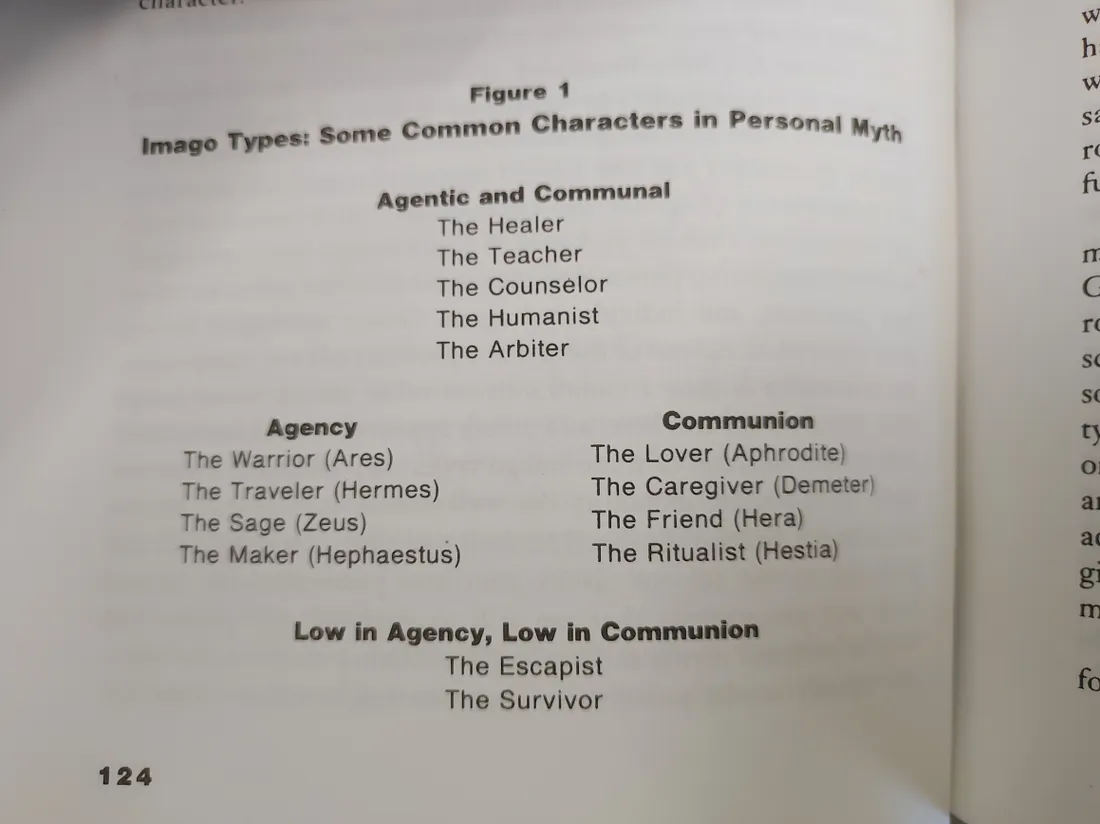

McAdams called the characters that dominate our life stories imagoes.

In seeking patterns and organization for identity, the person in the early adult years psychologically pulls together social roles and other divergent aspects of the self to form integrative imagoes. Central conflicts or dynamics in one’s life may be represented and played out as conflicting and interacting imagoes, as main characters in any story interact to push forward the plot. (1993, p.122)

The concept of Imago appears to serve as a bridge between Self and Social Roles.

An imago is a personified and idealized concept of the self. Each of us consciously and unconsciously fashions main characters for our life stories. These characters function in our myths as if they were exaggerated and one-dimensional form; hence, they are “idealized.” Our life stories may have one dominant imago or many. The appearance of two central and conflicting imagoes in personal myth seems to be relatively common. (1993, p.122)

Where do imagoes come from?

Imagoes exist as carefully crafted aspects of the self, and they may appear as the heroes or villains of certain chapters of the life story. They are often embodied in external role models and other significant persons in the adult’s life. As out personal myths mature, we cast and recast our central imagoes in more specific and expansive roles. We come to understand ourselves better by a comprehensive understanding of the main characters that dominate the plot of our story, and push the narrative forward. With maturity, we work to create harmony, balance, and reconciliation between the often conflicting imagoes in our myth. (1993, p.123)

Now we can see a typology of imago. See the picture below.

McAdams used the dimensions of agency and communion to categorize Imago types, as they represent two central themes in stories and personal myths.

A keyword associated with the agency theme is Power.

In literature, drama, song, and verse, there are many different kinds of characters who act, think, and feel in agentic ways. These are characters who seek to conquer, master, control, overcome, create, produce, explore, persuade, advocate, analyze, understand, win.

They are described by such adjectives as aggressive, ambitious, adventurous, assertive, autonomous, clever, courageous, daring, dominant, enterprising, forceful, independent, resourceful, restless, sophisticated, stubborn, and wise, among many others. (1993, p.134)

A keyword associated with the communion theme is Love.

There are numberless characters who act, think, and feel in communal ways. Oriented toward love and intimacy, these are characters who seek to unite with others in passionate embrace, who love and care for others, who nurture, cooperate, encourage, communicate, and share with others. They work to provide settings for love and intimacy, and to cultivate the best in human intercourse.

They are described by adjectives such as affectionate, charming, altruistic, enticing, gentle, kind, loyal, sensitive, sociable, sympathetic, and warm, among many others. (1993, p.148)

Power and love are the two great themes of stories, corresponding to the central psychological motivations in human life.

Agentic Mindset and Communal Mindset

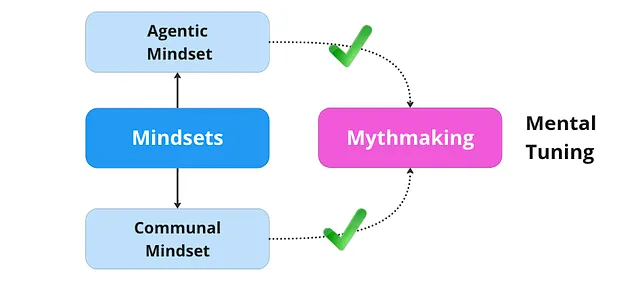

In McAdams’ approach, I found a pair of themes called the Agentic and Communal characters. These two themes can be considered as distinct mindsets.

According to McAdams, “An especially agentic person is driven by recurrent desires for power and achievement. The power motive is a desire for feeling strong and having impact on the world. The achievement motive is a desire for feeling competent and doing things better than others do them. Power and achievement motives, although both agentic, differ from each other in important ways.” (1993, p.282)

On the other hand, the communal character is associated with intimacy motivation, “The intimacy motive is a recurrent desire for warm, close, and sharing interaction with other human beings…Intimacy motivation is associated with an especially communal friendship style…Some recent research suggests that intimacy motivation may be implicated in health and psychological well-being. Many theories of personality and psychotherapy suggest that the capacity for intimacy is a hallmark of adjustment and maturity in life.” (1993, p.287, pp.288–289)

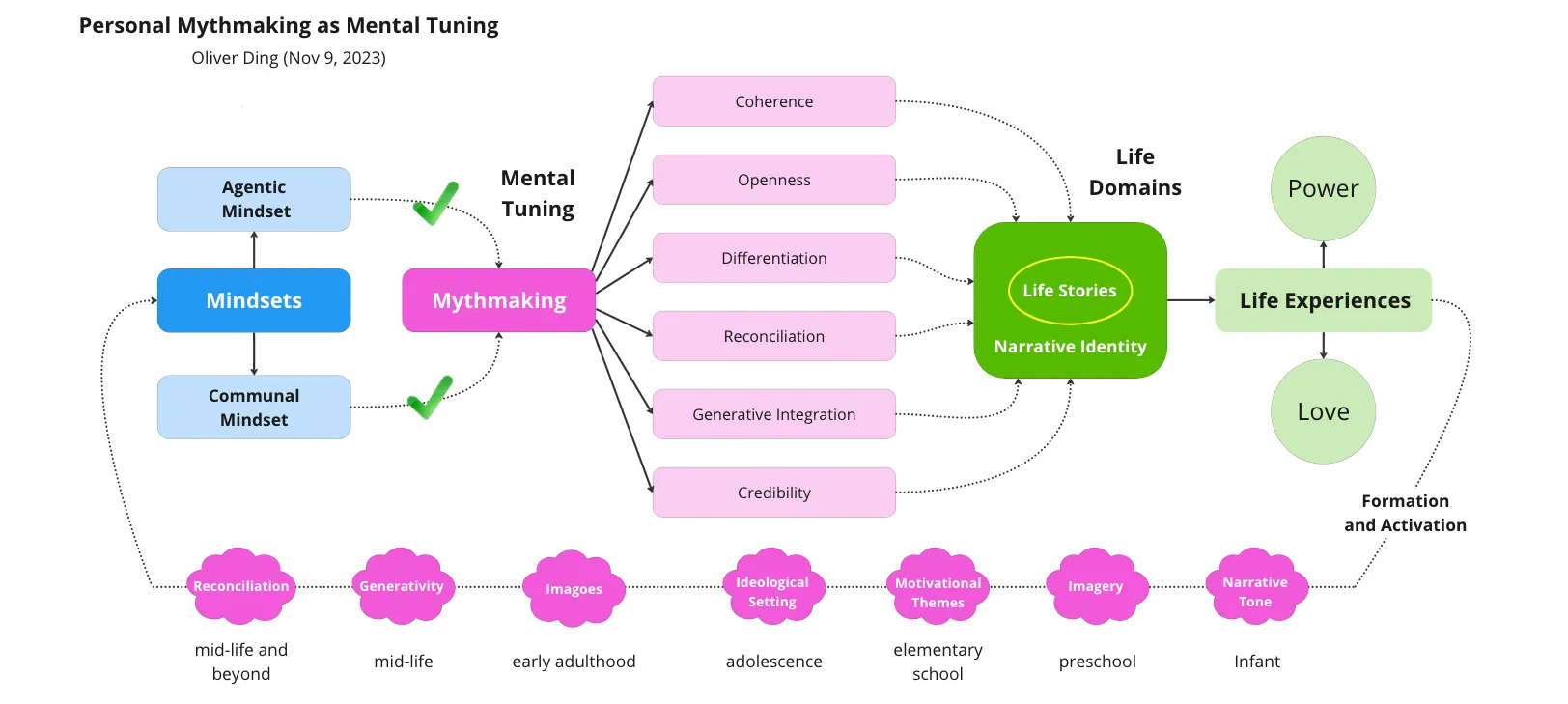

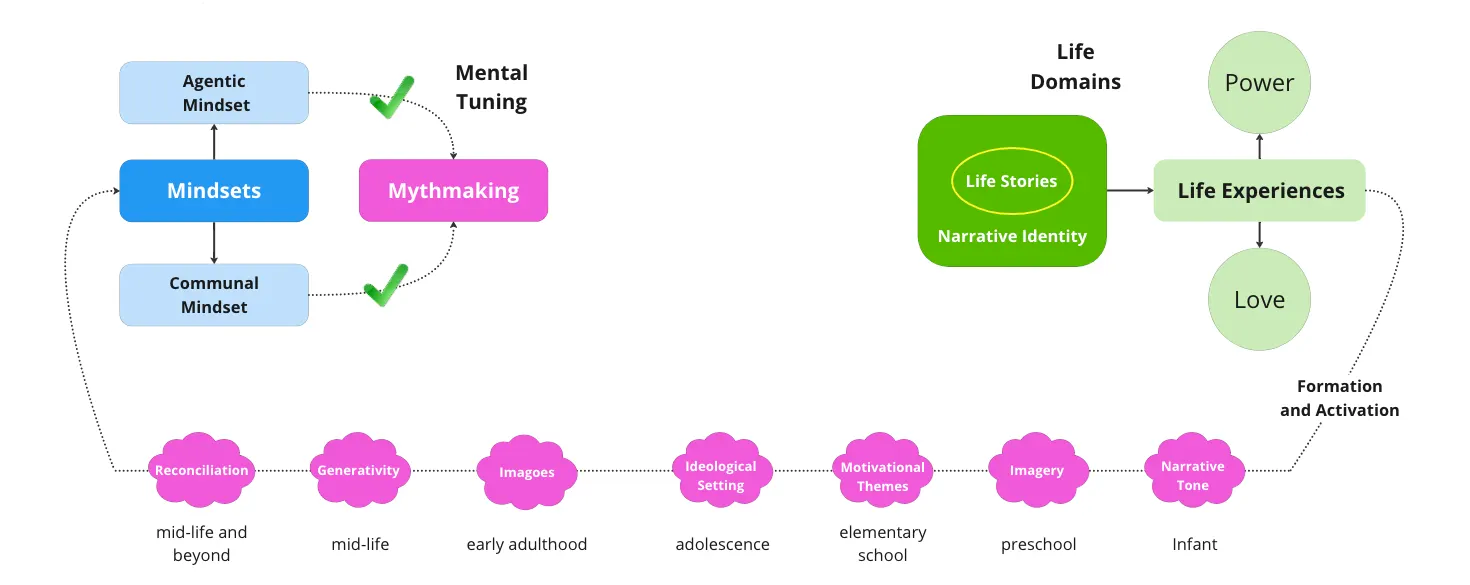

Based on this idea, I used the Mental Tuning framework to represent McAdams’s approach.

The above diagram has three parts. The blue part represents the Mindsets and Mental System. The green part represents the Behavioral System. The pink part represents the connection between the Mental and the Behavioral Systems.

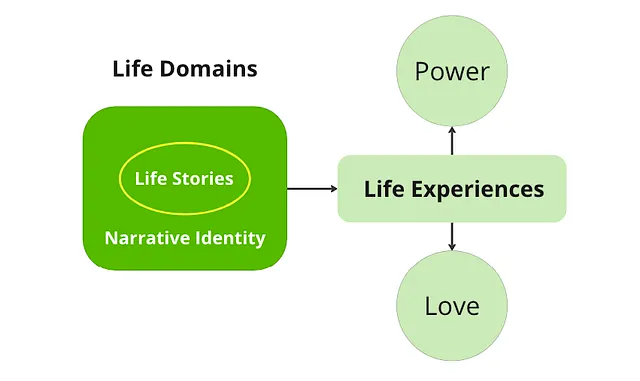

“Life Domains” and “Life Experiences” are used to represent the Behavioral System. McAdams’s approach focuses on Life Stories and Narrative Identity. I also use Power and Love as two keywords for Life Experiences.

The concept of “Life Experiences” serves to emphasize the subjective aspect of the Behavioral System. This aspect is crucial to understanding the Formation and Activation of Mindsets.

McAdams developed an explicit developmental framework for personal mythmaking. Several significant elements impact personal mythmaking, each linked to a particular developmental period (1993, pp.270–271).

- Narrative tone originates in infant attachment

- Imagery originates in preschool play and imagination

- Motivational themes trace back to the elementary-school years

- The ideological setting is laid down in adolescence

- Imagoes begin to form in early adulthood

- Generativity script becomes more salient in mid-life and beyond

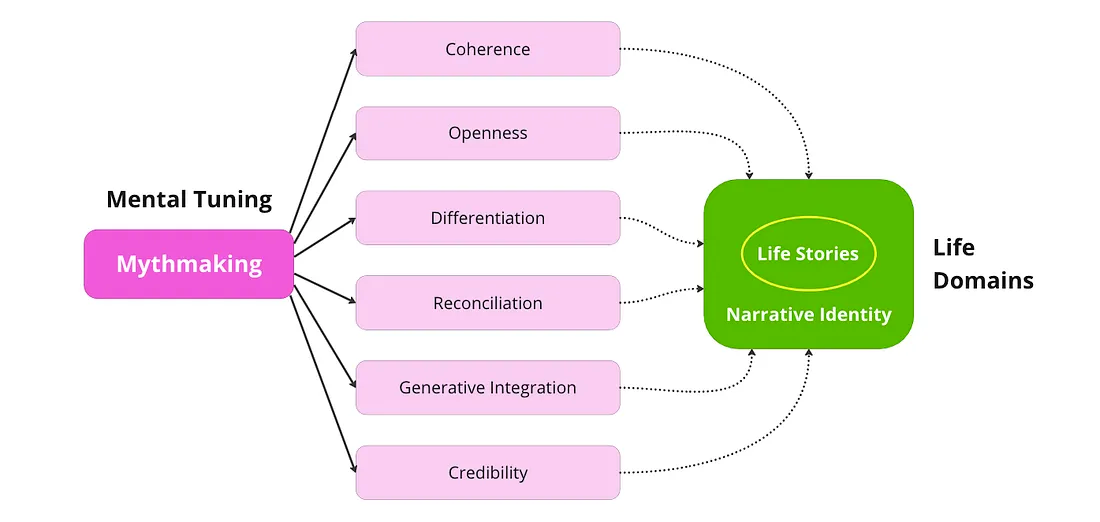

The middle part of the new framework is defined by a new term called “Mental Tuning.” In general, “Mental Tuning” refers to active self-regulation strategic techniques aimed at improving particular psychological functions related to Life Domains.

McAdams pointed out that there are two different kinds of progressive change in personal mythmaking:

- Developmental change is oriented toward the future.

- Personological change is oriented toward the past rather than the future.

Personological change is a profound and difficult kind of identity transformation that is typically the subject of intense, in-depth psychotherapy. Developmental change could be understood through six criteria: Coherence, Openness, Differentiation, Reconciliation, Generative Integration, and Credibility (1993, pp.272–273).

- The first two criteria — coherence and openness — form a dialectical tension in identity… Ideally, your personal myth should strike a balance between the two, but the balance is likely to be weighted differently at different points in development.

- A similar kind of dynamic may be identified for the criteria of differentiation and reconciliation. A mature personal myth should display many different parts and aspects…You may need to refashion the story in a way that brings the different characters together in some manner, or in a way that makes their oppositions even starker, so as to find unity and purpose in the dialectical contradictions of mid-life.

- As you move from adolescence through young adulthood and into mid-life, generative integration becomes an increasingly important criterion in personal mythmaking… generative integration has no worthy “opposite”. It simply grows steadily in importance over time.

- Equally steady is the sixth criterion, credibility. But the importance of credibility in myth does not generally increase or decrease across the life span…The good and mature personal myth is grounded in social and personal reality. It is what you have created from the real resources you have been given. Mature identity does not transcend its resources; it is true to its context. The myth and the mythmaker must be credible if we are to live in a credible world.

McAdams highlighted that the dialectical contradiction between opposite themes plays a significant role in personal mythmaking.