The Dialectic Room: A Meta-diagram for Innovation

Playing with Pairs of Opposite Themes

by Oliver Ding

Originally written on January 11, 2022; updated on October 30, 2025

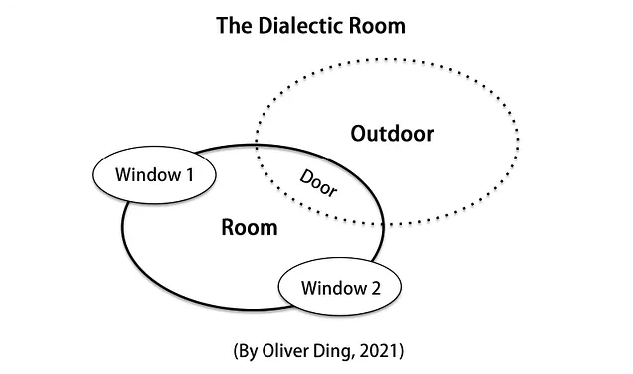

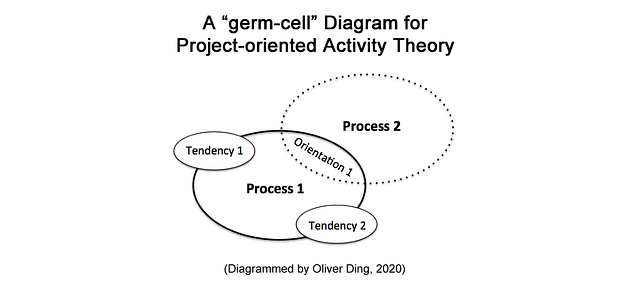

The diagram above is a meta-diagram designed to apply dialectical logic to manage structural tensions. Its origin lies in the “germ-cell” diagram of Project-oriented Activity Theory (see the diagram below).

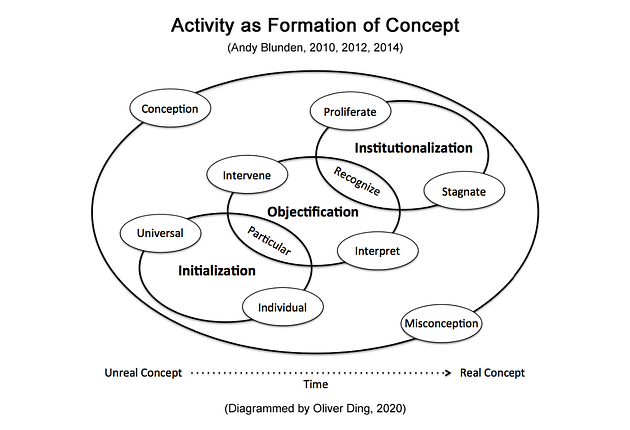

On January 3, 2021, I published an article titled Activity U (VIIII): Project-oriented Activity Theory, which introduced Andy Blunden’s Project-oriented theoretical approach to activity with a series of diagrams.

To develop the theoretical foundation of “Project as a unit of Activity,” Blunden draws on Hegel’s logic and Vygotsky’s theory of concept as key theoretical resources. This process is documented in three books: An Interdisciplinary Theory of Activity (2010), Concepts: A Critical Approach (2012), and Collaborative Projects: An Interdisciplinary Study (2014).

One of the three central notions in Blunden’s approach is the “germ-cell.” According to Blunden, “…in order to understand a complex process as an integral whole or gestalt, we have to identify and understand just its simplest immediately given part — a radical departure from the ‘Newtonian’ approach to science based on discovering intangible forces and hidden laws” (2020).

Blunden has provided several successful examples of applying the germ-cell concept in theory building, such as Hegel’s formulation of ideas, Marx’s Capital, and Vygotsky’s five ideas.

Can the germ-cell concept be applied to diagramming in the social sciences?

I accepted this challenge with a concrete task: designing a series of diagrams for Blunden’s Project-oriented Activity Theory using a germ-cell diagram. This task aligns closely with my ideas about “meta-diagram, diagram, and diagram system.” A germ-cell diagram is a special type of meta-diagram that can easily generate a diagram system with a consistent intrinsic spatial logic.

A typical diagram system is structured as a network of diagrams that supports a multi-level analysis framework. Building such a system presents several challenges, two of which are highlighted below.

First, designing a consistent spatial logic across levels. To address this challenge, a germ-cell diagram provides an effective approach. It allows for the creation of a spatial logic that can be applied consistently across all levels of the multi-level diagram system. In other words, a single spatial logic governs the entire system, as it represents the structure of the whole.

Second, validating the diagram with real examples. The next challenge is to test the diagram using concrete instances. For example, the diagram below represents the core idea of Project-oriented Activity Theory and is an expanded version of the original germ-cell diagram. It also serves as a strong validation of the germ-cell concept.

In the case of the Dialectic Room, the underlying theory already embodies the germ-cell logic, which makes my task relatively straightforward. My role was to translate textual descriptions into visual diagrams.

What was my strategy for this translation?

I transformed the abstract theoretical concepts into an ecological metaphor that captures the spatial logic.

An Ecological Metaphor for Tough Situations

The Dialectic Room is an ecological metaphor. Here, the term ecological metaphor does not refer to a conceptual metaphor in the sense used in cognitive linguistics. Instead, it describes a structural and spatial analogy that models thinking or activity through ecological relationships. In other words, it is not about mapping concepts from one domain to another, but about representing a systemic logic that connects parts and wholes, inside and outside, tension and transformation.

We can consider a tough situation with structural tension as a room with two windows and one door.

- a tough situation = a room

- a structural tension = a pair of Opposite Themes = two windows

- a final action = a door

A room is a container that separates the inside space from the outside space. There are several kinds of actions people can perform within a room. Here, I focus on a particular type of action: connecting the inside space to the outside space. Let’s call this action “Process.”

The two windows serve as interfaces that represent two “Tendencies.” Window 1 refers to Tendency 1, while Window 2 refers to Tendency 2. Each window provides its own view of the outside space.

Finally, there is a door that allows people actually to leave the room. The door refers to “Orientation,” which represents the direction of a real action — an act of moving from the inside space to the outside space.

Once you step into the outside space, you can treat it as a new room and repeat the same diagram.

This expresses a special kind of spatial logic. Terms such as “Process,” “Tendency,” and “Orientation” are textual placeholders for describing this logic. From the perspective of my diagram theory, a pure meta-diagram does not require text. For instance, the Yin-Yang symbol, or Taijitu, is a meta-diagram — can you find any text within it? However, we can add textual placeholders to a pure meta-diagram in order to make its structure easier to describe.

Structural Tensions

To use the Dialectic Room, you must first identify the structural tensions behind a tough situation.

Structural tensions can take many forms: boundaries, distances, differences, heterogeneity, contradictions, complementation, and so on.

If we can turn one or more structural tensions into creative opportunities, it becomes possible to discover pathways for life innovation.

The next step is to use text to describe structural tensions as Pairs of Opposite Themes, represented by Theme 1 and Theme 2. For example, I find many pairs of opposite themes from my career experiences:

- Public vs. Private

- Community vs. Family

- Non-profit vs. Profit

- Media vs. Action

- Creativity vs. Curativity

Public vs. Private refers to my public blogging before 2014 and my interest in personal private notes after 2014. I started paying attention to biography studies and found that many biography studies are based on personal private notebooks. This dimension also led to personal knowledge and private learning groups.

Community vs. Family refers to my active online community activities before 2014 and the complexity of my family activities after 2014. This dimension is about work/life balance.

Non-profit vs. Profit refers to my non-profit projects, such as online communities, and my work on web/mobile app development and design.

Media vs. Action refers to my early career in the media business and creative marketing communication, and my recent action-centered product design and theoretical approach development.

Creativity vs. Curativity refers to my learning on creativity studies and my own theoretical approach to curativity.

The Dialectic Logic for Personal Innovation

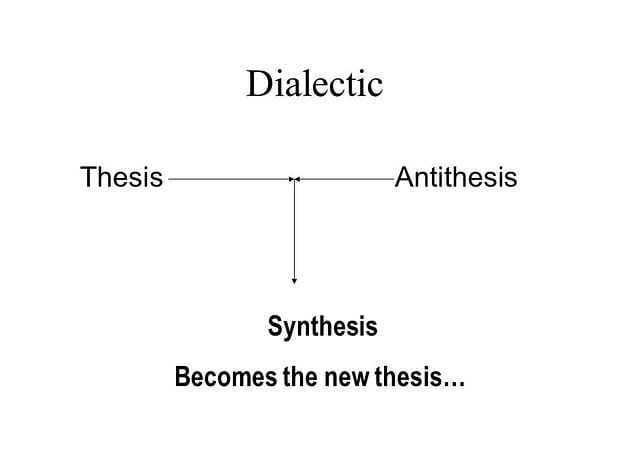

We can adopt Hegel’s Dialectic (see the diagram below) to understand Pairs of Opposite Themes. We can consider Theme 1 as the Thesis and Theme 2 as the Antithesis. By adopting Hegel’s Dialectic, the fit between Theme 1 and Theme 2 means finding the Synthesis between Thesis and Antithesis.

It is important to note that this is just one of many possible approaches. Other frameworks or methods can also be used to think about and resolve conflicts between themes. The purpose here is not to claim Hegel as the only lens, but to illustrate a way of fitting opposite themes together and discovering new opportunities for personal innovation.

Now, let’s apply Hegel’s theory of Concept to understand Themes, using my own career reflection as an example.

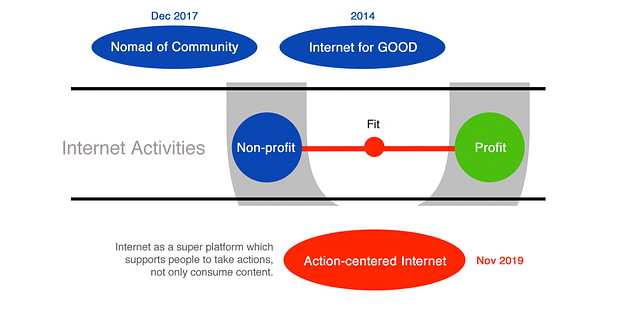

In November 2019, I did a career reflection and discovered a new career theme by fitting a pair of opposite themes together. The reflection focused on my internet activities from 2004 to 2014. I noticed a Pair of Opposite Themes in my experience: my daily job involved working on a web/mobile startup, which was a profit-driven business, while I spent most of my spare time in non-profit online communities focused on social learning, open education, free culture, and similar activities.

At the time, I didn’t pay much attention to the contrast between these two areas. I simply thought of them as “daily work vs. spare time work.” For example, I developed several themes from my non-profit online activities. In 2014, I used the theme Internet for GOOD to highlight the social impact of my internet activities during 2004–2014. In December 2017, I used the theme Nomad of Community to highlight the consistency of my community-building efforts, as I was always joining or starting new communities.

In November 2019, I realized that I could fit the theme of Non-profit and the theme of Profit together. I coined the term Action-centered Internet to highlight the common thread between them. I found that my daily job involved creating products and tools that enable people to take action. Clearly, I prefer working on things that support people’s actions rather than merely consuming content or entertainment.

Using Hegel’s terms, the theme Profit is the Thesis, the theme Non-profit is the Antithesis, and the theme Action-centered Internet is the Synthesis. We should note that Action-centered Internet also becomes a new Thesis, pointing toward a new Pair of Opposite Themes: “Action | Content.”

Since a new career theme breaks the old frame of our career experience, it can lead to personal innovation. The theme Action-centered Internet guided me to explore further potential directions for Internet-based innovation.

Moreover, the opposite themes “Action vs. Content” later led to a new Synthesis: Activity Theory — a theory about human activity and the curation of actions. As a theory, it is primarily Content, which I learned by reading papers, books, and watching videos. Since its main object is human activity, I practiced its principles and concepts in several ways: by taking real actions, engaging in projects, designing new tools to support activities, and even exploring new types of activities.

This process also led me to discover Andy Blunden’s approach to activity, and through Blunden, I explored Hegel’s theory of concept.

In 2021, after finishing Project-oriented Activity Theory, which introduced Blunden’s ideas, I applied Hegel’s concepts to develop the Career-fit framework for understanding personal innovation.

According to Andy Blunden, “As Hegel explained, every concept exists as Individual, Particular and Universal. These three moments of the concept are never completely in accord. There is always a measure of dissonance between them, and this is manifested in the dynamics of the concept. What an individual means when they use the word is never quite the same as the meaning produced in any other context.” (2012, p.295)

Although Themes are not the same as concepts, we can borrow Hegel’s approach to understand and navigate the complex relationships between them. If we want to fit several pairs of opposite themes, we can consider three sub-dimensions: Individual, Particular, and Universal.

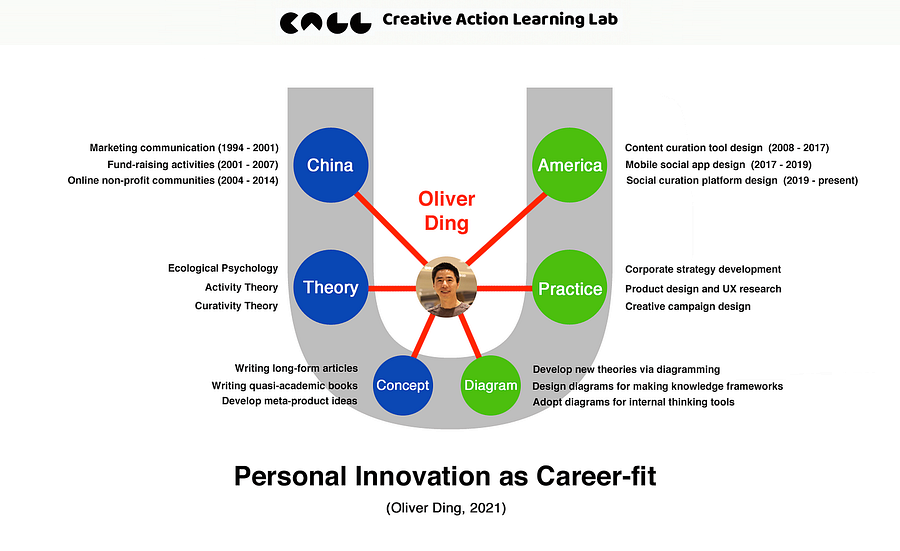

Inspired by these dimensions, I conduct a case study of my own career-fit by selecting three pairs of opposite themes from my past twenty years of work experience:

- Universal: China vs. America

- Particular: Theory vs. Practice

- Individual: Concept vs. Diagram

See the diagram below.

The first pair, “China vs. America,” reflects cross-cultural work and life experiences, highlighting significant differences between the two countries. The second pair, “Theory vs. Practice,” reflects cross-disciplinary knowledge and experience, emphasizing the gap between academic knowledge and practical work activities. The third pair, “Concept vs. Diagram,” reflects cross-domain cognitive experience. According to cognitive scientist Barbara Tversky, concepts involve linguistic thought, whereas diagrams involve spatial thought.

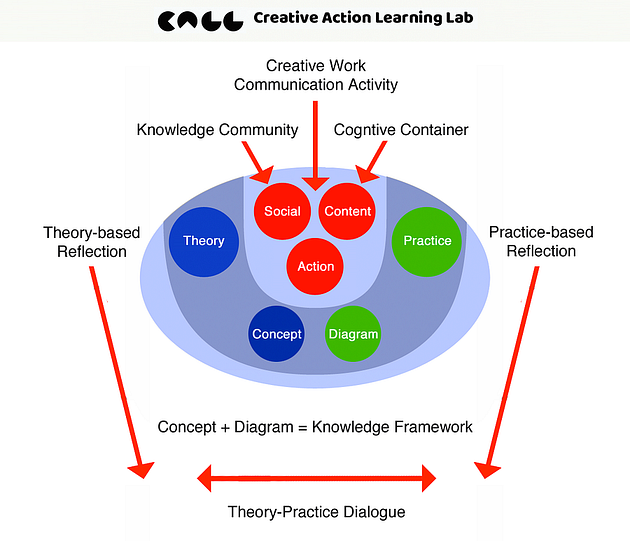

My strategy focused primarily on the Particular and Individual levels. From 2019 to 2021, the Theory-Practice fit and the Concept-Diagram fit became my main focus. (See the diagram I created in 2021 below.)

The Theory vs. Practice fit is described with three movements:

- Practice-based Reflection: building rough models with intuition.

- Theory-based Reflection: improving models with theoretical resources.

- Theory-Practice Dialogue: turning models into frameworks and testing them with case studies.

The article Platform Innovation as Concept-fit offers a real example of these three steps. The Concept-fit framework was developed within three months.

The Concept vs. Diagram fit is expressed with a simple formula:

- Concept + Diagram = Knowledge Framework

Although this formula was formally defined in the HERO U framework I developed in 2020, I had actually been applying it consistently in my creative work since 2017.

You can find more details in the original article Personal Innovation as Career-fit.

Hegel’s theory does not provide concrete details for finding a solution for a particular Synthesis; the actual operational actions must be discovered in the real world. By developing the Concept-fit framework for platform innovation and the Career-fit framework for personal innovation, I realized that these operational actions (what I call “fit”) can be studied through domain-specific case studies. This insight later led to the notion of “Activity Analysis,” which became the primary theme of the Activity Analysis Center.

The Dialectic Logic for Business Innovation

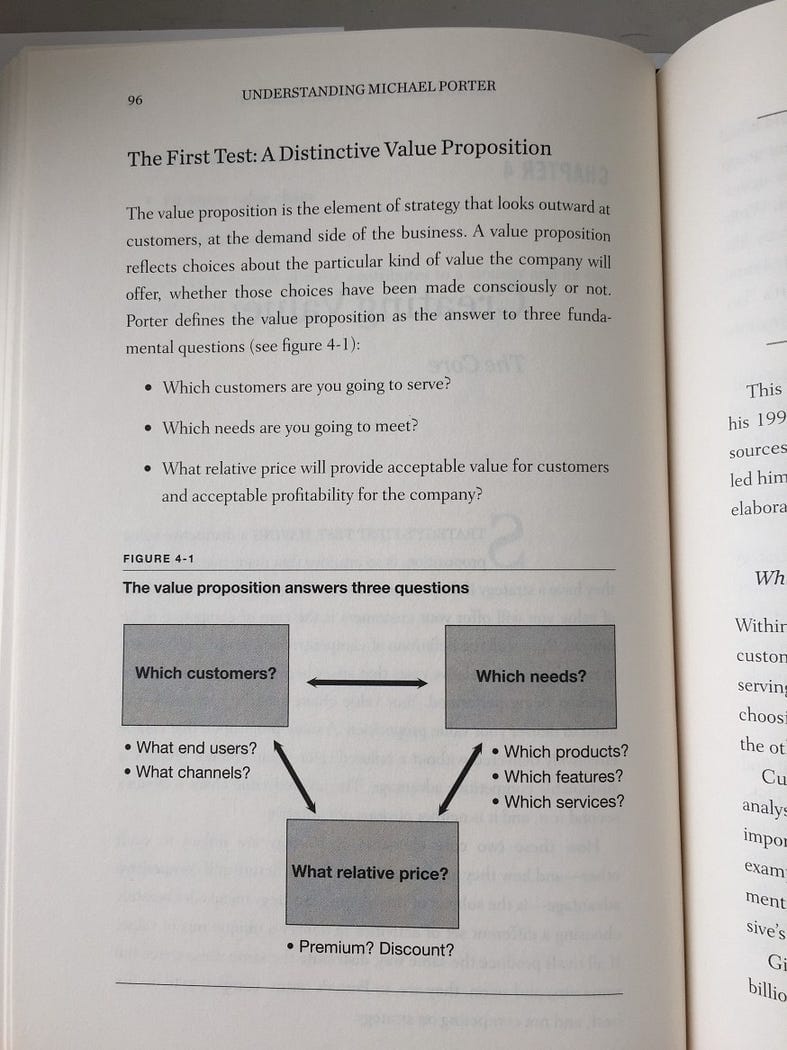

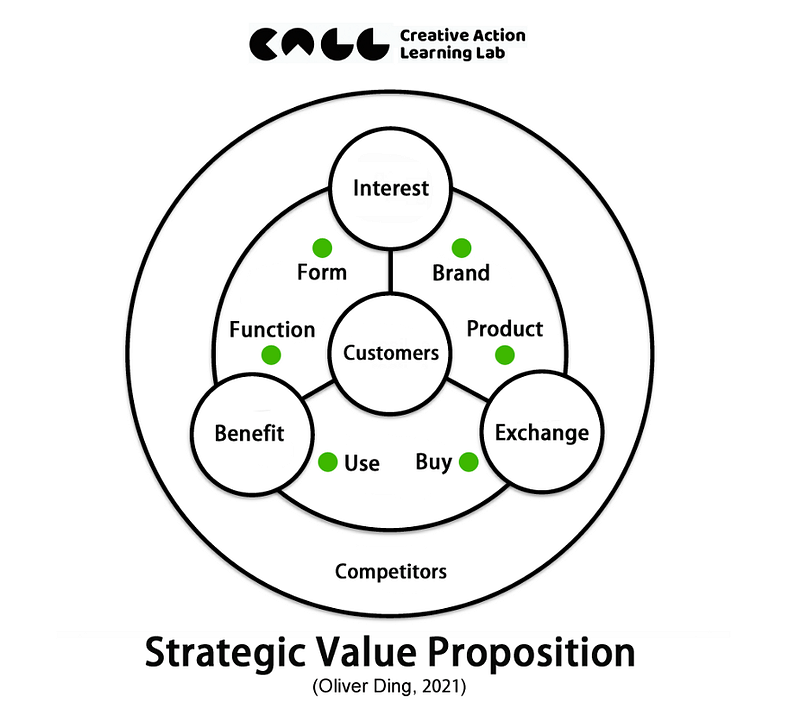

On July 12, 2021, I published a post titled D as Diagramming: Strategic Value Proposition and shared a diagram inspired by Michael Porter’s ideas on value proposition.

Porter defines the value proposition as the answer to three fundamental questions:

1. Which customers are you going to serve?

2. Which needs are you going to meet?

3. What relative price will provide acceptable value for customers and acceptable profitability for the company?

I expanded Porter’s framework using the Tripartness meta-diagram and named the outcome Strategic Value Proposition.

Tripartness is one of a set of meta-diagrams I have designed over the past years. It can be expanded into a Diagram Network.

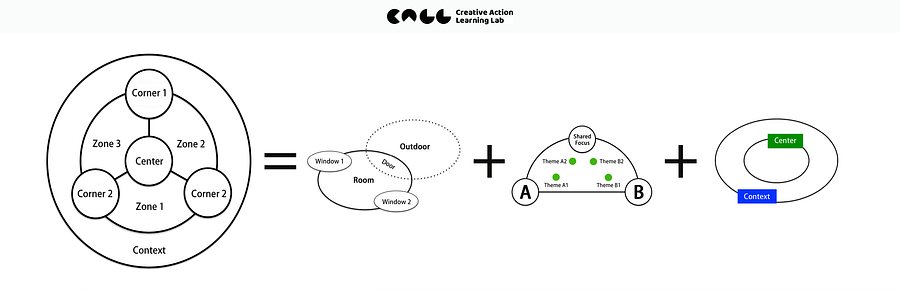

The diagram above shows the process of diagram blending. The Tripartness diagram has two pairs of concepts:

- Corner and Zone

- Center and Context

To understand these concepts, we can use the following three diagrams:

- Corner: The Dialectic Room

- Zone: The Interactive Zone

- Center and Context: The Hierarchical Loops

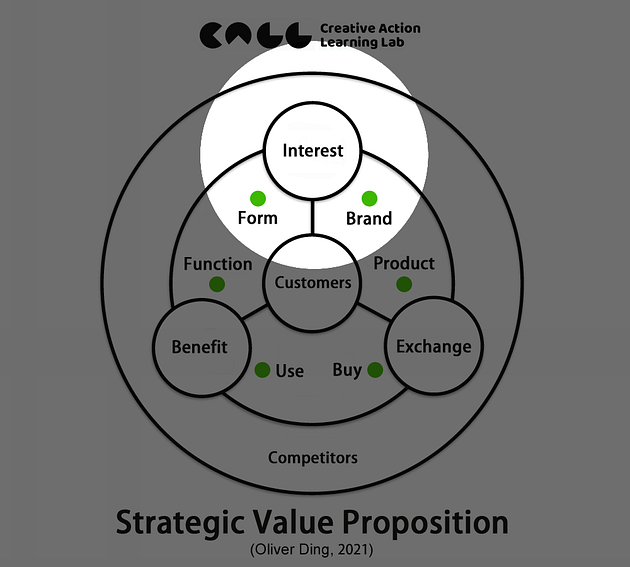

For the Tripartness Diagram, each Corner can be expanded to a Dialectic Room. For example, the picture below highlights a Corner of the Strategic Value Proposition diagram.

There are three words in this corner:

- Interest: the core of the corner

- Form and Brand: two themes

The Interest Corner refers to the process by which customers perceive value. Initially, a potential customer does not own or use a product, so they can only perceive information about it from their surrounding environment. There are two types of information:

- Form: visual cues such as the product’s look, structure, dynamics, size, color, etc. These offer clues about the product’s functions — essentially, what does it look like?

- Brand: narrative information such as emotions, cultural values, stories, rhetorical messages, rankings, and word of mouth. This offers clues about the product’s reputation — can I trust it?

If a firm can provide both types of information effectively, it can attract attention and stimulate interest in purchasing.

Now, let’s adopt the Dialectic Room diagram to make a new diagram for understanding the Interest corner deeply.

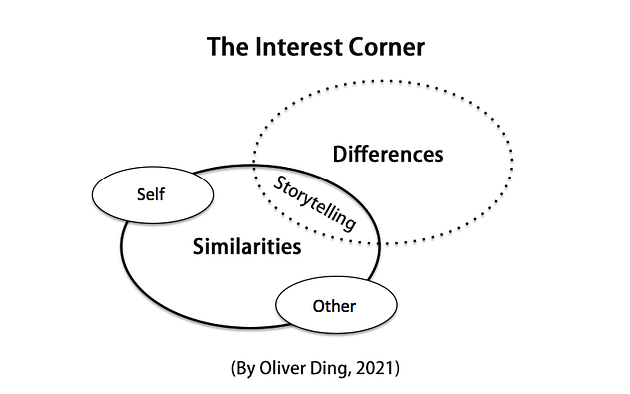

To understand the Interest Corner more deeply, we can apply the Dialectic Room diagram. Several concepts are highlighted:

- Self and Other

- Similarities and Differences

- Storytelling

This diagram can be applied to analyze both customers and competitors; here, I focus on customers, though readers can apply the same logic to competitors.

For customers, the room represents their present life, which is full of similarities. Self refers to the potential customer, and Other refers to people or entities in their surrounding environment. The customer receives the two types of information (Form and Brand) from the Other, either from the firm or other people. If the information is too similar to the customer’s current life, they will not be interested.

The firm must create a difference to move the customer from their present life to a new life world. The strategy of storytelling can focus on Form, Brand, or both.

If the firm cannot differentiate through form, it can do so through brand, by highlighting unique cultural values or other distinguishing features.

Let’s see two examples.

The Chobani Flip illustrates the first strategy of making a difference through Form. The company designed a new type of yogurt container that allows consumers to flip the smaller part to pour the topping into the yogurt, creating a unique product experience.

In contrast, the Make Love Not War T-shirt exemplifies the second strategy of differentiating through Brand by leveraging cultural value. Consumers purchase this T-shirt because they resonate with and embrace the meaning behind the message.

You can find more details from the original article: D as Diagramming: The Dialectic Room and Value Engagement.

Just for fun…

If you don’t have any tough situations in your life, you can still play the Dialectic Room with pairs of opposite themes. It works as an intellectual game too!

On October 30, 2025, I engaged in a conversation inspired by a LinkedIn post. A friend shared a diagram and proposed a new term called Service Propositions:

The concept “use cases” is problematic. It assumes people have an implicit desire to use something or perform a one-time action. Use cases drastically narrow issues to very discrete human-technology interactions. Last, use cases hyperfocus on the transactional challenge of people using a feature that could be monetized.

A better alternative is “service propositions.” It suggests that people have the agency to respond to an offering. It considers the socio-technical complexity with more people’s roles (e.g., employees) and extended touchpoints in time. And considers an integrated challenge of economic viability.

I commented below with an attached diagram.

This is a very interesting idea. However, I perceive a conceptual tension.

“Use cases” can describe how people actually interact with a product in real-world contexts, whether the usage aligns with the designer’s intended design (designed) or emerges from users’ own discovery (found). In this interpretation, use cases grant users a degree of agency, allowing them to uncover the affordances embedded in a product–situation loop. Many seemingly “misused” cases, in fact, reveal how users appropriate a product’s affordances in specific contexts, even when the final usage deviates from the designer’s original intentions.

In contrast, “service propositions” inadvertently emphasize the designer’s subjective intent, highlighting the designed mode of usage while leaving little room for found usages. Users have limited options with a given service proposition: they can either accept it or reject it.

Is this the distinction you want to make? Perhaps we should consider swapping the two terms in the argument to better capture this dynamic.

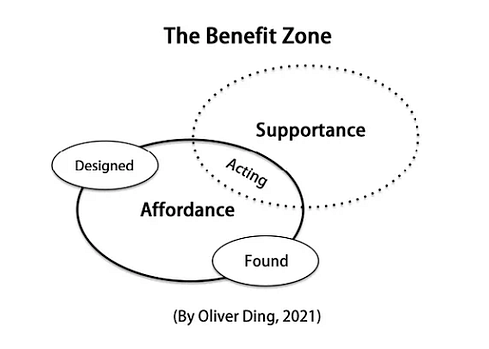

The attached diagram is the Benefit Zone, which I created in 2021 as part of the Strategic Value Proposition framework.

The diagram was based on the Dialectic Room meta-diagram, and I used it to discuss topics about tool-use actions, artifacts, and objects at the micro-level.

Anthropologist Tim Ingold (1993) argued a distinction between tools and artifacts, “A tool, in the most general sense, is an object that extends the capacity of an agent to operate within a given environment; an artefact is an object shaped to some pre-existent conception of form” (p.433) Ingold’s view focused on “non-designed” versus “designed” objects.

Ecological psychologist Harry Heft (2001) suggested that it’s better to use “Found Tools” to refer to “non-designed” tools, giving many examples, “…found tools, are identified and selected because of the suitability of their affordance properties in support of some action. Long grasses or stripped branches employed as probes in feeding at insect nests; broad, rigid leaves used to shovel insects into the mouth; stones used as hammers for cracking hard shells of nuts are examples. ” (p.341)

Why can stones be used as hammers for cracking hard shells of nuts?

Because the affordance properties of stones are relative to hammering. Stones are graspable, liftable, and resilient. Heft pointed out, “In short, animals that use materials for a range of purposes, from building materials to sponging liquid, are typically exploiting the affordance properties of these materials (Reed, 1993). These affordances have functional significance in a particular niche, and found tools are one source of meaningful information in the environment for an animal.” (p.341)

The concept of Affordance is only one side of the coin of Value; the other side is Supportance. The concept of Supportance offers a new perspective on social support and other social phenomena. It refers to the potential social support offered by social environments. For the present discussion, I want to emphasize the relationship between Affordance and Supportance. Sometimes, the actualization of affordances is decided by social support.

By using the Dialectic Room meta-diagram, the Benefit Zone diagram curates five concepts together: Affordance, Supportance, Found, Designed, and Acting. You can play the same game too.

By applying the Dialectic Room meta-diagram, the Benefit Zone diagram brings these ideas together, curating five key concepts: Affordance, Supportance, Found, Designed, and Acting. This approach transforms the abstract theory into a playful, operational tool — you can try this intellectual game yourself and explore the joy of conceptual curation.

Afterword

If you are interested in the theoretical considerations behind the Dialectic Room, here is a brief overview.

The Dialectic Room is a meta-diagram designed to operationalize dialectical thinking for practical analysis. Its structure is rooted in the ideas of Thematic Space Theory, where spatial logic and social cognition intersect. As a meta-diagram, its meaning comes from the intrinsic spatial logic — Process, Tendency, and Orientation — rather than from any specific social theory. In practice, the diagram helps integrate abstract concepts with concrete actions, transforming ideas into operational tools.

The underlying principles of the Dialectic Room can be traced to three sources. First, the Goethian germ-cell principle provides a scalable, multi-level structure: once you explore one space, you can repeat the same logic in the next. Second, the Hegelian engine guides the handling of conflicts: a structural tension framed as a pair of Opposite Themes moves from Thesis and Antithesis toward a Synthesis, bridging conceptual understanding and real action. Finally, the diagram itself represents a thematic space metaphor, where the Room, Windows, and Door correspond to a tough situation, structural tensions, and a path toward action, respectively. Together, these foundations make the Dialectic Room a practical and repeatable tool for exploring complex situations.

If you want to explore more, see the full discussion in The Dialectic Room: Theoretical Foundations.

- Originally written on January 11, 2022

- Updated on October 30, 2025

- 3,739 words