The Dialectic Room: Theoretical Foundations

The theoretical considerations behind the Dialectic Room meta-diagram

by Oliver Ding

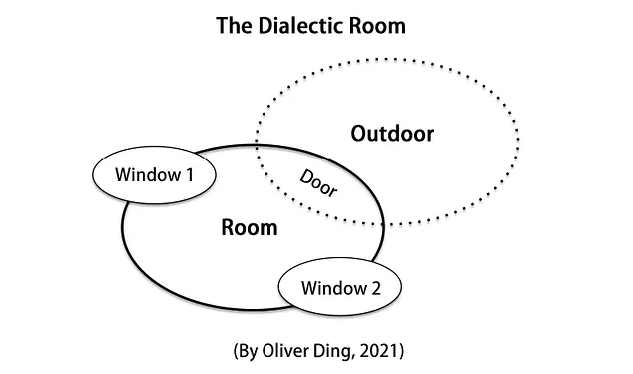

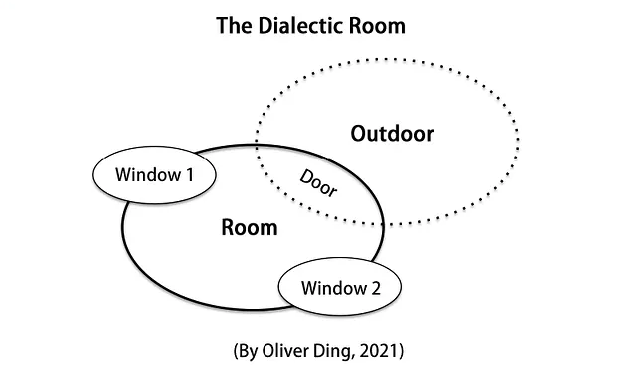

The Dialectic Room is a powerful meta-diagram designed to operationalize dialectic thinking for practical analysis. While its creation emerged from work on Project-oriented Activity Theory, its function as a meta-diagram allows it to stand independently of any specific theoretical approach. This assertion is central to Thematic Space Theory (TST), where the diagram’s structure is rooted in foundational ideas concerning spatial logic and social cognition. Consequently, the Dialectic Room is best understood as a specific illustrative case of TST in action.

As a meta-diagram — a special type of diagram that is an independent thing and does not have to represent an existing theory — the Dialectic Room’s specific meaning is intrinsically defined by its spatial logic (Process, Tendency, Orientation) and the measurable results of its application in practice. This complex interplay is vividly captured in the Dialectic Room.

This theoretical explanation aims to illuminate the intellectual considerations behind the diagram, helping readers understand how meta-diagrams, detached from specific theories, can curate various theoretical resources across different analytical levels, transforming into practical tools. This demonstration showcases the significant potential of Thematic Space Theory in bridging abstract philosophical concepts with concrete social practices.

1. The Goethian Foundation: Scaleless Analysis and the Germ-Cell

As a meta-diagram, the Dialectic Room can be used in many ways. It can be used at the individual level or for multi-level analysis. As the creator of the diagram, I'd like to point out that there is a theoretical commitment to its multi-level analysis methodology.

To understand a complex system with multiple levels, there are two ways of orientation: one is to treat each level as having its own patterns and that it should be analyzed with different models; we can say this approach is "Parts are Different." The other is the "germ-cell" principle, which refers to the primary form of a system that can represent the complexity of the whole system; it can be called "the Part contains the Whole."

The Dialectic Room embraces the latter approach.

The “germ-cell” principle has an official name, the concept of Urphänomen — a simple, archetypal phenomenon in which all the essential features of a complex process as a whole are manifested. It was introduced by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

In his 2010 book An Interdisciplinary Theory of Activity, Blunden traces the roots of Activity Theory to Goethe, Hegel, and Marx in order to present an immanent critique of Activity Theory and its contemporary version CHAT. The core of Blunden's argument is a theoretical-methodological issue: Unit of Analysis. For Blunden, the concept of “Unit of Analysis” should be understood as Goethe’s Urphanomen, which is also known as the ‘cell’. Blunden believes that the unit of analysis should be followed by an explanatory principle of “the part contains the whole”. In other words, if we want to understand a complex phenomenon, we should start with the most primitive form of the phenomenon. For activity theorists, if they agree that their theoretical roots lie in the ideas of Goethe, Hegel, Marx, and Vygotsky, then they have to respect this methodological criticism because the Urphanomen principle has been adopted by all of these predecessors.

Each year, I pick one idea I have learned as the idea of the year. The concept of Urphänomen and the notion of “germ-cell” are so powerful that I just picked them as my idea for 2020. According to Blunden, “…in order to understand a complex process as an integral whole or gestalt, we have to identify and understand just its simplest immediately given part — a radical departure from the ‘Newtonian’ approach to science based on discovering intangible forces and hidden laws” (2020)

Is it similar to fractal mathematics? According to Wikipedia, “a fractal is a self-similar subset of Euclidean space whose fractal dimension strictly exceeds its topological dimension. Fractals appear the same at different levels, as illustrated in successive magnifications of the Mandelbrot set.”

Now, let’s move from biology and mathematics to social science.

Can we apply the idea of “germ-cell” to diagramming for social science?

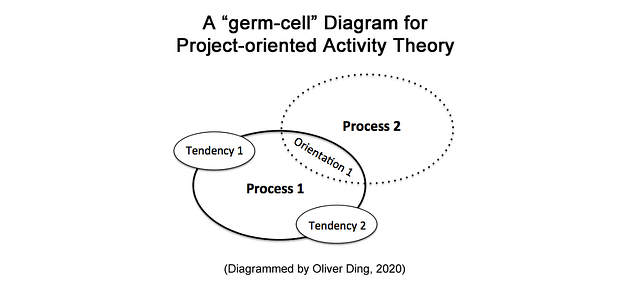

I took on this challenge with a concrete task: designing a series of diagrams for Blunden’s Project-oriented Activity Theory with a germ-cell diagram.

The germ-cell of a theoretical approach is defined as the smallest entity that can represent the whole of thinking across different levels of analysis. The challenge was to apply this philosophical concept to social science diagramming by designing a meta-diagram with an intrinsic spatial logic.

Since Blunden has given us several successful examples of applying the idea of “germ-cell” for social science, such as Hegel’s formulation of the idea, Marx’s Capital, and Vygotsky’s five ideas, my work seemed so simple. I just needed to translate Blunden's ideas into visual diagrams.

First, I made a "germ-cell" diagram for Blunden's approach.

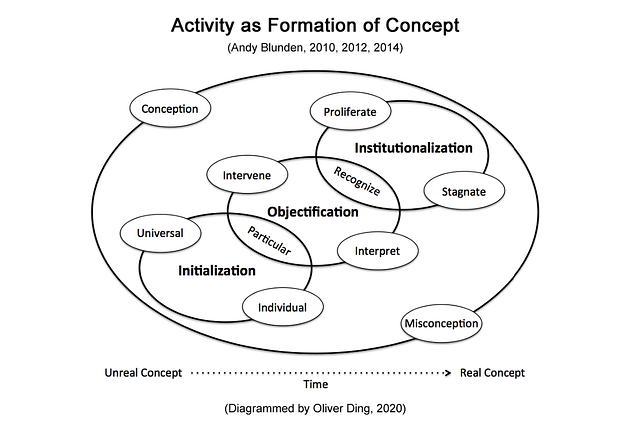

Second, I scaled it to multiple levels. See the diagram below, which shows the landscape of "Activity as Formation of Concept."

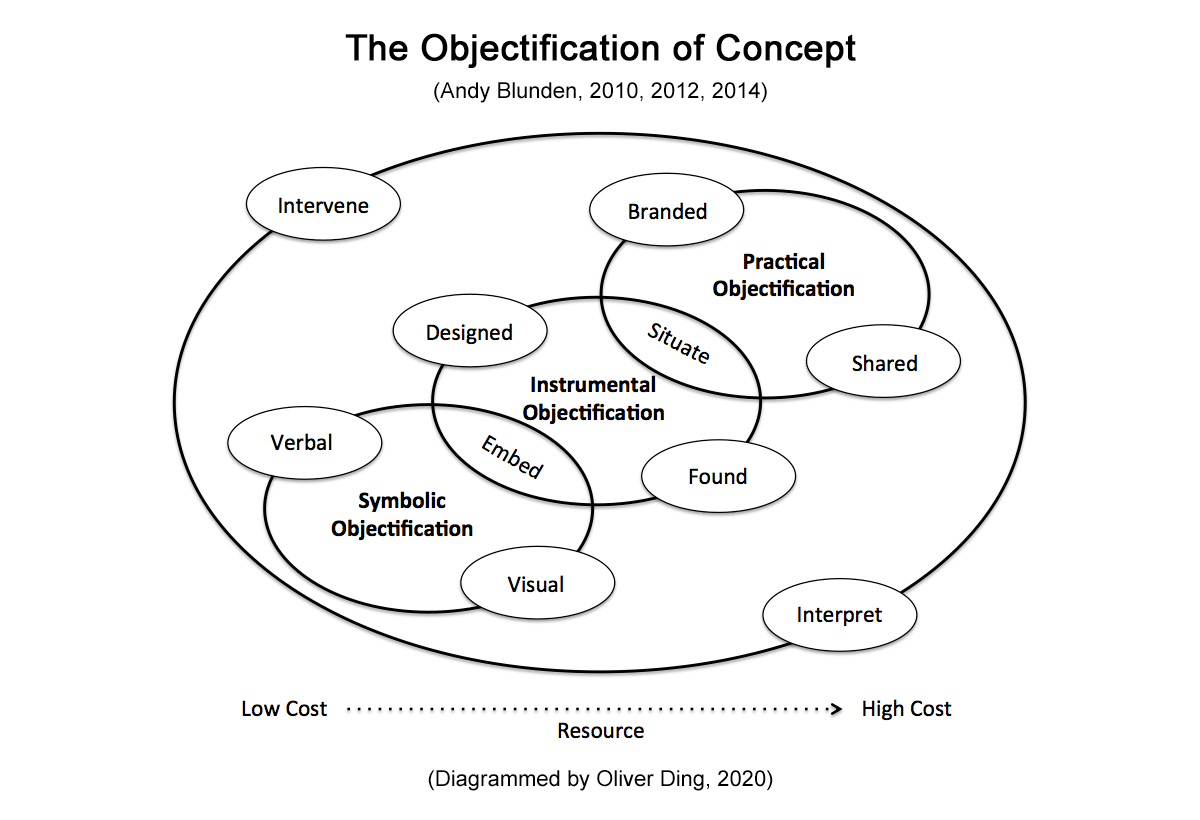

When zoomed in, the "Objectification" part becomes an independent diagram that retains the same spatial logic. See the diagram below.

More diagrams can be found in Case Study: TEDx as "Formation of Concept" [Activity Theory].

The unique design allows the "germ-cell" diagram to generate a multi-level analysis system with ease, effectively translating Blunden’s approach and Hegel’s ideas into visual form. The “scaleless” nature of the analysis is ensured by the structure’s built-in replicability: “Once you get into the outside space, you can consider the new space as a new room and repeat the diagram”.

2. The Hegelian Engine: From Logic to Practical Action

While the analytical framework is defined by spatial logic, the resolution of conflicts within the Dialectic Room is guided by Hegel’s dialectical logic. This approach extends analysis beyond abstract cognition and into the realm of practical action.

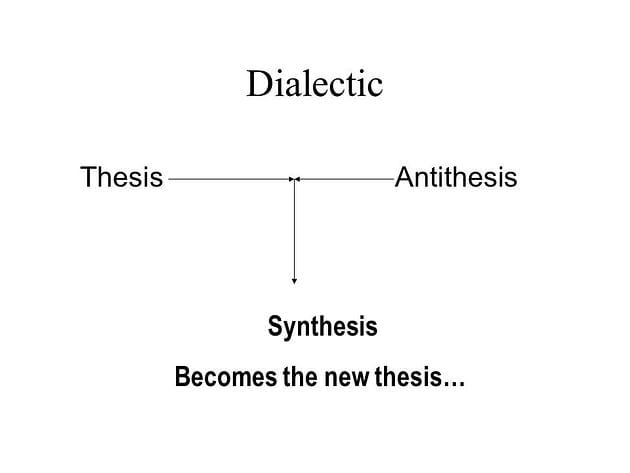

Hegel’s dialectical logic has been visualized in various ways by different authors. The diagram below is one such example.

While this diagram clearly represents the basic thesis–antithesis–synthesis structure of Hegel’s dialectic, which is sufficient for educational purposes, it does not highlight the crucial transformation of ideas from thought into practice, a central aspect of Hegel’s philosophy.

In a 1997 article titled The Meaning of Hegel's Logic, Andy Blunden points out that Hegel uses the "triad" structure to organize his philosophical system, without employing the "thesis - antithesis - synthesis" schema. According to Blunden:

The above demonstrates the "triad" of Hegel which runs through almost every sentence of the Science of Logic. Most people who are about to study Hegel, will have heard of "thesis - antithesis - synthesis". Actually, Hegel never used this expression. This may be because the expression tends to imply a reference to what I call "propositional algebra". Also, "thesis" and "antithesis", like "positive" and "negative" imply a specific kind of opposition, namely polarity, in which the "thesis" and "anti-thesis" can have no separate existence and a kind of symmetry which limits the concept unduly. Nevertheless, I think "thesis - antithesis - synthesis" fairly well sums up the form of Hegel's triad and we should not be ashamed to use it. (Source: marxists.org)

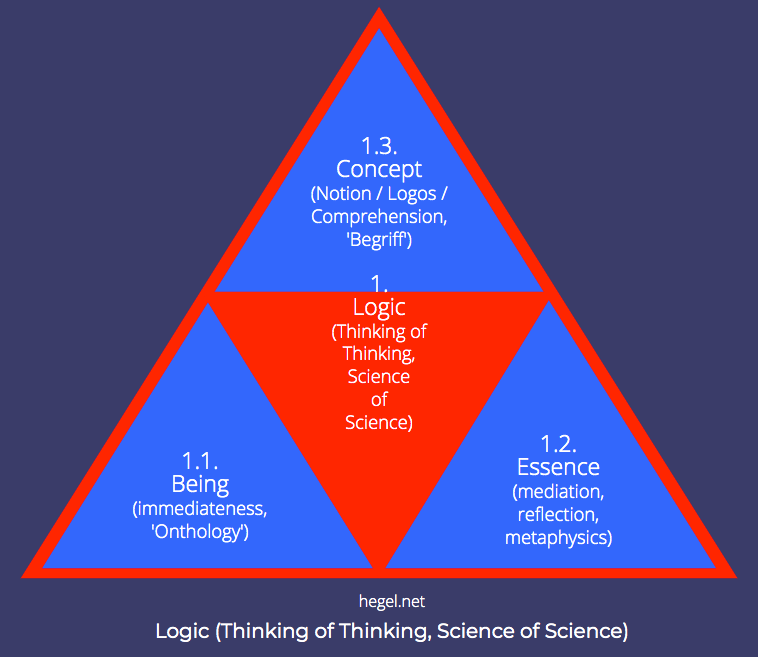

Similarly, some researchers use a visual triad to represent Hegel's works on Hegel.net. An example is shown below.

While this visual triadic style effectively illustrates the structural composition of Hegel's text, it fails to convey the core meaning of Hegel's idea, namely, how each concept lives through its own internal contradictions, which gradually build up and transform into the next concept. Moreover, this style tends to evoke the image of a purely mathematical system, whereas Hegel intended to develop a social theory grounded in lived experience and historical movement.

We need a new visual structure to represent what Blunden described below:

At first something is put forward, is posited, presents itself. It presents itself also by way of negating something else, its negation, that which it is not. That which it is not may be what it was, it's form as opposed to its content, a pre-conception of it, or merely its negative pole - the "anti-thesis". This "other side" is essentially connected with the thesis, the thesis already contains implicitly the antithesis, as an inner contradiction within itself. A new and higher concept arises on the basis of conceiving both the thesis and antithesis in this way as identical with each other. Thus a new thesis is posited, .... and so on.

To achieve this goal, the Dialectic Room uses an ecological metaphor to conceptualize a structural tension, represented by the two windows, as a pair of Opposite Themes. Theme 1 functions as the Thesis and Theme 2 as the Antithesis. Achieving the “Fit” between them, symbolized by the door leading outdoors, involves identifying a Synthesis.

This approach makes the dynamic interplay between conceptual understanding and practical application more explicit, bridging the gap that the conventional diagram leaves unaddressed.

Since Themes are considered as Concepts, they can be interpreted using Hegel’s theory of concept, which consists of three moments: Individual, Particular, and Universal. Inspired by this idea, each pair of Opposite Themes can be reflected across these three sub-levels, showing their internal structure. At the same time, a set of Opposite Themes can be arranged across the three levels, forming a broader conceptual landscape.

The diagram below illustrates an example of arranging three pairs of Opposite Themes in three levels. For further details, see The Dialectic Room: A Meta-diagram for Innovation.

Crucially, the Dialectic Room methodology ensures that the process leads to tangible, practical change.

The diagram’s Door represents Orientation, symbolizing the direction of an actual action leading out of the interior space. This shift, from recognizing themes via the windows to executing action through the door, transforms the abstract Hegelian process into a concrete action method.

The philosophical core asserts that a concept not only represents its object but also, through the activity it mobilizes, constitutes and produces the object. Thus, the goal is to realize a “real concept” that brings about tangible change in social practice.

For example, in The Dialectic Room: A Meta-diagram for Innovation, I introduced my action after reflecting on three pairs of Opposite Themes. See the diagram below.

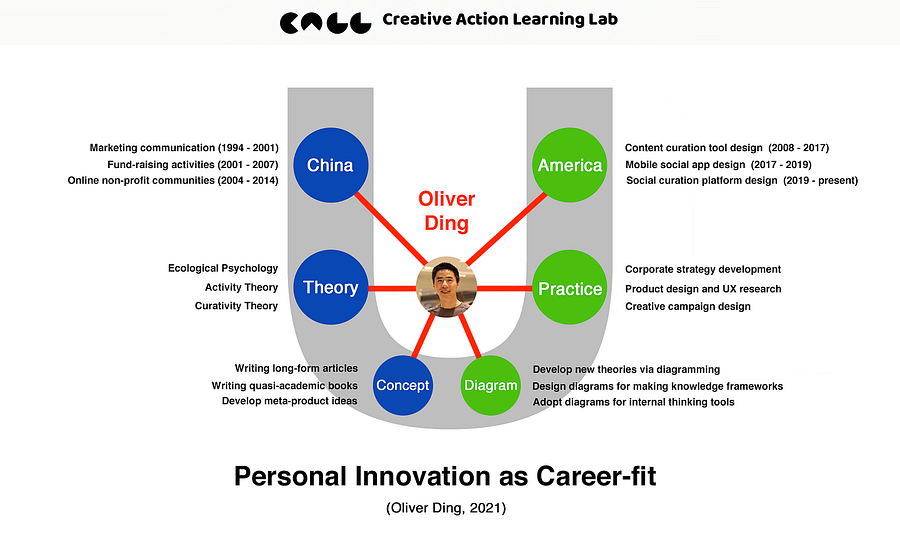

Inspired by the“ Individual - Particular - Universal" schema, I conducted a case study of my own career-fit by selecting three pairs of opposite themes from my past twenty years of work experience:

- Universal: China vs. America

- Particular: Theory vs. Practice

- Individual: Concept vs. Diagram

The first pair, “China vs. America,” reflects cross-cultural work and life experiences, highlighting significant differences between the two countries. The second pair, “Theory vs. Practice,” reflects cross-disciplinary knowledge and experience, emphasizing the gap between academic knowledge and practical work activities. The third pair, “Concept vs. Diagram,” reflects cross-domain cognitive experience. According to cognitive scientist Barbara Tversky, concepts involve linguistic thought, whereas diagrams involve spatial thought.

My strategy focused primarily on the Particular and Individual levels. From 2019 to 2021, the Theory-Practice fit and the Concept-Diagram fit became my main focus.

This case demonstrates how reflecting on Opposite Themes across multiple levels can guide practical decision-making and action, bringing Hegelian conceptual analysis into real-world application.

3. The Diagrammatic Innovation: The Thematic Space Metaphor

The Dialectic Room meta-diagram is a specific and original application of Thematic Space Theory, translating philosophical concepts into thematic spaces using an ecological metaphor.

A Thematic Space refers to a cognitive container where a person’s ideas, activities, and practices revolve around a particular theme. A theme can range from an established theory (e.g., “Activity Theory”) to a general concept (e.g., “Platform” or “Life”), or somewhere in between (e.g., “Design Thinking” or “UX”).

A tough situation with structural tension can be understood as a thematic space containing a pair of Opposite Themes. To visualize this special type of thematic space, the Dialectic Room employs an ecological metaphor approach.

Here, the term ecological metaphor does not refer to a conceptual metaphor in the sense used in cognitive linguistics. Instead, it describes a structural and spatial analogy that models thinking or activity through ecological relationships. In other words, it is not about mapping concepts from one domain to another, but about representing a systemic logic that connects parts and wholes, inside and outside, tension and transformation.

We can consider a tough situation with structural tension as a room with two windows and one door.

- a tough situation = a room

- a structural tension = a pair of Opposite Themes = two windows

- a final action = a door

A room is a container that separates the inside space from the outside space. There are several kinds of actions people can perform within a room. Here, I focus on a particular type of action: connecting the inside space to the outside space. Let’s call this action “Process.”

The two windows serve as interfaces that represent two “Tendencies.” Window 1 refers to Tendency 1, while Window 2 refers to Tendency 2. Each window provides its own view of the outside space.

Finally, there is a door that allows people actually to leave the room. The door refers to “Orientation,” which represents the direction of a real action — an act of moving from the inside space to the outside space.

Once you step into the outside space, you can treat it as a new room and repeat the same diagram.

This expresses a special kind of spatial logic. Terms such as “Process,” “Tendency,” and “Orientation” are textual placeholders for describing this logic. From the perspective of my diagram theory, a pure meta-diagram does not require text. For instance, the Yin-Yang symbol, or Taijitu, is a meta-diagram — can you find any text within it? However, we can add textual placeholders to a pure meta-diagram in order to make its structure easier to describe.

In this way, Thematic Space Theory provides a framework in which the meaning of the meta-diagram emerges from its intrinsic spatial logic, serving as a concrete and repeatable tool for thematic analysis. Building on this meta-diagram, additional theoretical resources can be curated to construct concrete analytical frameworks.

v1 - October 30, 2025 - 2,025 words