Toward a Project-Oriented Ecology of Adult Development

Vygotsky’s “Ecological Mind” and a New Approach to Adult Development

by Oliver Ding

This article is part of a possible book, Developmental Projects: The Project Engagement Approach to Adult Development.

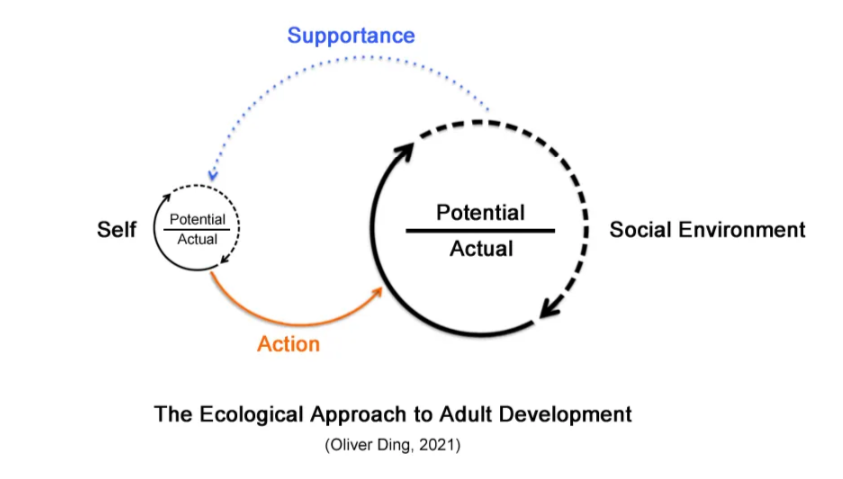

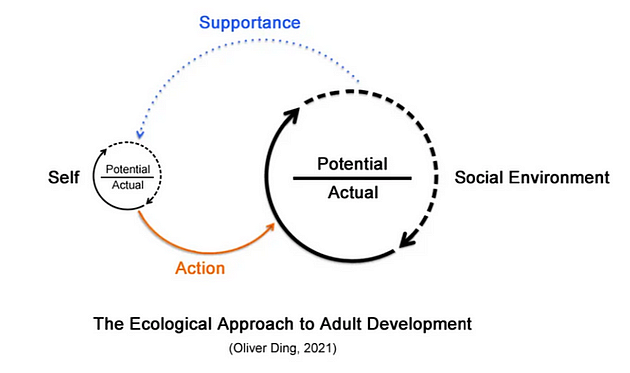

This diagram shows an ecological model of adult development. The Self and the Social Environment each contain Potential and Actual states. Development unfolds through a reciprocal loop: Action (from Self to Environment) and Supportance (from Environment to Self). In short, people realize potentials by acting in the world, and the world, in turn, supports and transforms that development.

It was inspired by Lev Vygotsky’s later ideas regarding development and environment, especially the ZPD model (Zone of Proximal Development). I first developed it for the Platform for Development project in 2021. It was introduced in the book draft, Platform for Development: The Ecology of Adult Development in the 21st Century.

At that time, my primary goal was to introduce the concepts of “Supportance” and “Developmental Platform” for the Platform Ecology project, an application designed to test the Ecological Practice Approach.

This article reviews the original ideas of this new approach to adult development and places the concept of “Developmental Projects” within this context. Developmental Projects provide structured opportunities for personal growth, enabling individuals to engage meaningfully with their environments. Building on these projects, Developmental Platforms highlight social formations that strongly support adult development, serving as intermediate frameworks that bridge theory and practice.

A central perspective in this approach is viewing Projects and Platforms as successive stages within a broader Enterprise. A Project may grow into a Platform, which in turn enables new Projects to emerge. From this standpoint, social groups such as Organizations, Communities, Theory Schools, and Technological Platforms can be understood as outcomes of Developmental Projects, reflecting accumulated patterns of human action and the supportive structures that foster continued development.

Contents

Part 1: The Environment of Adult Development

1.1 Levinson’s Life Structure

1.2 Ryan & Deci: Self-Determination Theory

1.3 Ryan & Deci: Embedded Social Context

1.4 Vygotsky: Zone of Proximal Development

1.5 Bronfenbrenner: Bioecological Systems Theory

Part 2: The Ecological Practice Approach to Development

2.1The Ecology of Human Development

2.2 Self, Other, and Supportance

2.3 Potential, Actual, and Development

Part 3: Developmental Projects and Beyond

3.1 The Concept of Developmental Project

3.2 The Concept of Developmental Platform

3.3 Project, Platform, and Development

3.4 Activity, Enterprise, and Development

3.5 The Development of Social Environment

Conclusion: Toward a Project-Oriented Ecology of Adult Development

Part 1: The Environment of Adult Development

Developmental psychology is a major branch of psychology, with many established theories of adult development. My goal is not to propose a brand-new theory but rather to explore the relationship between environments and individuals from the perspective of adult development.

Adult developmental theorists and psychologists have long considered the role of environments in development. Instead of conducting a systematic literature review, I will highlight a selection of relevant theories to guide our discussion.

1.1 Levinson’s Life Structure

Renowned adult developmental theorist Daniel J. Levinson identified six major issues that must be addressed by any structural approach to adult development in his 1986 article, A Conception of Adult Development.

Levinson is best known for his stage-crisis view and age-graded model of development. Based on studies of both men and women, Levinson and his colleagues proposed that individuals progress through an orderly sequence of stable and transitional periods, which align with chronological age.

To develop his theory of adult development, Levinson introduced key concepts such as Life Course, Life Cycle, and Individual Life Structure. According to Levinson:

- “Life course…refers to the concrete character of a life in its evolution from beginning to end…the word course indicates sequence, temporal flow, the need to study a life as it unfolds, over the years. To study the course of a life, one must take account of stability and change, continuity and discontinuity, orderly progression as well as stasis and chaotic fluctuation.”

- “The imagery of ‘cycle’ suggests that there is an underlying order in the human life course…The course of a life is not a simple, continuous process. There are qualitatively different phases or seasons. The metaphor of seasons appears in many contexts. There are seasons in the year. Spring is a time of blossoming, and poets allude to youth as the springtime of the life cycle. Summer is the season of greatest passion and ripeness. An elderly ruler is ‘the lion in winter.’…There is now very little theory, research, or cultural wisdom about adulthood as a season (or seasons) of the life cycle.”

- “The key concept to emerge from my research is the life structure: the underlying pattern or design of a person’s life at a given time. It is the pillar of my conception of adult development. A theory of life structure is a way of conceptualizing answers to a different question: ‘What is my life like now?’…in pondering these questions, we begin to identify those aspects of the external world that have the greatest significance to us…The primary components of a life structure are the person’s relationships with various others in the external world.”

Levinson employs a nested structure of time to develop his theory of adult development: Life Course [Life Cycle (Life Structure)].

This framework connects three different levels of analysis:

- Macro level — Life Course

- Meso level — Life Cycle

- Micro level — Life Structure

An interesting aspect of Life Structure is its primary components. Levinson asserts that only one or two components — rarely as many as three — occupy a central place in an individual’s life structure. He explains, “Most often, marriage — family and occupation are the central components of a person’s life, although wide variations occur in their relative weight and in the importance of other components. The central components are those that have the greatest significance for the self and the evolving life course. They receive the largest share of the individual’s time and energy, and they strongly influence the character of the other components. The peripheral components are easier to change or detach; they involve less investment of self and can be modified with less effect on the fabric of the person’s life.”

Levinson’s discovery aligns with common sense: the two primary components of life structure are home (marriage and family) and work (occupation). Levinson also identifies six key issues of adult development from a structural perspective:

- What are the alternative ways of defining a structural stage or period?

- How should we balance the emphasis on structure-building periods (stages) versus structure-changing (transitional) periods?

- How can we effectively distinguish between hierarchical levels and seasons of development?

- Are there age-linked developmental periods in adulthood?

- What are the relative merits and limitations of various research methods?

- How can we integrate the developmental perspective with the socialization perspective?

Issue #6 highlights the need for an interdisciplinary approach to developmental studies, particularly in bridging psychological research and sociocultural research. According to Levinson, “By and large, psychologists study the development of properties of the person — cognition, morality, ego, attitudes, interests, or psychodynamics…Indeed, a developmental perspective in psychology has traditionally meant the search for a maturationally built-in, epigenetic, preprogrammed sequence.” On the other hand, “The social sciences…look primarily to the sociocultural world for the sources of order in the life course. They show how culturally defined age grades, institutional timetables, and systems of acculturation and socialization shape the sequence of our lives. What we may broadly term the socialization perspective … holds that the timing of life events and the evolution of adult careers in occupation, family, and other institutions is determined chiefly by force in the external world; forces in the individual biology or psyche produce minor variance around the externally determined norms.”

Here, we observe a clear theoretical conflict between two fields: development vs. socialization. Levinson advocates for a balanced approach to understanding the order of the life course. He states, “What about the evolution of the life structure? Is it determined primarily from within or from without? Is it a product more of development or of socialization? As I have already indicated, the life structure constitutes a boundary — a mediating zone between personality structure and social structure. It contains aspects of both and governs the transactions between them. The life structure is a pattern of relationships between the self and the world. It has an inner-psychological aspect and an external — social aspect. The universal sequence of periods in the evolution of the life structure has its origins in the psycho-biological properties of the human species, as well as in the general nature of human society at this phase of its evolution (Levinson, 1978, Ch. 20)”.

The Development vs. Socialization issue reflects similar debates across various fields. In Activity Theory, this tension is expressed as Externalization vs. Internalization and Individual Actions vs. Collective Activities. In general, it appears as the connection between individual life development and social life development.

These parallels highlight the broader challenge of integrating personal growth with social structures and cultural processes in developmental studies.

1.2 Ryan & Deci: Self-Determination Theory

Now, let’s turn to a general psychological theory of human behavior and personality development: Self-Determination Theory (SDT).

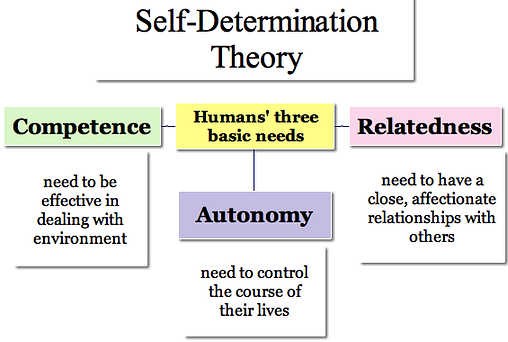

There are many established theories of motivation, but SDT is particularly relevant to our discussion because it focuses on how social-contextual factors either support or hinder human thriving. It emphasizes the satisfaction of three basic psychological needs: Competence, Relatedness, and Autonomy.

SDT is an empirical and humanistic psychological theory. As an empirical approach, it relies on operational definitions, observational methods, and statistical inferences to build its framework. As a humanistic approach, it rejects the behaviorist perspective, emphasizing intrinsic motivation and the active role of individuals in their own development.

According to Richard M. Ryan and Edward L. Deci, “…one can observe the human capacities to be apathetic and alienated, to disconnect from and dehumanize others, and to behave in ways that imply fragmentation and inner division rather than integration. These seemingly contradictory human natures, with capacities for activity and passivity, integrity and fragmentation, caring and cruelty, can be theoretically approached in different ways. As briefly mentioned, one approach, taken by the more behavioristic schools of thought, has assumed that organisms can be conditioned, programmed, or trained to be more ‘positive’ in functioning, or they can be programmed, conditioned, or trained to be more ‘negative.’ In other words, the contradiction is resolved within such theories by assuming a relatively empty or highly plastic organism that is shaped to be either more positive or more negative, with little need to consider the constraints or contents of human nature.” (2017, p.9)

In recent years, there has been a growing discussion about behavior design and the science of persuasion in the context of digital platform development. One notable example is the 2016 article The Scientists Who Make Apps Addictive, published in The Economist’s 1843 magazine.

The article opens by introducing B.F. Skinner and the Skinner Box, “In 1930, a psychologist at Harvard University called B.F. Skinner made a box and placed a hungry rat inside it. The box had a lever on one side. As the rat moved about it would accidentally knock the lever and, when it did so, a food pellet would drop into the box. After a rat had been put in the box a few times, it learned to go straight to the lever and press it: the reward reinforced the behaviour. Skinner proposed that the same principle applied to any ‘operant’, rat or man. He called his device the ‘operant conditioning chamber’. It became known as the Skinner box. Skinner was the most prominent exponent of a school of psychology called behaviourism, the premise of which was that human behaviour is best understood as a function of incentives and rewards. Let’s not get distracted by the nebulous and impossible to observe stuff of thoughts and feelings, said the behaviourists, but focus simply on how the operant’s environment shapes what it does. Understand the box and you understand the behaviour. Design the right box and you can control behaviour.”

In a 2018 article titled The 21st Century Skinner Box, the author Ronald E. Robertson points out, “Unlike behavior scientists of the past, engineers and designers working at companies like Google, Amazon, Facebook, Microsoft, and Apple have enormous sample sizes to draw from, and the nature of digital environments allows them to rapidly adjust their experiments on the fly. The shape and color of the buttons you press, the timing of each notification you receive, and the content of every piece of information that reaches you have often been curated through this data-driven process of mass experimentation. And companies don’t just run these experiments once; they run them but over and over again, storing each stimulus and response, customizing reinforcers and schedules of reinforcement to maximize their influence. Over time, this enables companies to predict, shape, and condition each user’s habits and triggers on a scale previously unimaginable.”

Ryan and Deci consider SDT as an alternative to Behaviorism. They emphasize that the assumption behind SDT is a human nature “which is deeply designed to be active and social and which, when afford a ‘good enough’ (i.e., a basic-need-supportive) environment, will move toward thriving, wellness, and integrity. Yet some of the very features of this adaptive nature also make people vulnerable to being derailed or fragmented when environments are deficient in basic need supports. Social contexts can be basic need-thwarting, with various developmental costs, including certain defensive or compensatory strategies… According to SDT, therefore, our manifest human nature is, to a large degree, experience dependent — its forms of expression are contingent on the conditions of support versus thwarting and satisfaction versus frustration of these basic needs. SDT places human beings, with their active, integrative tendencies, in dialectical relation with ambient social contexts that can either support or thwart those tendencies.” (2017, p.9)

Unlike Behaviorism, the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) approach accepts both “bad” and “good” environments from a dialectical stance, recognizing that environments can either foster or hinder individual growth. Ryan and Deci define the “good” environment as one that supports the fulfillment of basic psychological needs. They characterize social environments in terms of three key dimensions, “We thus characterize social environments in terms of the extent to which they are: (1) autonomy supportive (versus demanding and controlling); (2) effectance supporting (versus overly challenging, inconsistent, or otherwise discouraging); and (3) relationally supportive (versus impersonal or rejecting). Autonomy support includes affordances of choice and encouragement of self-regulation, competence supports include provisions of structure and positive informational feedback, and relatedness supports include the caring involvement of others.” (2017, p.12)

It’s important to highlight that the basis of Self-Determination Theory (SDT) rests on a distinctive view of human needs. SDT theorists assert that there is a core set of psychological needs that are universally essential for optimal human functioning, regardless of developmental epoch or cultural setting. Ryan and Deci emphasize, “Within SDT, needs are specifically defined as nutrients that are essential for growth, integrity, and well-being… SDT’s three basic psychological needs are those for autonomy, competence, and relatedness” (Ryan & Deci, 2017, p.10).

Ryan and Deci also make a distinction between basic physiological needs and basic psychological needs. The former refers to the nutrients required for bodily health and safety, such as “oxygen, clean water, adequate nutrition, and freedom from physical harms” (Ryan & Deci, 2017, p.10). These physiological needs are essential for survival, but they differ from the psychological needs that SDT focuses on.

This distinction mirrors the material and sociocultural aspects of Platforms in my approach. In my previous article, The Supportive Cycle (v1.0), I explained, “From the perspective of the ecological practice approach, the concept of Affordance corresponds to the material aspect of Platform, while the concept of Supportance corresponds to the sociocultural aspect of Platform.” In GO Theory, platforms are considered a typical example of a social environment.

However, there is a key difference between SDT and my approach. While SDT focuses solely on basic psychological needs, I extend the Affordance — Supportance pair into a potential hierarchical loop, where these two aspects are dynamically interrelated and mutually supportive, creating a continuous cycle of development.

Ryan and Deci also consider the concept of Awareness as a foundational element of autonomous motivation and basic need satisfaction. They emphasize, “The concept of awareness is seen within SDT as a foundational element for proactively engaging one’s inner and outer worlds, and meeting demands and challenges. Awareness is crucial to eudaimonic living and can facilitate basic need satisfaction and wellness. The concept of awareness in SDT refers to open, relaxed, and interested attention to oneself and to the ambient social and physical environment. Such receptive attention has long been discussed within dynamic approaches to psychotherapy.”

The concept of Awareness serves as a bridge that connects Self-Determination Theory (SDT) with my own ideas, particularly the ecological practice approach and Developmental Platform. My approach is deeply influenced by James J. Gibson’s ecological psychology. The concept of Supportance in my work is inspired by Gibson’s theory of Affordance. Both Affordance and Supportance refer to potential action possibilities in the environment, yet they require individuals to raise awareness of both the ambient physical and social environments. According to Gibson, “Perceivers are not aware of the dimensions of physics. They are aware of the dimensions of the information in the flowing array of stimulation that are relevant to their lives” (Gibson, p.293). By perceiving the relevant information, people can perceive affordances and supportances from their environment.

After perceiving and recognizing affordances and supportances, individuals can decide whether they want to actualize these action possibilities and take concrete actions. This decision-making process is closely tied to Self-Determination Theory (SDT), particularly in the realm of motivation and basic psychological needs. When people perceive opportunities (whether physical or social) that align with their intrinsic needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, they are more likely to be motivated to engage with these possibilities.

1.3 Ryan & Deci: Embedded Social Context

According to Ryan and Deci, there are two types of social contexts:

- Proximal social contexts

- Pervasive social contexts

Ryan and Deci point out, “…we have focused primarily on the influences of proximal social contexts — for example, families, peer groups, schools, teams, and work organizations — on the individuals’ motivation, development, and wellness. We describe these contexts as ‘proximal’ in the sense that the individuals have direct interpersonal contacts with the people who make up these contexts. As SDT evidence has shown, proximal social contexts have a powerful impact on motivation, behavior, and experience, effects that are strongly mediated by basic psychological need satisfactions and frustrations.” (2017, p.561)

Pervasive social contexts refer to abstract social-cultural systems. According to Ryan and Deci, “Yet proximal social contexts are themselves embedded within broader or more encompassing social systems, both formal and informal, which influence need satisfaction and behavior in myriad ways. These pervasive contexts include the overarching cultural and religious identifications, political structures, and economic systems within which proximal social contexts are constructed and occur (Ryan & Deci, 2011).” (2017, p.562)

Examples of proximal social contexts include families, peer groups, schools, teams, and work organizations. These are traditional social contexts. However, their approach has several limitations when applied to more complex, dynamic, and developmental environments such as projects.

Ryan and Deci treat proximal and pervasive social contexts as largely separate categories. However, in reality, social contexts exist on a continuum rather than as two fixed layers. Their framework does not fully account for how social contexts evolve over time. For example, a proximal context (e.g., a startup team) can transform into a pervasive context (e.g., an industry-wide movement) through growth and institutionalization. SDT primarily describes how individuals respond to existing social contexts but does not sufficiently explore how people actively shape and create new contexts. Social actors do not merely navigate static proximal or pervasive contexts — they construct new social environments through activities like initiating projects, forming movements, and institutionalizing ideas.

Instead of treating social contexts as pre-existing structures, I propose viewing them through the lens of projects, drawing from Project-oriented Activity Theory. I have identified two types of projects:

- Abstract projects, which function as social movements at a broad level.

- Concrete projects, which represent regular work projects at a specific level.

In this framework, abstract projects correspond to pervasive social contexts, while concrete projects align with proximal social contexts. It is important to note that pervasive social contexts do not always influence behavior indirectly. As Ryan and Deci emphasize: “Pervasive contexts can at times directly affect people’s behaviors and need satisfactions by actively regulating or even blocking their activities… cultural or religious authorities can prohibit or even punish certain lifestyle choices” (Ryan & Deci, 2017, p. 562).

From the perspective of Project-oriented Activity Theory, there is a concept behind a project. The formulation of a concept has three phases: Initialization, Objectification, and Institutionalization. At the institutionalization phase, a project evolves into a social movement. Given that cultural authorities often play a role in this institutionalization process, a project-turned-social-movement can indeed be understood as a pervasive social context.

However, during the Initialization and Objectification phases, a project primarily exists as a series of concrete projects, which function as proximal social contexts. As Ryan and Deci explain: “Yet the primary influence of these distal contexts is typically more indirect, as pervasive cultural norms or economic structures present ‘invisible’ or implicit values, constraints, and affordances, which are then reflected in more proximal social conditions and conveyed by socializing agents from parents and teachers to cultural messengers such as religious leaders, politicians, and celebrities” (Ryan & Deci, 2017, p. 562).

By understanding social contexts through projects, we move away from the static view of social environments in SDT and toward a more process-oriented, agent-driven model.

1.4 Lev Vygotsky’s “Ecological Mind”

Vygotskian scholars do not use the term Ecological Mind to describe Vygotsky’s ideas. I use it here to highlight three of his concepts that are highly relevant to ecological approaches in psychology: the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), Perezhivanie, and the Social Situation of Development. These three ideas are crucial for understanding Vygotsky’s thoughts on social context and environment, and it is best to consider them as an interconnected whole.

According to Andy Blunden, “Perezhivanie is a Russian word, usually translated as ‘a lived experience.’ and used in connection with ‘social situation of development,’ which has multiple shades of meaning. It indicates a person’s situation with special emphasis on the subjective significance, especially the emotional and visceral impact of the situation on the person, recollection of which summons up the entire situation.”

Aaro Toomela also points out the difference between perezhivanie and opyt. He says, “The Russian words perezhivanije and opyt are both translated into English as experience. These two Russian terms, however, refer to psychologically very different phenomena. Perezhivanije is ‘unity of personality and environment . . . Perezhivanije must be understood as an internal relationship of a child as a human being toward this or that moment of reality’ (Vygotsky, 1984b, p. 382). Vygotsky, before becoming a psychologist, studied literature, art, and theater. Several central concepts he used, such as stage and category, can be understood only in the context of theater (Veresov, 2010). The concept perezhivanije belongs to this list; the complex meaning of the term should be related to Stanislavski’s system of training actors (cf. Vygotsky, 1984a). Opyt, in turn, refers to knowledge and skills that develop in the interaction with the environment.” (2014, p.102)

The concept of Perezhivanie aligns with ecological psychology’s rejection of mind-matter and subject-object dualism. For ecological psychologist James Gibson, the concept of Affordance “refers to both the environment and the animal in a way that no existing term does. It implies the complementarity of the animal and the environment” (Gibson, 1979, p. 119). Similarly, according to cultural-historical psychologist Lev Vygotsky, “…So, in a Perezhivanie, we are always dealing with an indivisible unity of personal characteristics and situational characteristics, which are represented in the Perezhivanie.” (Vygotsky, 1934, p. 342)

Nikolai Veresov emphasizes the concept of Perezhivanie is related to the principle of refraction. He explains, “What is important is that perezhivanie is a tool (concept) for analyzing the influence of sociocultural environment, not on the individual per se, but on the process of development of the individual. In other words, the environment determines the development of the individual through the individual’s perezhivanie of the environment (Vygotsky 1998, p. 294). This approach enlarges the developmental perspective as it introduces the principle of refraction. No particular aspects of the social environment in itself define the development, only aspects refracted through the child’s perezhivanie (Vygotsky 1994, pp.339–340). The perezhivanie of an individual is a kind of psychological prism, which determines the role and influence of the environment on development (Vygotsky 1994, p. 341). The developing individual is always a part of the social situation and the relation of the individual to the environment and the environment to the individual occurs through the perezhivanie of the individual (Vygotsky 1998, p. 294).” (2020)

According to Andy Blunden, “In The Problem of the Environment, Vygotsky illustrates the idea of perezhivanie by the case of three siblings coping or not with their single mother who is a drunk. The infant is indifferent to this situation, being too young to know; the middle child is traumatised; and the oldest child, a teenage boy, understands that he must become ‘the senior man’ in the family, makes an accelerated development and takes responsibility for looking after his siblings and his mother. That is, it is only the adolescent who is able to master the perezhivanie, and even in his case, without outside assistance, his own development may be damaged by his loss of childhood. In this way, Vygotsky showed how not just the social environment, but the significance of features of the environment for the subject and the subject’s capacity to process them, make up the essential units of analysis for understanding the development of the child.” This idea forms the core of Vygotsky’s concept of the Social Situation of Development. It also resonates with Gibson’s concept of Affordance, as both emphasize the interaction between environmental features and the subject’s capacity to engage with them.

The dialectical approach is the foundation of Vygotsky’s thinking. Nikolai Veresov highlights this by stating, “The principle of refraction shows dialectical relations between significant components of the social environment and developmental outcomes (changes in the structure of higher mental functions). This principle shows how the same social environment affects unique developmental trajectories of different individuals. Vygotsky’s famous example of three children from the same family shows that the same social environment, being differently refracted through perezhivanie of three different children, brought about three different developmental outcomes and individual developmental trajectories (Vygotsky 1994, pp. 339–340). In a certain sense, it would not be an exaggeration to say that the social environment as a source of development of the individual, exists only when the individual participates actively in this environment, by acting, interacting, interpreting, understanding, recreating and redesigning it. An individual’s perezhivanie makes the social situation into the social situation of development.” (2020)

1.5 Bronfenbrenner: Bioecological Systems Theory

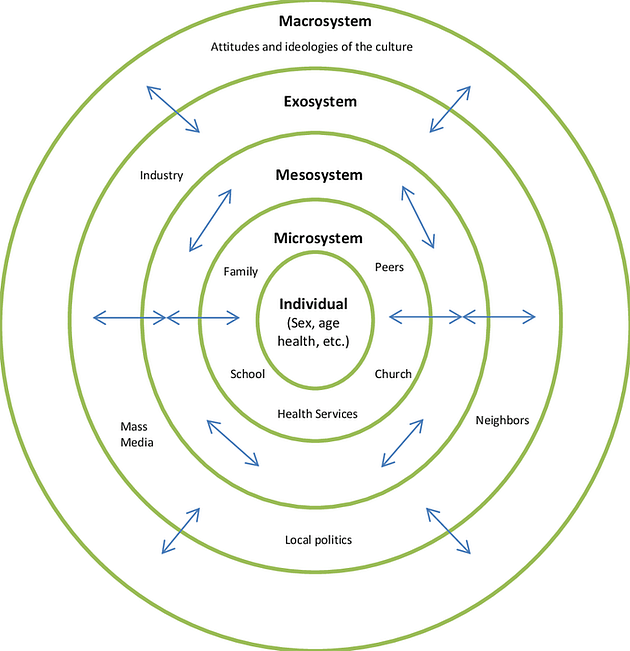

The final idea I want to highlight is Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Systems Theory, originally developed to explain child development. Bronfenbrenner’s model defines five interrelated layers of the developmental environment:

- Microsystem — The immediate environment surrounding an individual, including home, school, peers, and workplace.

- Mesosystem — The interactions between different microsystems. For example, the relationship between a parent’s workplace and their child’s school forms a mesosystem.

- Exosystem — A broader social system that indirectly influences the individual’s microsystem, even if the individual does not actively engage with it.

- Macrosystem — The overarching cultural values, ideologies, and laws that shape all other systems.

Bronfenbrenner also introduced the chronosystem, which accounts for the influence of time and historical events on an individual’s development. It is important to note that the typical diagram of his model does not explicitly depict the chronosystem as a separate layer.

Bronfenbrenner’s approach is highly relevant to the concept of the Developmental Platform. However, his model does not directly align with the concept. While it provides more layers than Self-Determination Theory (SDT)’s typology of social contexts, it remains challenging to pinpoint an ideal layer for the Developmental Platform.

- Could it be placed within the microsystem? Digital platforms such as Facebook and Twitter might fit here because they form part of our immediate environment, shaping daily interactions and engagements.

- Could it belong to the exosystem? This is also a possibility, as these platforms function as large social systems that exert an influence on users, even though individuals do not always have direct control over their structures or policies.

This raises an important question: How can a single entity be positioned within two different layers of the developmental environment? Digital platforms blur traditional boundaries between microsystem and exosystem, suggesting that the model may need further adaptation to account for hybrid environments where individuals both participate and are influenced at multiple systemic levels.

It seems we need a new framework not just for understanding traditional concepts such as home, school, workplace, and mass media but also for analyzing digital environments and other complex, dynamic, and developmental contexts.

Moreover, traditional developmental psychology primarily focuses on child development and emphasizes how individuals respond to existing social contexts. However, it does not sufficiently explore how people actively shape and create new contexts. This article addresses this gap by focusing on an adult’s creative life development, aiming to examine how individuals actively construct and transform their environments.

Part 2: The Ecological Practice Approach to Development

I have been developing the Ecological Practice Approach since March 2019, following the completion of my draft Curativity: The Ecological Approach to Curatorial Practice. This approach is inspired by James J. Gibson’s Ecological Psychology, Roger Barker’s Behavior Settings Theory, Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecology of Human Development, and various practice theories.

The Ecological Practice Approach is driven by two key goals:

- Expanding Ecological Psychology beyond its original focus on the natural environment to include the modern digital environment.

- Extending Ecological Psychology from a perception-centered psychological analysis to a social practice analysis.

Originally, development was not central to the goals of the Ecological Practice Approach. To integrate this perspective into the Platform-for-Development framework, I have begun aligning it more closely with developmental thinking. This section presents my insights on the theme of development.

Inspired by Lev Vygotsky and Urie Bronfenbrenner, I conceptualized “Development” as a dual transformation between “potential” and “actual”. A person’s development involves the transformation from the Potential Self to the Actual Self. This process is closely tied to the transformation between Supportance (potential) and Action (actual).

In the following section, I will first explore relevant ideas developed by Lev Vygotsky and Urie Bronfenbrenner, before moving on to present my own perspective. The discussion will use the concept of Developmental Platform — introduced in my 2021 book Platform for Development — as an example of my perspective on Development.

2.1 The Ecology of Human Development

Bronfenbrenner’s approach provides a solid theoretical foundation for the ecology of human development. According to Bronfenbrenner, “I offer a new theoretical perspective for research in human development. The perspective is new in its conception of the developing person, the environment, and especially the evolving interaction between the two. Thus, development is defined in this work as a lasting change in the way in which a person perceives and deals with his environment.”

The most important aspect of Bronfenbrenner’s approach is that it goes beyond the immediate setting. He emphasizes, “The ecological environment is conceived as a set of nested structures, each inside the next, like a set of Russian dolls. At the innermost level is the immediate setting containing the developing person.” Furthermore, he points out that what matters for behavior and development is the environment as it is perceived, rather than as it may exist in “objective” reality (1979, pp. 3–4).

Here, we can identify three principles that are also applicable to Developmental Platforms:

- Development is related to the relationship between a person and their environment.

- The developmental environment consists of nested structures, where the immediate setting is not the only layer.

- The perceived environment is more important than the objective environment.

I adopt these principles to expand the Ecological Practice Approach and use them as a foundation to guide the conceptualization of the structure of Developmental Platforms.

2.2 Self, Other, and Supportance

Inspired by James J. Gibson’s concept of Affordance, I developed the concept of Supportance, which refers to the potential action possibilities offered by the social environment.

So, what is Affordance? Let’s take a look at Gibson’s original definition:

“The affordances of the environment are what it offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, either for good or ill. The verb to afford is found in the dictionary, but the noun affordance is not. I have made it up. I mean by it something that refers to both the environment and the animal in a way that no existing term does. It implies the complementarity of the animal and the environment.” (Gibson, 1979, p.119)

The affordance concept describes the possibilities for action that the environment, including objects and other people, offers to a particular individual. The theory is multifaceted. According to ecological psychologist Edward S. Reed (1996), there are two ways of using the concept of affordances: concrete analysis and abstract analysis. The former illustrates how specific environmental properties can support particular species’ habits of life (e.g., how certain types of terrain support or hinder human locomotion). The latter focuses on how these particular relationships between an organism and its habitat are instances of ecological regularities or laws (p.40).

Inspired by the concept of affordance, I developed a new concept called Supportance for Platform Ecology in October. This concept is part of the broader conceptual framework of the Ecological Practice approach. The term Supportance is inspired by Gibson’s description of the following classic example of affordance:

If a terrestrial surface is nearly horizontal (instead of slanted), nearly flat (instead of convex or concave), and sufficiently extended (relative to the size of the animal) and if its substance is rigid (relative to the weight of the animal), then the surface affords support.

It is a surface of support, and we call it a substratum, ground, or floor. It is stand-on-able, permitting an upright posture for quadrupeds and bipeds. It is therefore walk-on-able and run-over-able. It is not sink-into-able like a surface of water or a swamp, that is, not for heavy terrestrial animals. Support for water bugs is different.

What Gibson described is an example of Supportive Affordance, which he uses as an exemplar of the concept of affordance. While Gibson’s concept of affordance applies to the natural environment, the concept of Supportance is specifically focused on the social environment. Since both Affordance and Supportance refer to potential action possibilities, I consider them as part of a potential hierarchical loop.

2.3 Potential, Actual, and Development

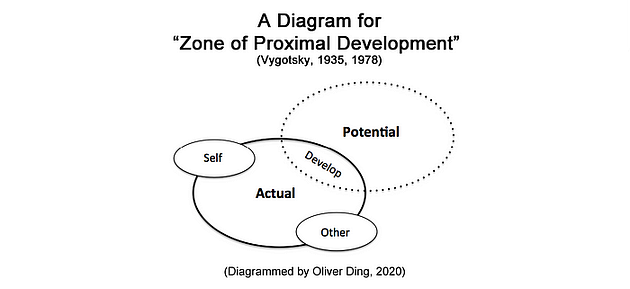

One key idea in Lev Vygotsky’s concept of the “ecological mind” is the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). This concept is defined as the space between actual development and potential development.

Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD): “…the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers.” (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 86, originally Vygotsky, 1935, p. 42)

Jaan Valsiner and Rene van der Veer share a story of the development of the ZPD in their article Encountering the Border. The authors use the term ZBR (zona blizhaishego razvitia), which is the original Russian term for ZPD. They point out: “Around 1931, Vygotsky had reached the theoretical necessity to conceptualize the ‘making of the future’ in human ontogeny (Zaretskii, 2007, 2008, 2009)… The earliest documented mention of ZBR can be found in a lecture in Moscow at the Epshtein Institute of Experimental Defectology on March 17, 1933. The third relevant presentation involving the introduction of the ZBR concept took place two months later — when Vygotsky gave a presentation on the development of everyday and ‘scientific’ concepts at the Leningrad Pedagogical Institute on May 20, 1933 (Vygotsky, 1933/1935e). Over this two-month period (March — May, 1933), Vygotsky began actively using the ZBR concept in various contexts. In all of these instances, the concept remained descriptive — marking an emphasis on the study of developing (as opposed to already developed) psychological functions. In the final fifteen months of his life, Vygotsky made numerous (though often passing) references to the ZBR concept. The surviving texts of Vygotsky provide us with a diverse collection of examples of his use of the ZBR concept.”

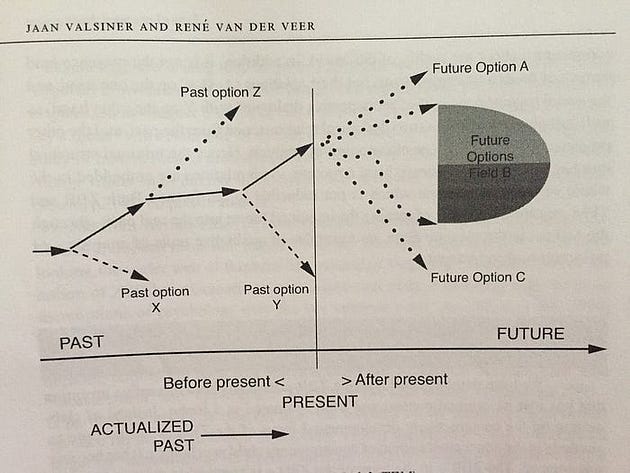

According to Jaan Valsiner and Rene van der Veer (2014), “the idea in ZBR — conceptualizing the processes of emergence of novelty in field terms — has had a recent parallel in the Trajectory Equifinality Model (TEM — Sato, 2009; Sato et al., 2007 2009, 2010, 2012). TEM grows out of the theoretical need of contemporary science to maintain two central features in its analytic scheme — time and (linked with it) the transformation of potentialities into actualities (realization).”

The above diagram represents the Trajectory Equifinality Model (TEM). What makes this model unique is that it incorporates both “real” (the actual developmental trajectory up to the present) and “ir-real” (possible trajectories that existed in the past and are assumed to exist in the future). Jaan Valsiner and Rene van der Veer explain, “TEM thus transcends the preponderance of psychology to include in its schemes only real phenomena, and treats reconstructions and imaginations as equal to the former.”

I view TEM as a general model of the “Actual — Potential” aspects of individual development. The diagram below generalizes the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). While the “Teacher-Student” relationship is replaced by “Self — Other,” the core dynamic of Actual — Develop — Potential remains the same.

From the above diagram, I define Development as the transformation between the potential self and the actual self through interactions with others. This idea aligns with the concept of Possible Selves, developed by Hazel Rose Markus and Paula Nurius.

In 1986, Markus and Nurius published a paper titled Possible Selves to challenge traditional theories of self-knowledge. According to them, “Possible selves represent individuals’ ideas of what they might become, what they would like to become, and what they are afraid of becoming. Thus, they provide a conceptual link between cognition and motivation. Possible selves are the cognitive components of hopes, fears, goals, and threats, and they give specific self-relevant form, meaning, organization, and direction to these dynamics. Possible selves are important, first, because they function as incentives for future behavior (i.e., they are selves to be approached or avoided), and second, because they provide an evaluative and interpretive context for the current view of self.”

Now, let’s consider the integration of self-development and its environment. Inspired by the above ZPD diagram, I’ve created a new diagram to visualize the relationship between Social Environment and Supportance.

The diagram above represents a new model of adult development from the perspective of the Ecological Practice approach. A person’s development refers to the transformation between the Potential Self and the Actual Self, and this process is linked to the transformation between Supportance (the potential action possibilities offered by the social environment) and Actual Action.

This model established a new theoretical foundation for adult development. In my 2021 book Platform for Development, the concept of the Developmental Platform was introduced as a special type of social environment.

In the next part, we will connect the Developmental Project and the Developmental Platform, building multiple units of analysis for the social environment.

Part 3: Developmental Projects and Beyond

Building on the previous discussion, this part connects Developmental Projects and Developmental Platforms, providing multiple units of analysis for social environments. Developmental Projects offer structured opportunities for personal growth, while Developmental Platforms highlight social formations that strongly support adult development.

A central theme is viewing Project and Platform as successive stages within an Enterprise. Projects may grow into Platforms, which in turn enable new Projects. From this perspective, social groups such as Organizations, Communities, Theory Schools, and Technological Platforms can be understood as outcomes of developmental projects, reflecting the accumulated patterns of human action within supportive environments.

3.1 The Concept of Developmental Project

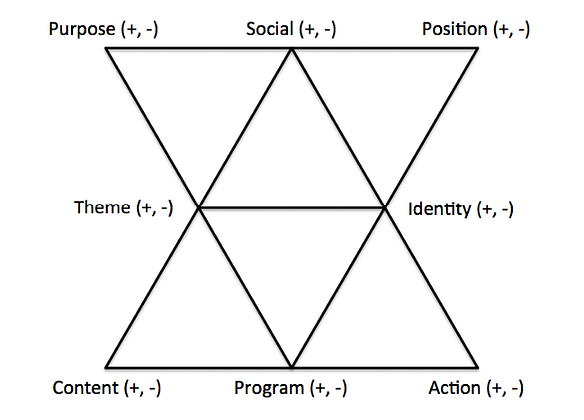

In 2021, the concept of Developmental Project was introduced to name the basic model of the Project Engagement Approach. See the diagram below.

The Developmental Project Model describes a project using eight interconnected elements:

- Purpose: Why do you want to initiate or join the project?

- Position: What’s the social structure of the project?

- Program: Does the project follow formal organizational processes?

- Social: How do you connect with others through your participation?

- Content: What new information and knowledge do you acquire by joining the project?

- Action: What concrete actions do you take in the project?

- Theme: Does the project introduce new and meaningful themes for your life development?

- Identity: How do you perceive your identity before and after joining the project?

The eight elements of the Developmental Project are grouped into three categories, representing a process of transformation:

- Situational Context: This group highlights three critical aspects of the Developmental Project: Purpose, Position, and Program.

- Developmental Resources: This group focuses on three types of potential opportunities for the Developmental Project: Social, Content, and Action.

- Impact by Projects: This group examines the personal development that arises from participation in a Developmental Project, viewed from two dimensions: Theme and Identity.

In this article, the concept of Developmental Project is detached from the Developmental Project Model and attached to an ecological approach to adult development.

It now refers to understanding the concept of “Project” from an adult-developmental perspective, serving as a new type of social environment.

It also connects to the concept of the Developmental Platform, the other special type of social environment.

3.2 The Concept of Developmental Platform

The concept of the Developmental Platform is defined as a social environment that strongly supports adult development in various ways. This definition is centered around three key terms:

- Social environment

- Strongly support

- Adult development

The term social environment is broad. It can refer to traditional social structures such as organizations and communities. Additionally, I consider digital platforms and other emerging social contexts as forms of social environments.

The term strongly support distinguishes between different types of social environments based on the degree of support they provide. While any social environment can offer some level of support, only a few can strongly support individuals. These highly supportive environments can be considered platforms.

The term adult development is well-established in developmental science. According to Wikipedia, “Adult development encompasses the changes that occur in the biological and psychological domains of human life from the end of adolescence until the end of one’s life. These changes may be gradual or rapid and can reflect positive, negative, or no change from previous levels of functioning.” Thus, the Developmental Platform concept is grounded in developmental science, emphasizing the role of social environments in fostering adult growth and transformation.

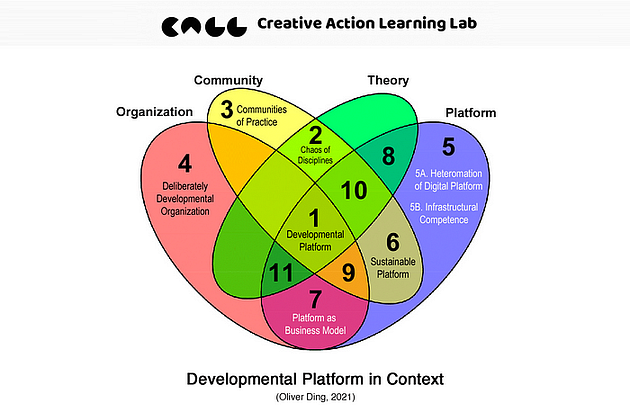

Do we need this new concept? To explore the necessity of the Developmental Platform concept, I used the following Venn diagram to identify its creative space. More details can be found in The Developmental Platform.

In general, I consider the Developmental Platform to be an intermediate concept — one that bridges theory and practice. It serves as a mediating framework for testing Supportance-based Development, providing a structured way to examine how social environments can strongly support adult development.

In practice, specific social groups such as Organizations, Communities, Theory Schools, and Technological Platforms can be understood as Developmental Platforms. In the following sections, we will build the connection between Developmental Project and Developmental Platform; in this approach, these social groups can be further understood as outcomes of developmental projects.

3.3 Project, Platform, and Development

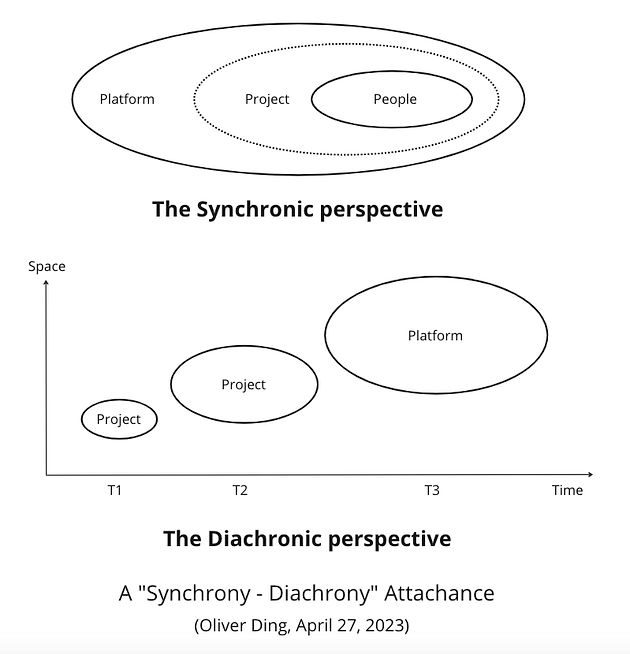

There are two ways to connect the concept of Developmental Project and Developmental Platform. See the diagram below.

The Synchronic perspective sees Project and Platform as two entities at the same time. In 2020, I moved from the ‘Project’ thematic space to ‘Platform’ thematic space and attached the concept of ‘Project’ to the Platform for Development framework.”

The Diachronic perspective sees Project and Platform as one entity at different times. In 2022, I moved back from the ‘Platform’ thematic space to the ‘Project’ thematic space. This time, I detached the concept of ‘Platform’ and ‘Platform Genidentity’ framework from the Platform Ecology approach and attached them to the Project Engagement approach (v2.0).

These two dimensions of the “Project — Platform” relationship were introduced in 2023 when I worked on the Mental Moves project. However, I did not further use it to revisit the concepts of “Developmental Project” and “Developmental Platform” from 2023 to October 2025.

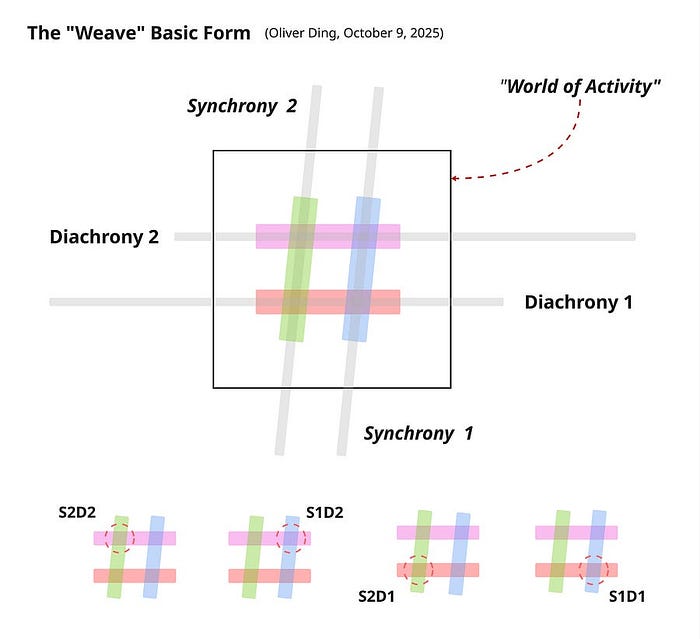

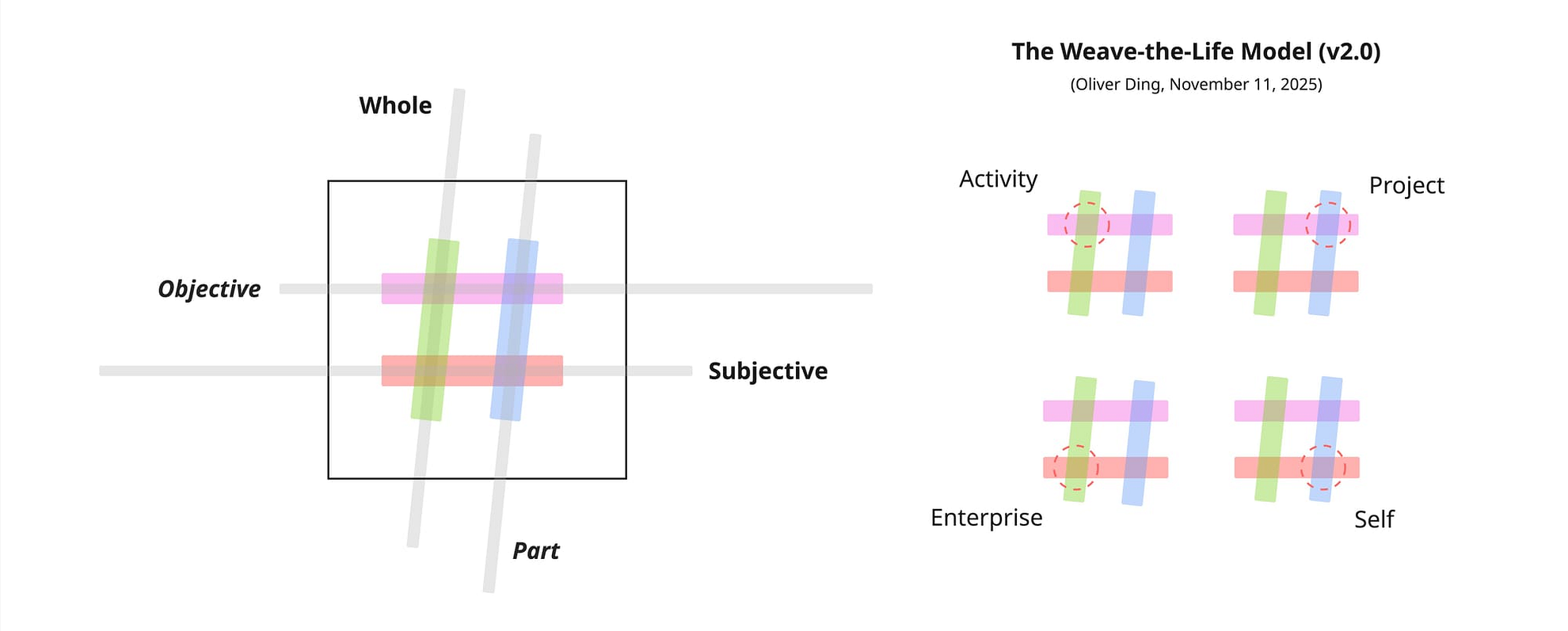

In October 2025, I officially introduced the “Weave” Basic Form, which combines two synchronic dimensions and two diachronic dimensions into one simple meta-diagram.

The model consists of four Weave-points (S1D1, S1D2, S2D1, S2D2), each representing a structural nexus where one synchrony dimension intersects with one diachrony dimension.

As an abstract model, the “Weave” basic form serves as the foundation for generating derived forms and situational frameworks, as illustrated in the examples above.

With the birth of “Weave” basic form, a new wave of theoretical development emerged in my creative journey from October to November 2025, which led me to incorporate the concept of “Enterprise” into the Project Engagement Approach.

In this framework, both Project and Platform can be understood as different stages within an Enterprise, where a Project may grow into a Platform, and Platforms provide a context for new Projects.

3.4 Activity, Enterprise, and Development

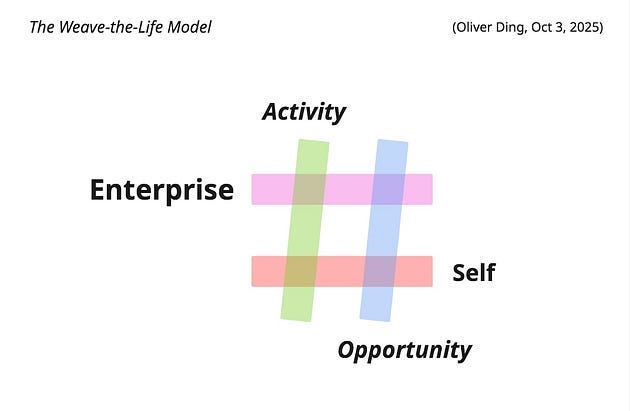

On October 3, 2025, I developed the Weave-the-Life model (V1.0), see diagram below.

The model draws a clear distinction between researchers and actors. While traditional Activity Theorists study Activity as an object of analysis from the researcher’s perspective, the concept of Enterprise re-centers the actor’s own perspective, giving the subjective experience back to them.

In the Weave-the-Life mode, we may picture an Enterprise as a chain — an ongoing sequence of endeavors that unfolds over time — while an Activity can be seen as a node within that chain, a self-contained system composed of coordinated actions.

This metaphor is meant as an illustration rather than a structural definition, highlighting how Enterprise emphasizes temporal unfolding (diachronic), whereas Activity emphasizes systemic organization at a given moment (synchronic).

Thus, while Activity Theory provides a structural snapshot of mediated action, the notion of Enterprise restores the temporal and experiential flow of human endeavor.

On November 11, 2025, I designed a new abstract diagram to represent the deep structure of the Weave-the-Life Framework. The new version was version 2.0.

The new model integrates four dimensions: Subjective, Objective, Part, and Whole. The Subjective–Objective dimensions capture diachronic aspects of life, while the Part–Whole dimensions capture synchronical aspects. Together, these dimensions weave individual and collective life within an evolving structural, cultural, and historical landscape.

The model defines four Weave-Points, where one synchronical dimension intersects with one diachronic dimension. Concepts from v1.0 are positioned at these points: Self, Enterprise, Project, and Activity.

- At the Part dimension, the Self–Project connection represents “Project Engagement,” where an individual participates in a specific project.

- At the Whole dimension, Activity refers to the aggregation of individual projects, while Enterprise encompasses a series of self-directed actions that extend beyond immediate projects.

The distinction between Subjective and Objective reflects the dual aspects of life: individual experience versus collective existence. The Part–Whole distinction reflects the structural depth of life. These four dimensions are continuously interwoven in lived experience, forming the fabric of both personal biography and social reality.

The framework operates bidirectionally. In the forward direction, individual actions crystallize into enterprises that transcend personal will. In the reverse direction, social structures and historical events enter individual life through activities and projects. This bidirectional dynamic illuminates both individual agency and structural constraints, demonstrating how otherness — aspects of social reality beyond immediate intersubjective negotiation — becomes incorporated into personal life.

By incorporating the concept of Enterprise, the Weave-the-Life Framework emphasizes the subjective dimension of social life: a long-term, self-determined trajectory of actions.

These basic ideas set a foundation for connecting Activity and Enterprise for the Project Engagement approach to human development because it offers a subjective perspective that the traditional approaches of Activity Theory did not emphasize.

3.5 The Development of Social Environment

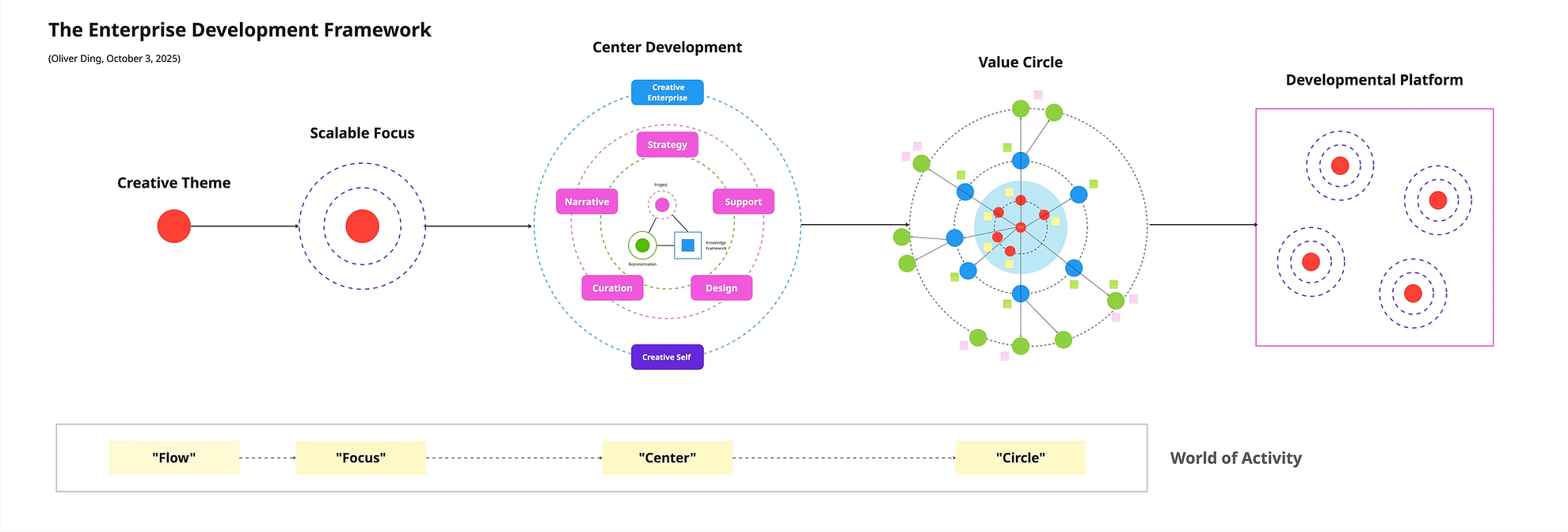

In October 2025, I also developed the Enterprise Development Framework for the World of Activity Approach. This framework provides structured guidance for managing and evolving a Creative Enterprise, integrating insights from multiple projects, and supporting the coordination of both thematic and identity-related aspects of development.

The diagram above illustrates the complete journey of enterprise development, highlighting five stages of an evolving enterprise.

- Creative Theme

- Scalable Focus

- Center Development

- Value Circle

- Developmental Platform

The “Developmental Project” concept is relevant at all five stages, guiding both project-level and enterprise-level development.

- Creative Theme: the pre-Project stage.

- Scalable Focus: joining or initiating a project with a scalable object.

- Center Development: developing a series of projects, turning the scalable object into a creative center

- Value Circle: connecting the center to other related centers, forming a network of projects

- Developmental Platform: the scaled center becomes a platform, supporting more projects to emerge

This model can be applied to diverse social environments:

- Family: a series of developmental projects around the “Love — Legacy” thematic schema

- School: a series of developmental projects around the “Teach— Learn” thematic schema

- Organization: a series of developmental projects around the “Collaboration — Achievement” thematic schema

- Community: a series of developmental projects around the “Connection — Exploration” thematic schema

- Market: a series of developmental projects around the “ Search— Change” thematic schema

- Technological Platform: a series of developmental projects around the “Affordance — Supportance” thematic schema

- City: a series of developmental projects around the “Local — Global” thematic schema

- Theory: a series of developmental projects around the “Theme — Concept” thematic schema

From the perspective of the Project Engagement approach, these eight types of social environments reveal a general pattern: every social formation can be understood as the outcome of a series of developmental projects organized around a distinctive double-theme schema. The specific relationship between the two themes in each schema — whether complementary, generative, or dynamic — remains open for further investigation.

This approach to differentiating social environments through their core thematic patterns echoes, in some ways, Niklas Luhmann’s method of distinguishing social systems through binary codes. However, whereas Luhmann’s codes operate at the level of communication systems (payment/non-payment for economy, legal/illegal for law), the double-theme schema operates at the level of developmental projects and human agency. This difference reflects a shift from systems theory to a project-oriented ecology: social environments are distinguished not merely by how they process information, but by what kinds of developmental projects they enable and organize.

This insight opens new directions for studying social development: not as abstract structural change or functional differentiation, but as the emergent product of developmental projects, reflecting the accumulated patterns of human action and thematic engagement within their environments.

Conclusion: Toward a Project-Oriented Ecology of Adult Development

This article presents a novel approach to adult development by situating Developmental Projects and Developmental Platforms within a dynamic social-ecological framework. Integrating classic developmental theories with new concepts such as Enterprise, the Weave-the-Life model, and double-theme schemas, it shows how individual actions and supportive social environments co-construct long-term growth.

From a synchronic perspective, social groups serve as developmental environments that provide the foundation for individuals to engage in meaningful Developmental Projects. From a diachronic perspective, the accumulation and evolution of these projects generate diverse social groups, and even Developmental Platforms, which in turn support new projects, creating an ongoing cycle of personal and collective development.

While the Enterprise Development framework, the Weave-the-Life model, and the double-theme schemas offer a promising operational toolkit to connect individual experience with social environments, further empirical testing and application remain needed.

Version 1.0 - November 29, 2025 - 8,834 words