The Geometry of the Activity System Model

Point, Line, and Plane

by Oliver Ding

In this article, I present real-world examples of applying the Activity System Model using the Creative Diagramming method.

In 1987, Yrjö Engeström published his seminal work Learning by Expanding (1987/2014), in which he introduced the now-famous Activity System triangle, the concept and model of Expansive Learning, and the early formulation of the Developmental Work Research methodology. Since then, his research has greatly deepened our understanding of development and learning across diverse work settings and made major contributions to Cultural-Historical Activity Theory.

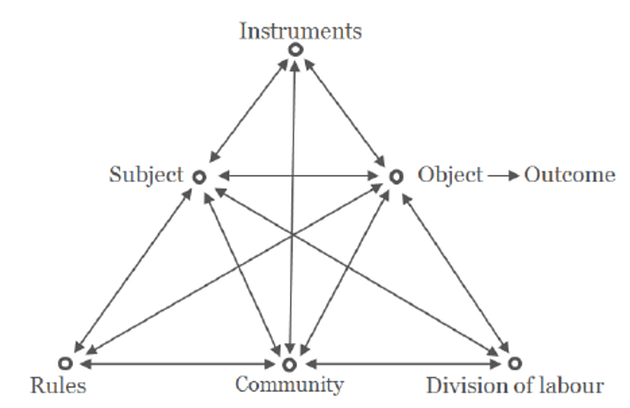

One of the major outcomes of Learning by Expanding is a diagram that aims to picture Leontiev’s activity system. Now the diagram has a nickname called “Engeström’s Triangle”.

The Engeström’s Triangle builds on the cultural-historical psychologists’ notion of mediation, represented in the upper part of the diagram as the triad of subject–instrument–object describing individual action. Engeström (1987) considered “a human activity system always contains the subsystems of production, distribution, exchange, and consumption.” (p.67). To account for these collective aspects, he expanded the original triangle by adding the lower layer, which includes community, rules, and division of labor.

Some authors regard this diagram as a graphical heuristic. For example, Geri Gay and Helene Hembrooke (2004) wrote, “…Building on these principles, Alexei N. Leont’ev (1981) created a formal structure for operationalizing the activity system as a complex, multilayered unit of analysis (figure 1.1). His model is less a representation of reality than a heuristic aid for identifying and exploring the multiple contextual factors that shape or mediate any goal-directed, tool-mediated human activity.” (p.2).

Similarly, Clay Spinuzzi (2020) described Engeström’s model as a graphic heuristic, “…Engeström provided a graphical heuristic (the now-famous triangle) for picturing Leontiev’s activity system. This heuristic, which has been derided by some critics (e.g., Miller, 2011)…”.

However, Spinuzzi also emphasized the model’s practical and communicative value, “This heuristic…was meant not only as an analytical device for researchers but (critically) also as a way to communicate with — and codesign work with — research participants (e.g., Engeström, 1999; Engeström & Sannino 2010). That is, it served as an interventionist ‘language game’ (Ehn 1989) similar to the prototypes and organizational games that Bødker and other participatory designers used to leverage the tacit expertise of participants. This point has been overlooked by those who have critiqued the triangle heuristic as an oversimplified theoretical tool.”

For a more detailed discussion, see Method 101: Diagramming as Theorizing.

Using the Activity System Model

How do we use the Activity System Model?

There are many ways to use a knowledge framework. Some researchers and scholars employ it to guide formal research projects.

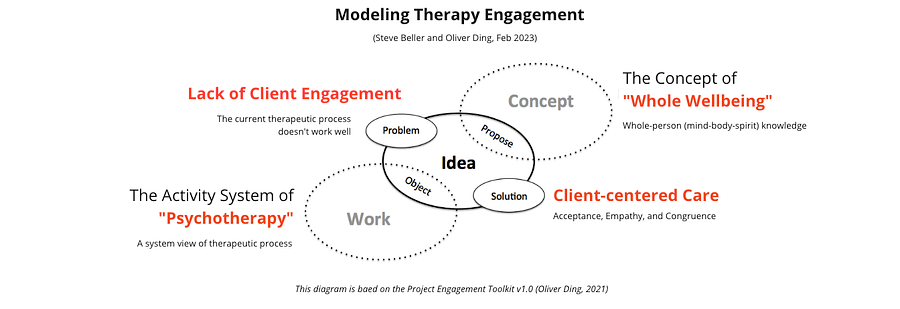

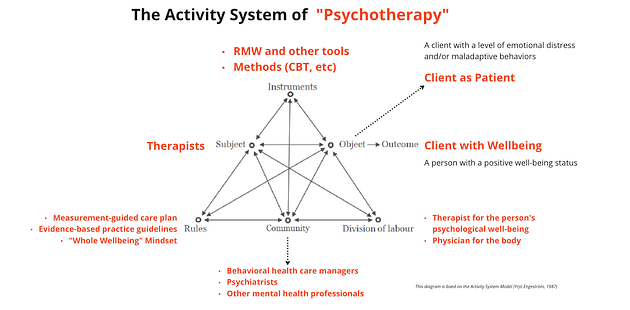

I tend to use it as a heuristic tool in strategic design projects. In 2023, I worked on a project about psychotherapy and applied the Activity System Model along with several related frameworks.

I began with the basic model of the Project Engagement toolkit (v1.0).

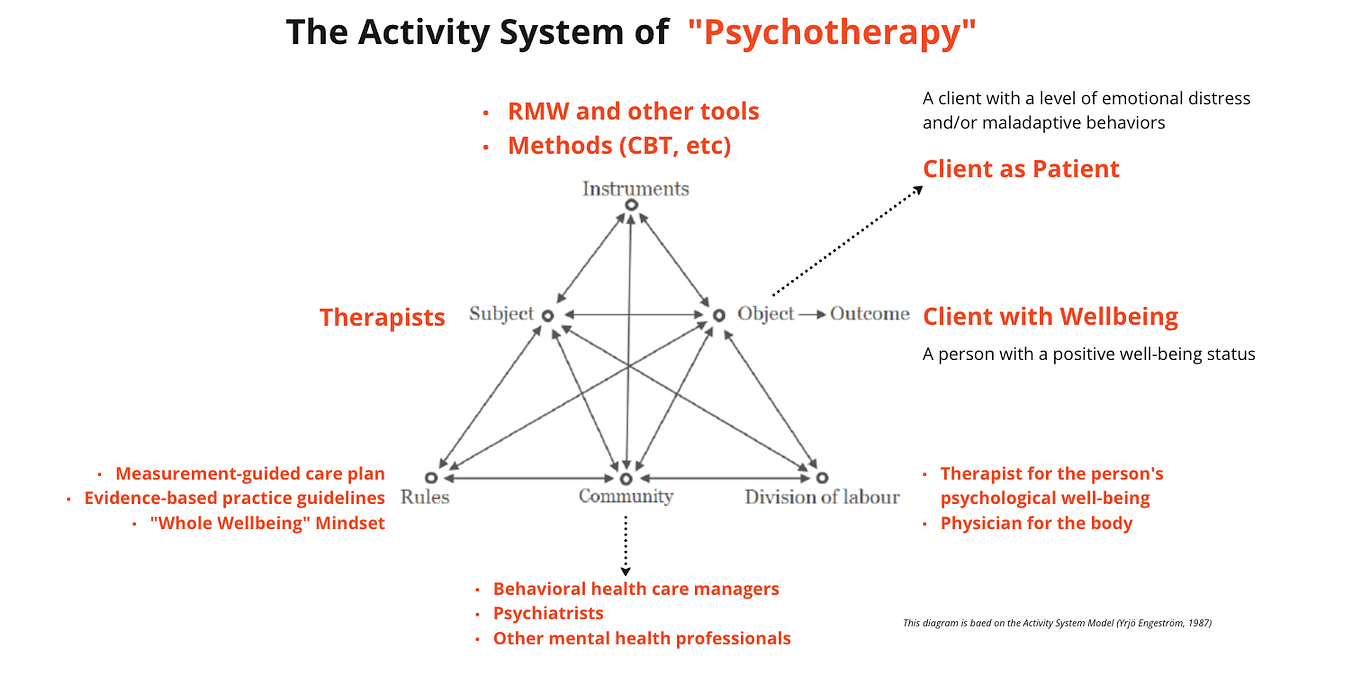

Then I moved on to construct the Activity System of Psychotherapy.

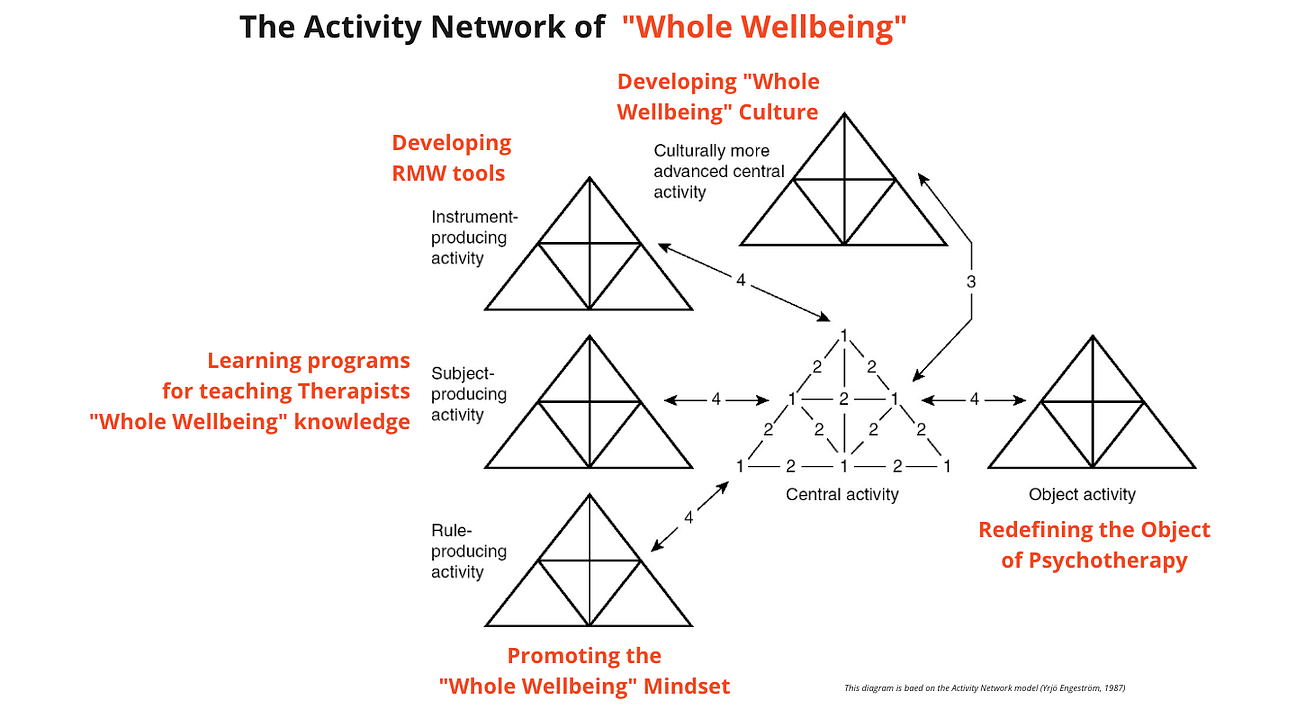

I also applied the Activity Network Model to the same project (see the diagram below).

Together, these three diagrams provided a systematic framework for understanding the complexity of the client’s “Whole Wellbeing” project. I used them to curate concrete materials and facilitate strategic discussions.

Expanding the Activity System Model

Over the past several years, I have applied the Activity System Model to numerous knowledge projects. During this process, I encountered a recurring challenge: the ideal form of the diagram does not leave sufficient creative space for emerging theoretical concepts or situational themes.

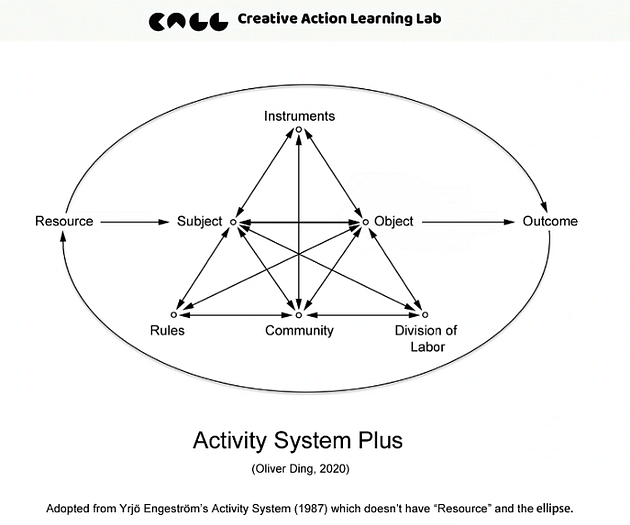

For example, the Activity System Model does not include the concepts of Environment or Resource. To address this limitation, I created an expanded version called “Activity System Plus”, which incorporates the concept of Resource.

I also added an ellipse connecting “Outcome” and “Resource.” This connection represents the notion of “Reproduction of Activity,” meaning that the outcome of one activity can become a resource for another.

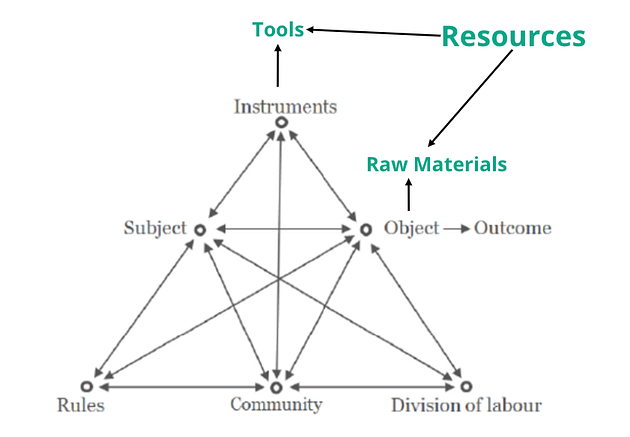

The concept of Resource was also inspired by a diagram from TRIZ, which I discovered in Kalevi Rantanen and Ellen Domb’s 2007 book Simplified TRIZ: New Problem Solving Applications for Engineers and Manufacturing Professionals.

The book includes a chapter titled Mapping Invisible Resources, which explores this topic in depth.

Every diagram can display only a limited number of concepts. Knowledge creators must therefore distinguish between primary and secondary concepts.

In the Activity System Model, “Mediation” is a primary concept, while “Resources” and “Environments” are secondary concepts. If your research focuses on Resources or Environments, you can interpret them as aspects of Mediation. Certain types of Resources may also be understood as “Raw Materials,” which form part of the Object.

However, if you wish to treat Resources and Environments as primary concepts in a knowledge framework, you will need to explore alternative models or design one of your own.

In 2019, I developed a framework called Life Curation, which includes a module named “Resources — Results Analysis.” The framework suggests that individuals can construct their own creative containers to curate resources into meaningful results.

Later, I used the concept of “Resource” in the Lifesystem framework, developed within the Ecological Practice approach, which emphasizes the ecological meaning of objects and environments. This perspective has proven highly useful for rethinking Resources and Opportunities.

Mindset and Activity

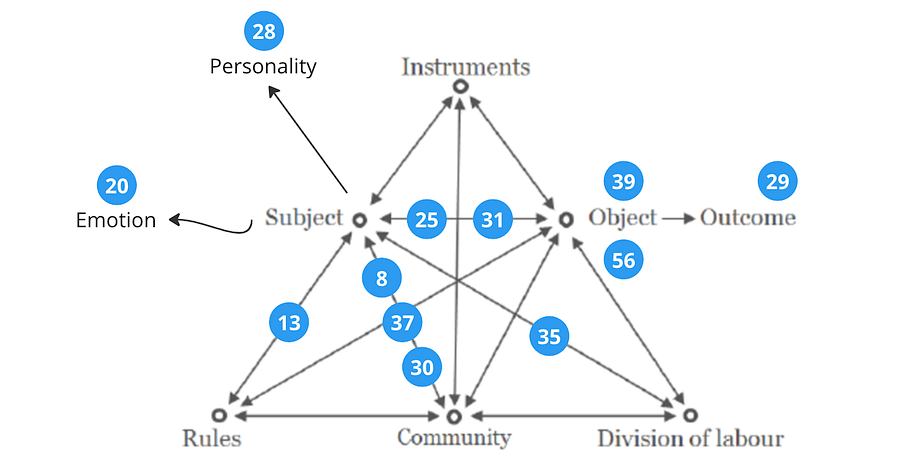

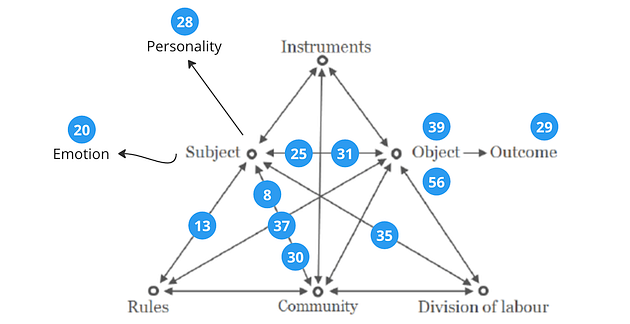

In 2023, I worked on a project focused on mindsets, in which I applied the Activity System Model in a creative way.

My client was developing a typology of mindsets, and I used the Activity System Model to test and organize this typology.

The numbers on the diagram above correspond to the different types of mindsets identified in the client’s work. By mapping these types onto the Activity System Model, we can visualize the relationships between them, effectively transforming a typology into a systematic framework.

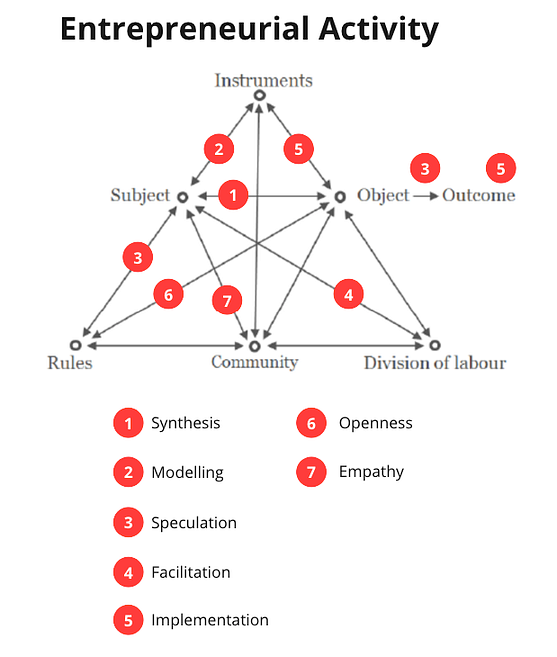

I also applied the Activity System Model to analyze Entrepreneurial Activity and its associated mindsets (see the diagram below).

What can we learn from these examples?

The Activity System Model is a powerful tool for understanding abstract concepts and creative themes systematically, as it provides a meaningful contextual framework that connects concepts, actions, and outcomes.

The Activity System Model +

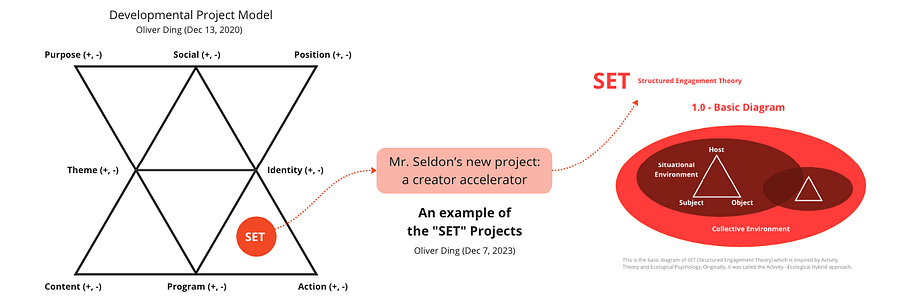

From October to December 2023, I focused on identifying potential thematic spaces of the Developmental Project Model (DPM).

I used three themes to define a potential thematic space and applied a related knowledge framework to better understand it. The diagram below exemplifies this approach: The “Identity — Program — Action” Thematic Space and the “SET” Projects.

Eventually, I developed “Developmental Project Model +” (DPM+), a diagram network and toolkit.

If one diagram is not enough, we can use a diagram network!

In this way, we have a “1+N” model for understanding the concept of Developmental Projects.

- The “1” represents the concept of Developmental Projects and the base model of the DPM — an independent theoretical concept and knowledge model.

- The “N” represents various theoretical approaches and knowledge frameworks.

For simplicity, we denote the “1” as DPM (Developmental Project Model) and the “N” as a set of knowledge frameworks. The following examples illustrate this approach.

- DPM+Activity Theory

- DPM+Attachance Theory

- DPM+Knowledge Center

- DPM+ECHO (The ECHO Way)

- DPM+Value Circle

- DPM+AAS (Anticipatory Activity System)

- DPM+PDF (Persona Dynamics Framework)

- DPM+CLC (Creative Life Curation)

This is a fantastic model!

This is a new model for building knowledge frameworks!

The outcome is amazing. I edited a possible book titled Mapping Developmental Projects: Life, Stories, and Thematic Spaces.

Later, I applied the same method to the Meaning Discovery Canvas and the Life Discovery Canvas.

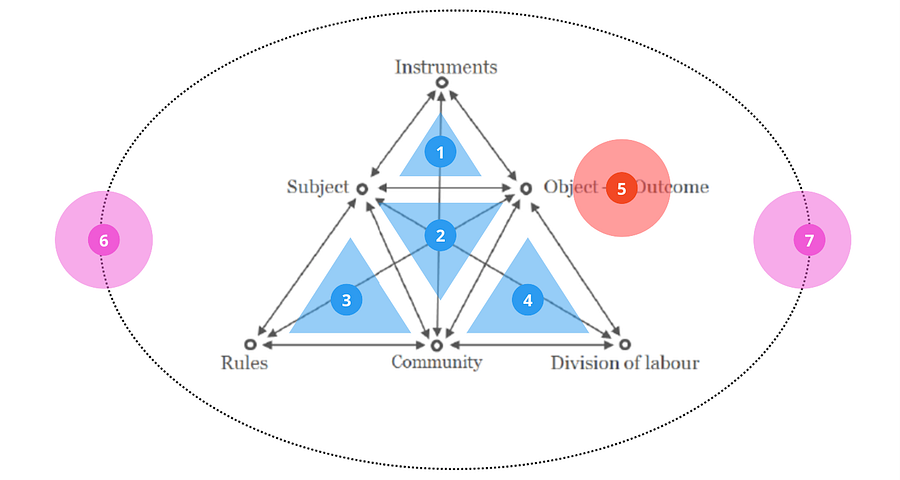

We can now extend this method to the Activity System Model (see the diagram below).

I discovered 7 potential thematic spaces in the above diagram.

#1 The “Subject — Instruments — Object” Thematic Space

#2 The “Subject — Community — Object” Thematic Space

#3 The “Subject — Rules — Community” Thematic Space

#4 The “Community — Object — Division of Labour” Thematic Space

#5 The “Object — Outcome” Thematic Space

#6 The “Resource” Thematic Space

#7 The “Reward” Thematic Space

Some of these thematic spaces were implicitly recognized by Engeström, though he did not explicitly use the term “Thematic Space.”

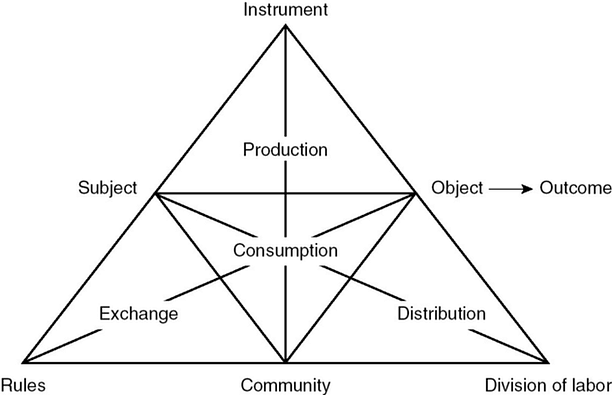

The diagram above appeared in Engeström’s 1987 book. Engeström noted that Karl Marx provided an essential analysis in the introduction to Grundrisse, “Production creates the objects which correspond to the given needs; distribution divides them up according to social laws; exchange further parcels out the already divided shares in accord with individual needs; and finally, in consumption, the product steps outside this social movement and becomes a direct object and servant of individual need, and satisfies it in being consumed. Thus production appears to be the point of departure, consumption as the conclusion, distribution and exchange as the middle (…).” (Marx 1973, 89. cited in Engeström, 1987, p.94)

These aspects of human activity correspond to the sub-systems of the Activity System Model. We can use them to define four thematic spaces:

#1 = Production

#2 = Consumption

#3 = Exchange

#4 = Distribution

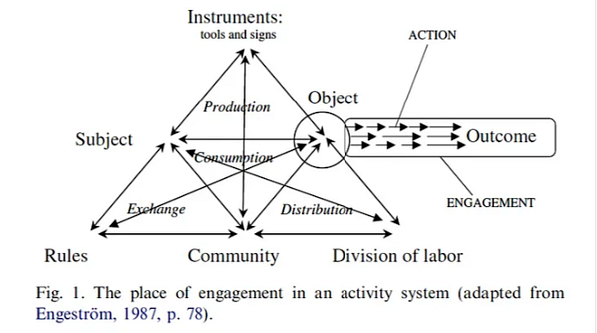

In 2008, Engeström published a short paper responding to Gonzalez’s suggestion of adding a new level to Activity Theory. He agreed that it is useful and necessary to identify an intermediate unit between collective activity and individual action. However, he pointed out that Gonzalez’s notion of working sphere (engagement) does not align with the theoretical tradition of Activity Theory, as it adopts a subjectivist perspective. Engeström explained, “Activities are oriented to and driven by objects and motives. Actions are oriented to and driven by goals…recurring working spheres/engagements…are also outcomes…they are historically built into the object, division of labor and rules of the work activity.” He placed the work spheres/engagement between object and outcome (see the left part of the diagram above).

The above diagram is not a normal form of Engeström’s Triangle. However, this example demonstrates the power of a simple triangle and its flexibility in servicing theoretical discussion. It also reminds us that the “object-outcome” part is a critical component of the activity system model.

The term “work spheres/engagement” was suggested by Gonzalez. In my framework, I use “Development” as the primary theme of this thematic space:

#5 = Development = The “Object — Outcome” Thematic Space

The remaining thematic spaces (#6 and #7) are inspired by my Activity System + (2020 version).

Thus, we now have seven thematic spaces and their corresponding concepts:

#1 = Production

#2 = Consumption

#3 = Exchange

#4 = Distribution

#5 = Development

#6 = Resource

#7 = Reward

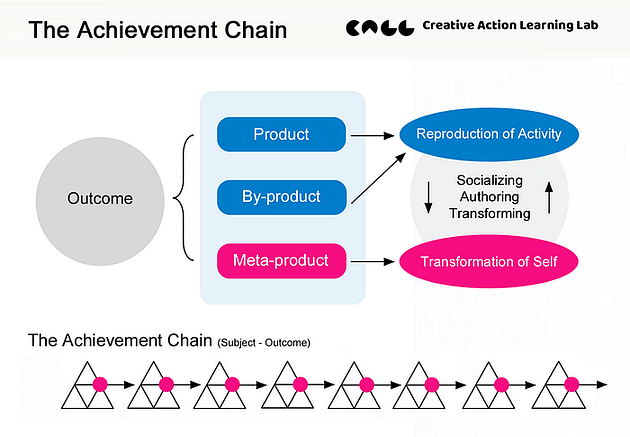

To further develop the Activity System Model +, we can incorporate relevant knowledge frameworks to better understand the identified thematic spaces. For example, the Achievement Chain (see the diagram below) can be used to analyze #5: Development (Object–Outcome Thematic Space).

The Achievement Chain draws inspiration from several theoretical sources:

- The Activity System Model (Yrjö Engeström,1987): Subject — Outcome.

- The evolving systems approach to the study of creative work (Howard E. Gruber, 1974,1989): By-product.

- The constructive — developmental approach (Robert Kegan, 1982, 2009): The Evolving Self.

For more details, see Life-to-be-Owned: The Achievement Chain.

The 1+N Approach

The previous section applied the 1+N approach to the Activity System Model.

Is this an innovative method for using knowledge frameworks and diagrams?

To examine this, we can compare Activity System Model + with the Activity-Oriented Design Method (AODM).

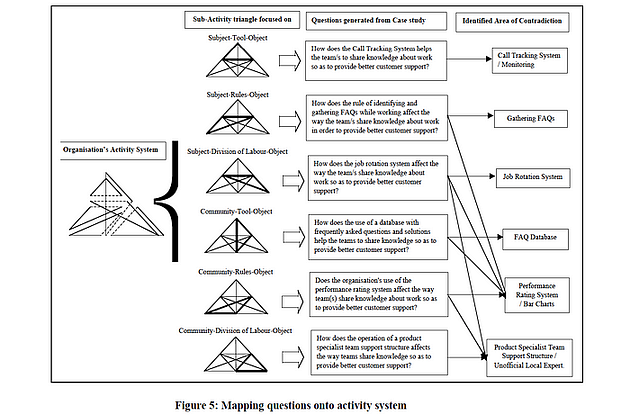

Noting the lack of a standardized method for applying Activity Theory within HCI, Mwanza (2001) developed an Activity-Oriented Design Method (AODM), which includes four methodological tools. One of these tools, Activity Notation, breaks down the overall activity system of a situation into smaller, manageable sub-activity triangles (see the diagram below).

She also developed a set of general research questions specific to each combination within the activity notation. Mwanza explained, “These questions are used as pointers to what to look for during observational studies, also in questionnaires and interviews as triggers to help decide on what questions to ask.” Finally, researchers and designers can analyze and interpret collected data using a key concept of Activity Theory: contradictions.

Mwanza identified several sub-triangles, though she did not explicitly use the term “Thematic Space.” In contrast, the Activity System Model + allows each concept, sub-triangle, and other structures to be mapped to thematic spaces, for example:

- Each concept represents a thematic space.

- Each sub-triangle represents a thematic space.

- The Object–Outcome transformation represents a thematic space.

- The Resource–Reward container represents two thematic spaces.

Mwanza didn’t adopt other knowledge frameworks to explain these sub-triangles. In contrast, the Activity System Model + allows people to adopt other knowledge frameworks to explain thematic spaces and make a situational toolkit.

In this way, the 1+N approach provides a flexible way for people to use a theoretical knowledge framework.

Point, Line, and Plane

In the above discussion, we identified three types of creative diagramming using the Activity System Model:

- Point: Each concept corresponds to a point.

- Line: Each connection between two concepts corresponds to a line.

- Plane: Each thematic space corresponds to a plane.

In the Activity System of “Psychotherapy”, only points were represented, because only the concepts themselves were used.

The diagram below differs: I placed numbers on lines to highlight relationships between concepts.

Finally, I mapped the thematic spaces of the model, with each thematic space forming a plane.

This illustrates the geometry of the Activity System Model, showing a creative diagramming method for exploring the potential of any knowledge frameworks and diagrams.

As Engeström himself noted, “I use the graphic models in series of successive variations, not just as singular representations…With the help of such variations, I try to demonstrate how the models can depict movement and change. The reader is invited to formulate and test his own variations.” (1987, p.47)

Thus, we should remember that the diagram is not a dogma but a guide to action.

Note:

This article was originally featured in my 2024 book draft: Creative Diagramming: The Fifth Way of Knowing and Early Discovery.

v1.0 - October 29, 2025 - 2,356 words